I am not sure, but I think I may have been a theistic personalist for most of my active ministry. “Egads,” you say. “Yes,” I reply, “I’m afraid so.” “But what is a theistic personalist?” “Someone who espouses theistic personalism, of course.” “And now you are going to tell me what it is, right?” “My pleasure.”

I am not sure, but I think I may have been a theistic personalist for most of my active ministry. “Egads,” you say. “Yes,” I reply, “I’m afraid so.” “But what is a theistic personalist?” “Someone who espouses theistic personalism, of course.” “And now you are going to tell me what it is, right?” “My pleasure.”

According to Brian Davies theistic personalism makes person the decisive philosophical category for thinking about God (An Introduction to the Philosophy of Religion, pp. 9-15). We all know what human persons are. For good or ill, we have to live with them every day. So what do we mean by the word? I don’t know what the philosophers would say, but let me throw out this tentative definition—a person is a center of consciousness with whom we can rationally converse. This is probably severely defective, but at least it will get us started.

Now let’s turn to the Bible and its rendering of deity. Doesn’t YHWH sound and act like a person, not in the sense that we can physically see him, but in all the other important ways that constitute personhood? Consider the definition of God advanced by one of the world’s premier Christian philosophers:

By a theist I understand a man who believes that there is a God. By a ‘God’ he understands something like a ‘person without a body (i.e. a spirit) who is eternal, free, able to do anything, knows everything, is perfectly good, is the proper object of human worship and obedience, the creator and sustainer of the universe’ (Richard Swinburne, The Coherence of Theism [rev. ed.], p. 1).

God is that person, Swinburne says, who is “picked out by this description” (The Existence of God [rev. ed.], p. 8).

If Swinburne’s exposition represents theistic personalism, then this is pretty much what I preached and taught throughout most of my parochial ministry. I suspect that theistic personalism is the default position of the overwhelming majority of Protestant preachers and probably a fair number of Catholic and Orthodox preachers. It begins where all preachers begin, namely, with the Scriptures. We preach the God of the Bible—the Holy One who spoke to Abraham and commanded him to leave his home and journey to Canaan, who delivered his people from slavery in Egypt, who gave the Torah to Moses on Mt Horeb, who spoke to Israel through the prophets, who sent his beloved Son in the fullness of time to die for the sins of humanity and rise into indestructible life. Once God is introduced as a character in a narrative, then of course he will and must be portrayed as a being, a divine self, analogous to a human self. How else could a story be told about him? This means that if we take the Bible straight, as it were, we will always think of God as person. All we then need to do is detach God from embodiment and finitude, and … voila! … we have Swinburne’s omnipresent spirit.

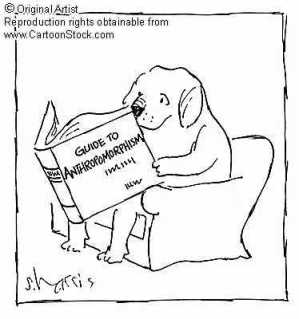

Edward Feser has criticized theistic personalism as inescapably anthropomorphic and contrasts it with the classical Christian understanding of divinity:

Theistic personalists, by contrast, tend to begin with the idea that God is “a person” just as we are persons, only without our corporeal and other limitations. Like us, he has attributes like power, knowledge, and moral goodness; unlike us, he has these features to the maximum possible degree. The theistic personalist thus arrives at an essentially anthropomorphic conception of God. To be sure, the anthropomorphism is not the crude sort operative in traditional stories about the gods of the various pagan pantheons. The theistic personalist does not think of God as having a corporeal nature, but instead perhaps along the lines of something like an infinite Cartesian res cogitans. Nor do classical theists deny that God is personal in the sense of having the key personal attributes of intellect and will. However, classical theists would deny that God stands alongside us in the genus “person.” He is not “a person” alongside other persons any more than he is “a being” alongside other beings. He is not an instance of any kind, the way we are instances of a kind. He does not “have” intellect and will, as we do, but rather just is infinite intellect and will. He is not “a person,” not because he is less than a person but because he is more than merely a person. (Also see Feser’s article “Classical theism.”)

The emergence of theistic personalism has made it possible for theologians and philosophers to begin to significantly redefine the attributes of God. The first to go were immutability and impassibility. After all, don’t the biblical writers speak of God as changing his mind, repenting of his actions, and experiencing grief, anger, and joy? More recently, open theists have begun telling us that the divine omniscience is limited—God does not exhaustively foreknow the future. A significant revision of the traditional understanding of divinity is now taking place in some Christian quarters. When one reads a philosopher like Swinburne, one hardly notices the shift in emphasis; but the shift becomes marked when one reads those who are more fearless about departing from inherited formulations.

