Acedia—everyone raise their hands who know how to pronounce this word correctly. If you don’t know or if you’re not absolutely sure, go back and click on the word.

Now that we all know how to pronounce acedia, what does it mean? The word derives from the Greek word akēdeia. The ancient ascetics used it to signify a specific spiritual condition that afflicts monks and indeed all people. Possible renderings into English include “boredom,” “inertia,” “sloth,” “apathy,” “repulsion,” “dislike,” “indolence,” “lassitude,” “dejection.” Hieroschemamonk Gabriel Bunge proposes Despondency as perhaps the most apt translation of the word, “if it is understood that in the term despondency the other shades of meaning are heard together” (p. 46).

Evagrius Ponticus puts acedia right in the middle of his list of the eight fundamental passions or thoughts (logismoi): gluttony, lust, avarice, sadness, anger, acedia, vainglory, and pride. He describes them as generic thoughts because, as Bunge writes, “not only are all other thoughts generated from them, but these eight themselves are interwoven in many various ways” (p. 40). One immediately notes that the list begins with the most sensual of the passions and concludes with the most immaterial. Underlying the eight is the unlisted root vice—philautia, love of self.

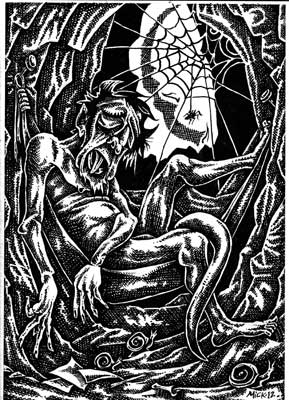

All who have seen Peter Cook and Dudley Moore in Bedazzled may be surprised to learn that before there were seven deadly sins there were eight. St Gregory the Great identified the capital sins as superbia (pride), invidia (envy), ira (anger), avaritia (avarice), tristia (sadness), gula (gluttony), and luxuria (disordered desire or lust). Over time tristia was replaced by otiositas or dēsidia (sloth, indolence). In Dante’s Divine Comedy, for example, sloth is described as tepid love, the failure to love God with all of one’s being (lento amore). In the popular imagination sloth has become equivalent to laziness, yet the Eastern Christian understanding of acedia enjoys a much richer meaning. Acedia, says Evagrius, is the “noon-day demon” that attacks the believer when the sun is at its highest and the heat unbearably oppressive. It is more than a flaw of character but an alien power that drains the person of energy and life, ultimately leading to spiritual death and sometimes even suicide, tearing “the soul to pieces as a hunting-dog does a fawn” (p. 121).

The eight logismoi of Evagrius combine in various ways, generating different psychic-spiritual outcomes; but acedia appears to be unique in one respect: “If it is true that, for the others, at any given time they are a link in a colorful and variously assembled chain, so it is said of despondency that it is always the terminus of such a chain, and is therefore not followed immediately by any other ‘thoughts'” (p. 53). It’s as if acedia makes it impossible for the other passions to operate, so enervating is the gloom. For this reason Evagrius identifies acedia as “the most oppressive of all demons” (p. 46). On the day that it strikes, “no other thought follows that of despondency, first because it persists, and then also, because it contains in itself nearly all the thoughts” (p. 57). Hence it is one of the most dangerous of the vices and the most difficult to combat, especially if it settles into a more or less permanent condition. The frustration of desire, inevitably accompanied by anger, fuels the deadly torpidity. “A despondent person hates precisely what is available,” Evagrius writes, “and desires what is not available” (p. 57). He is thus reduced to a state of irrationality, “dragged by desire and beaten by hatred” (p. 57). Bunge elaborates:

Acedia, therefore, has a characteristic Janus head, which clarifies its partially contradictory manifestations. … Frustration and aggressiveness combine in a new way and produce this “complex” (that is, interwoven) phenomenon of acedia. It is this very “complexity” that makes it so impenetrable for the affected one, who really feels that he is a “poor animal.”

Finally, a characteristic time factor may be added. The other thoughts come and go at times even very rapidly, for example those of impurity and blasphemy. In contrast, the thought of acedia, because of its complex nature, which unites in itself the most diverse other thoughts, has the characteristic of lasting for a long time. From that duration arises an entirely particular state of mind, such as is typical for depression. When it is not recognized in a timely manner, or rather when one refrains from applying the appropriate remedies, it can become more or less manifest as a permanent condition.