David B. Hart has devoted a few pages of his recently published book The Experience of God criticizing this new, or at least different, model of deity. Hart is blunt. Advocates of theistic personalism (he prefers the term “monopolytheism”) have broken with the catholic tradition. They are advancing, he writes, “a view of God not conspicuously different from the polytheistic picture of the gods as merely very powerful discrete entities who possess a variety of distinct attributes that lesser entities also possess, if in smaller measure; it differs from polytheism, as far as I can tell, solely in that it posits the existence of only one such being” (p. 127).

There’s a serious problem here. I did not begin to recognize the problem until I discovered the writings of Herbert McCabe a decade ago and began to re-assess my theology—but still I minimized it. But then I began worshipping the Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom. Apophatic theology became not just a way of doing theology but a reality lived and prayed. I find it difficult to articulate in words how this is so; it is the experience of the whole: the chanting, the icons, the candles, the incense, the multiple invocations of the Trinity, the opening and closing of the Royal Doors, the sacred choreography, the Anaphora and Epiclesis, the Communion—together they manifest the subtle interplay of negative and cataphatic theology.

It is proper and right to sing to You, bless You, praise You, thank You and worship You in all places of Your dominion; for You are God ineffable, beyond comprehension, invisible, beyond understanding, existing forever and always the same; You and Your only begotten Son and Your Holy Spirit. You brought us into being out of nothing, and when we fell, You raised us up again. You did not cease doing everything until You led us to heaven and granted us Your kingdom to come. For all these things we thank You and Your only begotten Son and Your Holy Spirit; for all things that we know and do not know, for blessings seen and unseen that have been bestowed upon us. We also thank You for this liturgy which You are pleased to accept from our hands, even though You are surrounded by thousands of Archangels and tens of thousands of Angels, by the Cherubim and Seraphim, six-winged, many-eyed, soaring with their wings.

“We have entered the Eschaton, and we are now standing beyond time and space,” exclaims Alexander Schmemann.

Philosophy must give way to the Mystery.

Yes. Good explanation here. I love the video clip.

Re: the video. The size of that Chalice alone is formidable! This does seem a fitting, albeit ultimately inadequate, symbol for the uncontainable Mystery contained within it–one that is not only awe inspiring in its majesty, but also incomprehensible and unspeakable in the fullness of its Truth.

LikeLike

Karen, yes! That large chalice is a wondrous symbol “the uncontainable Mystery contained within it.” Beautifully put.

LikeLike

Father Bless

When I read the line “More recently, open theists have begun telling us that the divine omniscience is limited” I had immediately recalled a line from a prayer I often use. “Let us not be caught in the tyranny of our rational minds, which create “innovations” on the faith, which lead us to hold prideful “theologies” that diminish God to the level of our understanding, or worse, deny Him altogether.” I am not saying that we should not study God, yet approach the subject with fear and trembling, never forgetting that I am in the process of becoming healed, and that what I say may be a stumbling block to others. To limit God in any way shape or form in my opinion is a dangerous path to tread, and not just for me, for those that I share with.

LikeLike

Profoundly yes. It will sound perhaps strange to say this, but without apophaticism I probably would not (could not) be a believer. Theistic personalism, by whatever name, ceased to make sense (believable sense) long ago. In some ways, it made too much sense. The “God of my understanding,” just isn’t God. As to person, I have greatly appreciated and recommend Elder Sophrony. He pushes the envelope on person in a very good manner. But he doesn’t bring personhood as something he knows and apply it to God. Rather God makes known the meaning of personhood. And, frankly, even that is pretty elusive. When I first approached all of this it felt like someone had taken the floor out from under me – except that I realized the floor was not legitimate as a place to stand. Thanks for the series.

LikeLike

Pingback: Theistic personalism vs. classical theism, revisited | A Thinking Reed

Pingback: Amended comment at @thinking_reed’s blog on theistic Personalism v classical theism » CK MacLeod's

I’m loving this series. I’m a recent convert to Orthodoxy and have been reading Hart’s new book as well. Yet I’m trained as an analytic philosopher, and almost all the big name analytic philosophers of religion are theistic personalists. So the conversion to classical theism has been a struggle, but an exciting one.

LikeLike

Back in the 90s I read a fair amount by Richard Swinburne and William Alston. I learned a great deal from them (most of now forgotten, sadly, especially with regards to literal and metaphorical speech. Last night I picked up my old copy of Alston’s book on religious language. I have to confess that it doesn’t impress me in the way that it did back then. It seems to me that a critical religious dimension is overlooked in all of Alston’s finely-tuned philosophical argumentation.

A book I ordered through ILL arrived last week–The Trinity: East/West Dialogue. I was intrigued by the book because it contains papers given at a conference attended by analytic philosophers and Russian Orthodox theologians. I am disappointed in the papers on the Trinity delivered by the philosophers. It’s as if the doctrine of the Trinity is an intellectual conundrum to be solved rather than a wondrous mystery to be lived and prayed. I can imagine the Russian theologians just shaking their heads and muttering to themselves, “These Latin scholastics just don’t understand …”

Jeremiah, please do read Hart’s new book and let me know what you think.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Orthodox Ruminations.

LikeLike

All of the various branches of the so called great religions that are aligned with centres of political power are armed to the teeth. This is especially so within the sphere of Christianity and Islam.

Indeed what are now promoted as the so called great religions are only the most superficial and factional and often dim-minded and perverse expressions of ancient power-and-control-seeking national and tribal cultism.

All God-ideas whether single or plural, or feminine or masculine in their descriptive gender are creations/projections of the entirely dualistic individual or collective ego that make them.

Can a sinner, who by self-definition and always dramatized action is turned away from the Living Divine Reality, and thus entirely God-less, say anything meaningful about the Living Divine Reality? Or are all of his/her speculations merely a projection of his/her sinfulness?

All God-ideas are created by the mind(s) of sinful ego’s. And all God-ideas not only reflect the sinful ego itself, but, altogether, God-ideas, being MERE ideas, reinforce and console the state of sinfulness,and, in fact, subordinate the Living Divine Reality to the sinful ego’s search and purposes (in both its individual and collective forms).

The Living Divine Reality is thus reduced to the mortal human scale only, and thus effectively makes the Living Divine Reality the slave of the sinful collective. The enslaved Divine is then used to justify all of the inevitable atrocities that sinful collectives always dramatize on to the world stage.

LikeLike

It’s easy for a Christian trying to conjure a rational theology to dismiss a lot of the Old Testament stories. It’s no great loss to most Christians’ religious belief if Yahweh didn’t literally speak from a burning bush, command Abraham to kill Isaac, or send an angel to wrestle Joseph. But…

The problem in trying to get rid of all the anthropomorphic aspects is that, in the end, it gets rid of Christianity. Does your non-personal god love us? Does “he” want us to believe in certain ways and not others? Does “he” have any desire for us? Did he incarnate himself into the person of Jesus? And if so, why? This is where the theologian trying to have it both ways waves his hands and repeatedly speaks of mysteries.

There is no mystery here. Any meaningful explanation of why people should care about or want a relationship with the Christian god inevitably requires him to be cast as a person. Even if believers don’t need the god of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, they need someone. In contrast, the God that isn’t merely a god but the “ground of all being” has about as much personal importance to most people as the physicist’s dreamed-for Theory of Everything. (Indeed, it’s not clear they’re any different.) You can avoid the problems of believing in a god by saying you believe only in “God,” the unknowable ur- that even physicists and atheists can’t dismiss. But where the atheist then will trip you up is by pointing out that there is zero reason to connect that with anything resembling Christian belief and practice. The moment you try to connect the two, we will point out that that the object of your speech is no longer that unknowable ur-, but once again, a god.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you are correct about this. I surmise that the mystery of God’s person is not less personal than persons as we recognize them in human beings, but more so. The Trinity is the fully real nature of Personhood. Our own personhood and that of those we know and love is personhood on the way, as it were. Christos Yannaras is worth reading on this issue.

LikeLike

Certainly. I agree with everything you have said. This is nothing new though. I was reading N.T. Wright’s book the other day and what I struck me was when he talked about the religion of the Stoic, Epictetus. He could to pray to Zeus, Father of All, the one minute and preach all the gods were the same the next. The Egyptian higher-ups could say Amon-Re was the One Ennead in himself, and the people worshipped a whole plethora of gods.

With regards to Jews and Christians, at least, this is nothing new either. On the one hand, YHWH could not be represented adequately by anything and was proclaimed to be “One,” unique, ultimate, eternal, and in a category by Himself as Creator absolutely separate in form from gods, angels, and creatures. He was omnipresent in some capacity at least in some circles and could not be contained in the heavens themselves, much less the earth or a temple. Yet there is He walking in the Garden, talking with Abram on the plains, etc. Even prior to the Exile, this role was assumed by the Angel of YHWH/Yahoel, Wisdom, the Name, the Glory, the Divine Extent/Shiur Qoma just to solve this problem – a circumlocution for God so that He, the one who no one has seen but the Son, remained in the “heavens,” a precursor to the Word of St. John. In Jewish Kabbalah, it is expressed as the distinction between Ein Sof and the Heavenly Man. In Orthodox Christianity, this same bridge is the Essence-Energy distinction. Of course, Plato had devised his Demiurge which Philo synthesized with an already secondary divine figure within Jewish scriptures – a track followed by St. Justin Martyr.