In the life of the soul, acedia thus represents a type of dead end. A distaste for all that is available combined with a diffuse longing for what is not available paralyzes the natural functions of the soul to such a degree that no single one of any of the other thoughts can gain the upper hand! (p. 58)

Not surprisingly, Evagrius observes, the resulting lethargy leads to the neglect of prayer and the despisal of all things spiritual:

A despondent monk,

is dilatory at prayer.

And at times, he does not

speak the words of the prayer at all.

Then, just as a sick person carries no heavy burden,

so the despondent monk never, at any time, performs

the work of God with care.

The sick person, indeed,

has lost the strength of life,

while in the monk, by contrast,

the resilience of his soul has gone slack. (p. 77)

Bunge summarizes the Evagrian understanding of despondency:

Acedia is a vice, a passion, from which man suffers in the truest sense of the word, as from all passions or diseases of the soul. And, like all passions, it has its secret, invisible roots in self-love (philautia), that all-hating passion, which manifests itself in a thousand ways as a state of being stuck in oneself that renders one incapable of love. Its secret driving forces are anger, aggressiveness, and that irrational desire which distorts all creation in a selfish way. (p. 133)

At this point, I suspect, most readers will probably recognize the passion of acedia as one that has plagued them at various points of their lives. We call it “depression,” and it enjoys multiple diagnostic codes in the DSM. How might we understand the relationship between the passion of acedia and the mental disorder of depression? Are they identical, mutually related, or totally different? Unfortunately, Bunge does not discuss this important question, perhaps feeling that it is beyond his scholarly competence, and leaves it to the reader to take up the challenge. One might be tempted to choose between the Evagrian and modern psychiatric understandings. This, I believe, would be unwise.

At this point, I suspect, most readers will probably recognize the passion of acedia as one that has plagued them at various points of their lives. We call it “depression,” and it enjoys multiple diagnostic codes in the DSM. How might we understand the relationship between the passion of acedia and the mental disorder of depression? Are they identical, mutually related, or totally different? Unfortunately, Bunge does not discuss this important question, perhaps feeling that it is beyond his scholarly competence, and leaves it to the reader to take up the challenge. One might be tempted to choose between the Evagrian and modern psychiatric understandings. This, I believe, would be unwise.

Bunge devotes a chapter to the ascetical remedies to acedia. He presents no magical cures. Unlike the modern physician who is likely to give his patient a prescription for Zoloft or Cymbalta and leave it at that, Evagrius understood that the condition, particularly in its severe forms, requires sustained attention and disciplined application of the appropriate remedies. The demon does not flee easily. Yet despite the demonic stubbornness and the complexity of the passion, Evagrius believes that through patient perseverance the believer can achieve genuine victory:

Patience: a crushing of despondency. (p. 90)

The spirit of despondency

drives the monk from his cell,

but the one who has endurance will always have rest. (p. 117)A deified intellect is an intellect that from all agitation has arrived at peace and has been adorned with the light of the vision of the Holy Trinity and begs of the Father the fulfillment of a desire that is insatiable. (p. 131)

Evil is a parasite and has already been defeated on the cross of the Son of God. Alien and unnatural to the world, it has no future. “There was a time when evil did not exist,” asserts Evagrius, “and the time will come when it will exist no more” (p. 44). Humanity was not meant for despondency. Those of us who have struggled with chronic depression will be understandably skeptical. We know too well the limits, and disappointments, of counseling and pharmacology in the treatment of our depression; yet Evagrius understood something that we moderns have forgotten: we are beings who live simultaneously in two realms—the physical and the spiritual—and the spiritual realm is populated by demonic agencies that are seeking to destroy us through passions and mental disorders. “For we do not wrestle against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the cosmic powers over this present darkness, against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly places” (Eph 6:12). We are involved in spiritual warfare, whether we believe in demons or not. Our skepticism does not change the reality. The ascetical tradition provides us with weapons and therapies that may and should be employed both against the evil supernatural powers and our disordered desires.