I might venture to say that God acquires Personhood only in the perpetual reflection of the Trinity – the gaze of God upon Himself in the Word/the Name from which things “boil over,” as Eriugena and Eckhart would put it. Both Jewish and Christian “mystical” (as much as that word is bandied around) traditions talk about the efficacy of prayer and sacrifices which invoke the Word of God who is at once mediator-priest and God. Between the lines of the Old Testament is the idea that the covenants are bound in God’s Name which makes them effectual, binds them like in the “Deep Magic” of Lewis’ Chronicles. I would recommend Fr. Murray’s “Cosmic Covenant” book for this. If I may say, these things seem participation in that speaking of God to Himself, that reflection, that offering back from the Word to God. That is why it was said that High Priest Simon the Righteous once said that the world was upheld by three things – the Torah, the Temple sacrifices, and acts of loving-kindness. Ironically enough, though I don’t think he knew of Simon, Padre Pio, if I may cite him, said that the world could exist more easily without the sun than the Holy Mass. Somehow, this is all one creative act subsumed into the uncreated Trinity. I’m not certain how I got on this tangent, but I suppose I am trying to explain one possible vision of how prayer and human acts in time might relate to the eternal life of God. One image I particularly like for this is Scotus’s where the Incarnation is the subsumption of the world’s highest offering, rational Man who is himself an offering of the nonrational creation as its highest gift before its representation back to God through the Incarnate Word.

LikeLike

Particularly, it might make more sense to ask what creation might seem like from the perspective of the Trinitarian God, from within that eternal act if it’s possible, to alleviate the problem. At the same time, it’s natural to maintain our perspective and, from “outside” this system, personalize God only insofar as the Word reveals itself.

LikeLike

Perhaps a clarification is in order. In criticizing theistic personalism I am certainly not asserting an impersonal deity nor denying that God of the Christian faith is personal, though we would certainly need to unpack what this might mean. The critical point, I think, is to recognize that we cannot import into the deity our creaturely construals of personhood or personality, for God surpasses, transcends, and negates all of our creaturely categories. He is not an inhabitant of the universe: he is the one who has freely brought the universe into being from out of nothing. Hence the importance, IMHO, of beginning our reflections with the divine transcendence, i.e., God’s radical difference; otherwise, we will find ourselves falling into idolatrous thinking and speech.

Personhood has been a been an important theme in modern Orthodox theology—Zizioulas, Yannaras, and Sophrony immediately come to mind. But as Zizioulas would be the first to remind us, when we are talking about God we need to be sure that we not project into God our psychological understandings of what it means to be a person. Otherwise we will end up thinking of the three hypostases as three centers of consciousness, which is tritheism. Zizioulas precisely criticizes Staniloae along these lines: “the Cappadocain and Greek patristic view of personhood … in fact excludes an understanding of the person in terms of subjectivity” (Communion & Otherness, p. 134, n. 64). Well, I don’t know about anyone else, but when I think of “person” I immediately think of subjectivity, and I suspect I’m not alone.

For an example on why this is important, read through Dale Tuggy’s article on the Trinity in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Consider this passage:

Tuggy clearly falls into the classification of a theistic personalist, and he rejects the orthodox understanding of the Trinity because, in his view, it inevitably leads to tritheism or modalism.

But where all of this really hits the road is in Christianity’s debate with atheism. I cannot too strongly recommend David B. Hart’s The Experience of God.

LikeLike

“In criticizing theistic personalism I am certainly not asserting an impersonal deity nor denying that God of the Christian faith is personal, though we would certainly need to unpack what this might mean. The critical point, I think, is to recognize that we cannot import into the deity our creaturely construals of personhood or personality…”

In which case, you never will be able to unpack what it means for your god to be personal. Doing so requires some construal. By yourself, a human. (And if you can’t unpack it, then that quality of being “personal” has no importance or meaning to us. And no relationship with what we usually think of as personal. It becomes just another word that has been borrowed for its appeal.)

So you’re skewered by the horns of the philosophical dilemma you have made yourself. You can indeed save your god from a lot of traditional criticism by shifting to belief in G-D, by definition beyond all the particular claims on which such criticism is based.

You undo that, when you claim he is a personal god. For that to have any meaning at all, it has to be something we humans can construe.

You can have a personal god who loves us, who desires a personal relationship with us, who is morally perfect, who sent his son to live as a human. That is a god. That god differs in particulars from Odin and Zeus. But still has a broad range of characteristics, which characteristics motivate belief, practice, and ritual, and which characteristics also provide hooks for philosophical discussion.

Or, you can have G-D, abstract and unknowable, the philosophic “ground of all being.”

The problem is that these are not the same. To the extent that we can make sense of the “ground of all being,” there is no sense in which it can love humans or by which we can have a personal relationship with it. The moment you start describing G-D in a way that would make it look more like the Christian god, you’re undoing the philosophical move you made when saying, “no, no, not a god, but G-D.” The only way you can preserve that move is to avoid trying to give it the characteristics that would make it a god. In particular, the Christian god. If it really is G-D in which you believe, it is the same G-D that some Buddhists claim, and the same ontological notion that physicists and philosophers can discuss. And there is little point in praying to it or worshiping it, except as some meditative exercise.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have to disagree with you, Russell. The Christian Church does not need and has never needed a rational account of the personhood of God in order to justify its praxis. From the beginning Christians have invoked, worshipped, obeyed and served the Holy Trinity, while at the same time affirming his absolute incomprehensibility and ineffability.