I will not discuss the Evagrian remedies in this review. It is best that you purchase or borrow Despondency: The Spiritual Teaching of Evagrius Ponticus and slowly and carefully read the book yourself. You may well discover, as I did, that you need to read it a second time (and probably a third and fourth time); and then discuss it with a wise spiritual guide and soul friend. One word of advice: do not throw away your meds or terminate your secular counseling. A few years ago I saw such counsel being dispensed on an Orthodox internet forum and was horrified. The relation between brain chemistry, moods, and spiritual states is a mystery. We must not toss aside whatever knowledge we have gained from science and depth psychology.

In the beginning of his book Father Gabriel quotes a story of St Antony the Great. This story will serve as a fitting conclusion to this review:

When the holy Abba Antony lived in the desert he was beset by acedia and attacked by many sinful thoughts. He said to God, “Lord, I want to be saved but these thoughts do not leave me alone; what shall I do in my affliction? How can I be saved?” A short while afterwards, when he got up to go out, Antony saw a man like himself sitting at his work, getting up from his work to pray, then sitting down again and plaiting a rope, then getting up to pray again. It was an angel of the Lord sent to correct him and reassure him. He heard the angel say to him, “Do this and you will be saved.” At these words, Antony was filled with joy and courage. He did this, and he was saved.

Take heart, my friends. Christ has conquered the world (Jn 16:33).

I think Dante does a good job of preserving the subtleties of Acedia within the Divine Comedy, even though he’s only got 7 vices to work with.

LikeLike

Steve, would you mind elaborating. It’s been several years since I last read the Inferno and Purgatorio. What in particular impresses you about Dante’s treatment of sloth. Not trying to put you on the spot. I just thought it might be helpful and interesting.

LikeLike

Dante’s consideration of sloth begins in the very beginning of the Inferno:

“I cannot well repeat how there I entered,

So full was I of slumber at the moment

In which I had abandoned the true way.”

I have a very particular reading of the Divine Comedy where I read Sloth as a meta-vice, a sort of precursor to all other vices, which contains all other vices. The terrace of Sloth in the Purgatorio stands in the very middle of the Divine Comedy, numerically (i.e. the 50th Canto). Time, and wasting time, are central to the entire Commedia, but especially the Purgatorio.

During the Inferno, Virgil exhorts Dante to not be lazy, not be afraid, and to be brave and keep pushing on when things get tough. I think it highlights an aspect of Acedia that I don’t think you mentioned: fear or cowardice. I think some of the church fathers you mentioned discuss cowardice related to Acedia, but I don’t remember, I don’t have any quotes at hand for that.

LikeLike

Thank you, Steve. Bunge mentions that Evagrius also connects acedia to cowardice, but he doesn’t provide a quotation that explains or amplifies the connection.

LikeLike

I think the connection resides in the general idea of inaction. The slothful are stuck. It’s like being out on a battlefield and being unable to move, whether through fear or sadness.

LikeLike

… I couldn’t have received a better Birthday gift … Fr. G-d Bless and thank you… john

LikeLike

Acedia is a new term for my ever growing comprehension of depression and despair. I live with despondency daily.

LikeLike

Just added the book to my wish list. I think it’s worth reading as it is a struggle I sometimes seem to have.

LikeLike

And just to add, I appreciate the disclaimer that both spirituality and psychiatric treatments need not be in contradiction, and that is a very prudent and wise part of your post.

LikeLike

Click to access NaughTeachNoteCh3Lei.pdf

The above link has some good thoughts, largely derived from Josef Pieper’s very fine book on Hope. Acedia is a complicated condition. I don’t think acedia is technically the same as depression.

There are also different notions of the self. Some allow Evagrius’ interpretation to stand. Others would not. What I find dangerous and not quite right is the moralizing take on depression — as if it were largely a function of egotism and individual sin. In my view, depression does probably have some chemical factors and it can be a sinful indulgence. Beyond that, it is often a response to a fallen world that is legitimately depressing.

One needs to distinguish between metaphysical despair and psychological depression, in any event. S.L. Frank and Luigi Guissani both see the sadness of the human being in the face of the world a sign of human greatness. The spirit is not satisfied with finitude. It cannot be made happy with anything less than God.