We call God “personal” not because we know what this means for God but because it is absurd to say that God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob is impersonal. But once we have affirmed that God is personal, dangers remain, as noted by McCabe:

The apophaticism of, say, St Gregory the Theologian or St Thomas Aquinas simply does not lead to the dire consequences that you foresee, Russell. We are still praying to the Father. We are still serving our Lord Jesus Christ. We are still invoking the Spirit. And we are still attributing to God properties like love and goodness and wisdom. Different theologians have offered various theories on how we can do this and still affirm God is incomprehensible Mystery, but nothing hinges on figuring out all of this precisely and infallibly.

LikeLike

Well, Hart’s book is indeed a corrective to talk about God that gets stuck at the ontic level of things. Certainly, his critique of secular rationalism and the fideistic fundamentalism that it engenders is devastating. If one follows his argument with perspicacity, it is clear that the gods of paganism are elements of the world and not a Creator God. One can, of course, group the Biblical God with pagan divinities, but this is a category error.

Apophatic theology is a recognition of the limitations of all our conceptual efforts at grasping God. However, it is wrong to say that philosophy can only properly speak about an impersonal ground of being that is the same for Buddhists, monotheists, etc. This falsely limits what the mind can actually know and reflect upon. All symbolic and metaphoric knowledge relies upon an originary astonishment about being. The question is, does this astonishment have a trajectory? Can we move beyond a kind of wordless acknowledgement of wonder to any kind of language? One of the key ideas in Christian theology — and one can discover it’s possibility in Plato — is the analogy of being. In this view, all of reality bears a meaning that is larger than any particular grasp that we can hold. The modern West rejects all this. It mainly opts for a positivist, nominalist, univocal concept of being. For us, the real is that which can be captured by quantifiable, experimental data. We tend to allow for equivocation, but that is relegated to the realm of subjective imagination. If one rejects both of these as comprehensive of reality, one might retreat to a purely negative aconceptuality.

This is not the only possibility, however. I could say something here about dialectic and German idealism, but that would be even more abstruse — the chief thing is that one can argue for a symbolic metaphysics in which beings, in all their unique, historical unrepeatability and the dramatic interaction between beings is always already a reality that is gifted by the ground of being. In this sense, the Source is never simply a No-thing that transcends our concepts, but a No-thing that speaks through being, whose creation can meaningfully point towards a Creator that one can truly talk about, though never comprehensively grasp. It was a medieval axiom, btw, that if you can comprehend it, it is not God.

In any event, I reject the notion that as a philosopher, one is compelled to a minimalist notion of G-D, if you will. A good philosopher to read on some of this is William Desmond.

LikeLike

brian writes: “the chief thing is that one can argue for a symbolic metaphysics in which beings, in all their unique, historical unrepeatability and the dramatic interaction between beings is always already a reality that is gifted by the ground of being. In this sense, the Source is never simply a No-thing that transcends our concepts, but a No-thing that speaks through being.”

I don’t know what you mean by “gift” or “speak” in the sentence above, only that they cannot mean what those words usually mean, both requiring an actor with intentionality, and that being part of what gets left behind in moving from a personal god.

Apophatic theology seems to me largely a rhetorical trick. It first denies that we can say anything about G-D, because our human concepts can’t apply. And then tries to bring back in all these words it wants to apply to G-D, to re-create a god that is appropriate to the Christian religion. Words like “give,” “speak,” “love,” etc.

Someone who gives and speaks need not be human or mortal. But must be a person in some sense, and an object that can be referenced by language. Otherwise, why are you using those words, when your intended meaning for them — if any! — has no connection to how they otherwise are understood?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Russell, as you are aware, it is easy to bring up objections — almost effortless — which would entail considerable space and time to address. In this kind of venue, one must try to suggest, rather than work out a developed argument. There are differing metaphysics, differing notions of how language works. In some, language about God is not non-sense — though God is surely the oddest word — a way of denoting a radical transcendence that is also an ontological intimacy. Holderlin says “the god is near, but hard to grasp.” I would add “so near as to appear absent.”

If one comes at this from analytic philosophy or positivism or any number of possible starting points, one may very well conclude that talk of gift and speech is illicit. I think those starting points are narrow and ultimately tone deaf to the music of being, but it is hard to argue with such. Herakleitos talked of contradiction in one of his enigmatic aphorisms as indicative of an antinomic quality in reality — what is needed is a form of paradoxical cognition that evades a certain blunt common sense and logic. Language is simpler and more linear in rationalities that reject this mode of knowledge (Descartes’ clear and simple ideas come to mind,) though it is more accurate to say that these circumscribed and usually instrumentalized forms of reason lack the capacity to recognize their lack. The apophatic is not a univocal concept, btw, but all of them share a desire to be just to what Herakleitos’ insight remarks. It is certainly not a mere trick of rhetoric, but it could appear so if one has not had the kind of experience that provoked the insight.

Anyway, if you are at ll artistic or sensitive to beauty at least, you might consider how the experience of beauty overtakes our attempts at autonomy and intentional command. There is something similar in the experience of inspiration. These are examples where the meeting of being and the good are existentially present to us. In these moments, there is a natural gratitude for being. This is an experience of gift that could imply a giver, though this is just an analogy. A truly worked out metaphysics of gift is more complex.

LikeLike

Pingback: God as musician; “classical theism” | bone wood & stone

Reblogged this on Theologians, Inc. and commented:

Seems to be a hot topic in the theoblogging world.

LikeLike

Hi friends,

I’m an open theist who is particularly drawn to Orthodoxy. I thought as an open theist I’d contribute a comment on the standard open view understanding of omniscience (which is often mistaken by non-open theists). And I thought as somebody very interested in Orthodoxy who is trying to bring his open theism into conversation with his love for much about Orthodoxy, I might try to put in a good word not for ‘theistic personalism’ as characterized here but for the values that I think are behind a LOT of what you all would call theistic personalism.

First, open theists don’t limit the divine omniscience or deny that God’s (fore)knowledge is perfect, infallible, and exhaustive. And we don’t have to tweak or change the definition of the concept of omniscience to argue this is so. Omniscience isn’t a very difficult or complex idea to grasp. If it means (to open a can of worms) ‘knowledge of all truths’, or more specifically ‘all truths about the future’, then open theists have no problems affirming that God is omniscient. For us the question is, What is true about a future which is not (as the Orthodox agree) exhaustively determined and fixed by God but open to being shaped and determined by creatures? Like I said—can of worms. But I just wanted to go on record as objecting to the characterization of open theism as ‘limiting’ God’s knowledge or denying his knowledge of all truths.

Second, I’m all for apophatically qualifying the sense in which we describe God as ‘personal’ or ‘three persons’ or as possessing those capacities typically thought to characterize personal being (like thinking, choosing, responding, relating, etc.)—though we have no idea ‘how’ these obtain in God’s case. But we also have to equally qualify the denials that God is or has these things.

Is there a view out there which sees God as merely a human writ large? Yes. Do they defend their view by tapping into resources like the philosophical view of ‘personalism’ or other disciplines? Sure. But tread softly. There are some good points to be made here. Denys Turner (no friend of open theism and a huge proponent of apophatic theology), building on Pseudo-Denys, insists that God is more like a plant than a rock, more like an animal than a plant, more like a chimp than an ant, more like a man than a chimp…and more like…no, that’s it. It stops with humankind as divine image bearers. Even if with each rung in the ladder we are affirming and denying as we ascend, it seems to me the personalists make at least this valid point (and I’ll find Hart’s repeating the same point in Beauty of the Infinite): ‘Person’ remains the highest category under which we can conceive of God. Granted, our conceiving is done within the constraints of created being and the cataphatic which are transcended by God. But without having to ‘reduce God as personal to what it means for humans to be personal’ (which it seems is the sort of ‘personalism’ being objected to here), it can nevertheless be the case that our experience of personal existence be read as God revealing himself within the created order (certainly an Orthodox thought) and not as us uploading creation into God.

If, as Denys says, apophaticism is only properly embraced on the other side of exhausting the cataphatic (which demands that we speak as much as possible, say as much as possible, etc.), then let’s be careful not to foreclose upon a proper apophaticism by condemning this or that aspect of the cataphatic. And it seems to me that describing God in personal terms is a function of the cataphatic. We ought to exhaust such language in God’s case, not forbid it—and I do ‘sense’ (could be wrong) that there’s a bit of reluctance to access personalist ‘language’ in God’s case just to avoid the wrong associations. That would be a huge mistake.

I guess what I’m saying is, if the theistic personalists aren’t employing the cataphatic rightly, why not show them how? Just saying, “Hey, don’t say that. It’s not Orthodox. God’s transcendent!” might not be very helpful. I get wanting to avoid taking all our creaturely experiences of what being ‘personal’ means and simply uploading them into God (minus the imperfections). But with that caution in hand, show me how to do it.

LikeLike

“For us the question is, What is true about a future which is not (as the Orthodox agree) exhaustively determined and fixed by God but open to being shaped and determined by creatures? Like I said—can of worms. But I just wanted to go on record as objecting to the characterization of open theism as ‘limiting’ God’s knowledge or denying his knowledge of all truths.”

Tom, do you believe that classical theists in either the Catholic or Orthodox Churches assert that the the future is “exhaustively determined and fixed by God but open to being shaped and determined by creatures”? If not, then who are you and your fellow open theists arguing against? If classical theism does not necessarily entail that which you most fear, then why identify oneself as an “open theist”? Or could it be that many open theists in fact are formulating their theology outside the classical framework?

LikeLike

Good question Fr Aidan. The Orthodox of course do not think God knows the future because he determines it (in Augustinian or later Calvinist fashion). If I’m right, the Orthodox agree we shape outcomes freely through our choices (choices ‘we’ determine). There’s agreement then between us on this. Beyond this agreement it’s just a matter of carrying through the implication consistently. That’s what my question was trying to get at. We can agree that our choices shape the future in ways God does not determine (contra Augustine and Calvin), but whether believing this is also compatible with believing everything about the future is eternally and timelessly known is a different question. One (incoherent, I think) example of how uncomfortable the Orthodox understanding is applied (e.g., the providential use of foreknowledge) would be Gregory of Nyssa’s work On Infants’ Early Deaths. [http://anopenorthodoxy.wordpress.com/category/foreknowledge/].

LikeLike

For example, Fr Stephen says Elder Sophrony “doesn’t bring personhood as something he knows and apply it to God. Rather, God makes known the meaning of personhood.” I would not say no to this at all. But I’m very interested to know where and when and how God makes known the meaning of personhood so I can see and understand it.

LikeLike

Hi Father,

First, I’d like to congratulate you on your series on God. As someone with a Ph.D. in philosophy, I really admire your clarity of communication. I just wish I could write as elegantly as you do.

When the debate is pared down to its essentials, it seems that the defenders of the apophatic tradition have one major argument on their side: God cannot belong in any category alongside us, because if He did, than that category would be larger than, and ontologically prior to, God. But is “person” (or more precisely, “personal being”) a category? By “personal being,” I simply mean a being to whom intelligence can be ascribed. I should point out that as I use the term, to call someone a personal being is not to say that they merely possess intelligence, as a property; a personal being may actually be Intelligence, as I would affirm that God is. Thus to call God a Personal Being, as I use the term, is not to limit Him or put Him in a genus alongside creatures. And Scripture itself tells us that God is a Spirit (John 4:24). The Baltimore Catechism says: “Although God is everywhere, we do not see Him because He is a spirit and cannot be seen with our eyes… God sees us and watches over us with loving care.” Does that strike you as anthropomorphic, Father, or would you agree, subject to qualifications?

What do I mean when I say God is intelligent? I mean that God is capable of directing His chosen means towards His long-term ends, and that He is capable (if He wishes) of telling us why He is doing so – in other words, He is capable of revealing His plans to us, using the medium of language. I believe, along with Duns Scotus, that the terms “know” and “love” may be predicated of God and ourselves univocally, because they are not modal verbs and they are not scalar verbs either: that is, they contain no references to how one knows and loves, or to what extent one is capable of doing so. They’re the only activities which don’t entail the existence of any limitations in the agent performing them.

While I agree that it is theologically accurate to describe God as Being Itself, I don’t think this description tells us anything positive about Him, except that He exists. To describe something simply as “a being” is completely uninformative, as it tells us nothing about the being’s causal powers, or its ways of interacting with other beings. To describe something as Being Itself merely tells us that there are no restrictions on its ways of interacting with other beings. But that tells us nothing positive about what it can actually do.

I also think that “Being Itself” cannot possibly be the ultimate way of describing God, because if it were, it would lead to some very odd ways of talking about God. For if God’s Nature is simply to be, then we should be able to substitute “Being” into statements about God and still make perfect sense. Now consider the following statements. “Being created the world.” “Being is love.” “Being loves you.” “Being knows everything.” “Being hates sin.” “Being is tri-personal.” None of these substitutions make sense. Why not? The answer, I would suggest, is that God is more than just “Being.” We need to describe God in a more positive way, but one which does not circumscribe Him.

It is for that reason that I prefer to characterize God in more personal terms, as Unlimited Intelligence and Love.

The main argument on the theistic personalist side is that it seems impossible to conceive of a God Who is not a self. Even you admit that Scripture is on the personalists’ side, Father. The God of the Bible constantly says “I” – even when He says “I am Who I am” – so He must be a Self of sorts. Also, if one adopts a Boethian account of Divine foreknowledge (as I do), then it follows that God’s knowledge must be (timelessly) determined by our free choices. God is the watcher in the high tower, to cite a medieval metaphor.

At the same time, I would have to say that God is one self, not three selves. I explain the Trinity to myself like this. God the Father is the Mind and Heart of God. God the Son is God’s knowledge of Himself, and God the Holy Spirit is God’s love of Himself. God loves Himself through knowing Himself, so the Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son.

I also believe God has experiences, because He chooses to let Himself have them. God invented the color red, the smell of ammonia and the taste of Danish cheese. How does He know any of these things if He can’t experience them in some fashion? Wouldn’t a God Who is incapable of having experiences be like philosopher Frank Jackson’s case of the blind scientist, Mary? One would pity such an impassible Being. God cannot be all “out” (active) and no “in” (passive). In order to fully know His creation, He must allow Himself to be determined by it. (Of course, that’s His choice.)

Finally, if God’s love is nothing like mine, if it’s not a feeling on His part towards me, then why should I love Him back? Why not just obey Him instead? After all, it’s not as if He’s going to appreciate any ardor on my part. If He’s a purely active being, then presumably all He wants back is actions on our part, not feelings. Or am I missing something?

LikeLike

Vincent, I’m delighted you have found EO. Welcome.

I ain’t no philosopher, but I’ll try to engage a couple of your points, at least as a way of pushing the conversation along.

I agree with you that the classical theistic concern is one of subsuming God in a category that is ontologically superior to him—and I would add, of putting God in a box alongside other “persons.” You ask if “person” should be understood as a category. Good question! I don’t know. It sure sounds like a category of some kind to me. Have you asked the folks over at Feser’s blog this question? I’d like to hear what they have to say. But it may be that once one has made all the qualifications you have made, then the classical theistic concern is satisfied. I have wondered about that myself.

I am a preacher, so of course I use personal terms by which to speak of God all the time. That’s what preachers do. That’s what pastors and spiritual counselors do. But over the past few years I have become a bit more aware of the limitations and dangers of this language. Consider these sentences:

Now this is just an ordinary way to express these things, but it sure sounds, without further qualification, as if you have described a temporal being. No doubt further qualifications are needed, but ain’t that the point?

Above I quoted a passage from Herbert McCabe. Let me requote it and ask what you think of it:

I do not have an opinion about modal vs scalar verbs. I first ran into the proposal that we may speak univocally of God in a book by William Alston many years ago and have not thought much about it since. I’m not sure if there really is much difference between what you are saying and Aquinas’s view. At some point along the line we just have to remember, and incorporate into our theories of theological language, the radical ontological difference between Creator and creature. Beyond that I am not committed to anyone’s particular theory.

(More later)

LikeLike

Hi Father,

Thanks very much for your gracious reply. Just to clarify, when I spoke of God as having long-term intentions, I meant intentions regarding events which we perceive as future, but not God. So I don’t envisage God as a temporal Being. In God’s Mind, past, present and future are logically (and ontologically) ordered, but not temporally ordered.

As for the passage you quoted from Fr. Herbert McCabe, I was a little shocked by this excerpt: “For us the business of being persons is extremely closely tied up with the business of talking, of forming concepts and making judgements but there is no reason at all to transfer all this to God; indeed there are strong reasons for not doing so…” Surely God talks to us (well, some of us, anyway). Surely He has concepts, even if He doesn’t form those concepts over the course of time. And surely He makes judgements: indeed, isn’t He going to do that on the Last Day? Or perhaps Fr. McCabe simply meant to say that God does not form judgements, since He already knows what is true. Later, he remarks: “If we do speak of God as making up his mind or changing his mind or deciding or cogitating or reasoning, it can only be by metaphor…” As far as the temporal aspect of these statements is concerned, obviously they’re metaphorical. But I think it’s accurate to say that when God judges that doing X is the best means of obtaining end Y, in His mind’s eye His concept of X is subordinated to His goal of Y, in some sort of hierarchical structure. I don’t think that’s anthropomorphic, but maybe I’m wrong.

LikeLike

Vincent, doesn’t it strike you as perhaps a tad odd thinking of the transcendent Creator as forming concepts or having beliefs or making judgments. I know that these are all things that we, as corporeal intellectual beings do; but how confident are we about importing this creaturely mode of rationality onto the infinite God? I’m not even sure if should think of angels in this way; but I this way of thinking about God as problematic. Surely this kind of language, when applied to God, is only analogical, at best.

How does the creator know the beings he has made? Does he not know them in the immediate and eternal act of creation? If this is the case, then his knowledge of created reality is utterly and radically different from the way we know anything.

But as I said, I ain’t no philosopher.

LikeLike

“While I agree that it is theologically accurate to describe God as Being Itself, I don’t think this description tells us anything positive about Him, except that He exists. To describe something simply as ‘a being’ is completely uninformative, as it tells us nothing about the being’s causal powers, or its ways of interacting with other beings. To describe something as Being Itself merely tells us that there are no restrictions on its ways of interacting with other beings. But that tells us nothing positive about what it can actually do.”

You raise what is, for me, an interesting question: What do we mean when we speak of God as Being itself? I haven’t thought much about this since seminary, when we read lots of Macquarrie, Tillich, and some Rahner. I don’t recall reading any Aquinas. Anyway, I’d love to hear everyone’s thoughts about the identification of God with Being. Is it only saying asserting that God exists? Do we not also identify God as Being in order to say something about him as creator, as the one who brings creatures into being and sustains their existence?

Since Dionysius many Eastern theologians have spoken of God as “beyond Being.” I’m unclear how literally we are to take this claim. Is it merely a rhetorical way of clearly differentiating uncreated and created, or is it saying something else? Met John Zizioulas has offered reservations about the “beyond Beyond” language:

I ain’t no philosopher. 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Cosmic Sky Dad | Orthodox Ruminations

Pingback: Hipsterdox | Cosmic Sky Dad