LikeLike

I agree with you, Brian, but the very fact that “the spirit …cannot be made happy with anything less than God” contributes immensely to the very state of acedia or disconsolate despair. If one has lost their belief in God, then they are beyond mere dissatisfaction; they are staring into the abyss. Although the connection will always remain, the person who feels bereft is still sailing without a rudder. Psychological and the spiritual health seem innately bound.

LikeLike

Yes, I think you are right.

Yet, though I have a strong belief in God and hope for the ultimate transfiguration of the cosmos, I still have to wrestle with depression. Perhaps the saints get past the “tears of things”, though what I have read of Mother Teresa, for example, suggests it is not always so.

LikeLike

“What I find dangerous and not quite right is the moralizing take on depression — as if it were largely a function of egotism and individual sin.”

I had a different response to the book, and it may be that I simply have not presented Evagrius’s thoughts on acedia accurately. By locating his analysis of logismoi in the domain of spiritual warfare, Evagrius has made impossible the reduction of acedia to a matter of moralism. Consider, e.g., this statement by Fr Bunge: “For Evagrius, passions, sins, are always something ‘alien’ that is forced upon us from outside, something that expresses itself in the ‘darkness’ and ‘confusion’ of the intellect” (p. 128).

Of course, he would be reluctant, I suspect, to eliminate all personal responsibility, which would mean that I, the depressed person, am totally helpless and therefore not only cannot be held morally responsible for my actions but am incapable of contributing in any way to my healing and liberation. I have struggled with serious depression all of my adolescent and adult life. I know the darkness intimately. I know the suffering and despair. To my surprise, I found this to be a hopeful book. It may be that I will never be able to effectively apply the recommended ascetical remedies, yet I am finding that Evagrius’s way of looking at depression to be potentially liberating. I don’t know if this makes any sense. I don’t know if it makes any sense to me either.

I am told that there are similarities between the Evagrian “therapy” and cognitive therapy. I don’t know, though, if anyone has actually written anything about this, though.

Another passage from Bunge:

Do take a look at Fr Gabriel’s book and let me know what you think.

LikeLike

Father,

You know, when I get especially upset with life, I buy art prints that I never frame (I stick them in a closet. I need a new house to actually hang them) and I buy theology books. (Things have been going swimmingly; I have five books on order — one on Julian of Norwich that I think you might like. I’ll let you know.) I will put Fr. Gabriel’s book next in the queue.

I should clarify that I was not actually interacting carefully with the blog post. I think you wrote well. I was mainly reacting to something I have sensed in a couple of Orthodox books on the matter, plus also my own past conversations with various religious folk.

Evagrius, btw, is one of those figures that seems to divide. Eckhart is a western spiritual who always seems to invite very different interpretations. I usually go with the interpretation that is most generously orthodox and amenable to my own understanding. This is probably not the best scholarship, but it’s how I choose to proceed. In any event, I am sure there is a lot in Evagrius to learn from and the passages you quote seem excellent to me.

LikeLike

A great book on the topic is “Where the Roots Reach for Water” it is a personal and historical approach to what the author calls melancholia. It is a complex narrative but some things I gleaned from it: it is not always a disease and always treating it that way is counter productive; even when it is a disease it has environmental, epigenetic and spiritual roots.

The most fascinating part of the book to me was as the author was working with a counselor when all pharmacological approaches had failed, except from some help from a naturopathic remedy, the counselor asked, “What does your depression want to teach you?”

At the end of the book, he had returned to his spiritual roots and married but was still working on balance. He discovered that he had to go through the darkness to get to the other side rather than always fighting it.

IMO, being active, happy and “productive” all the time is a modern invention that does great damage to humanity in general but especially to the empathic people who need time to process all of the inputs to which they are subject. As you rightly point out brian, there is much that causes grief and sadness. There are some people who feel the sadness and pain of others as much as their own. Sometimes, withdrawal is necessary. If not managed properly, that withdrawal can easily turn to depression and/or anger, substance abuse and even the temptation to nothingness that the noon day demon promises. There is little place in our culture for such people–perhaps the best among us in some ways.

It seems likely that Robin Williams, for instance, was one such. His humor was a defense that, to me, was deeply tinged with the sadness of the human condition. He did not have God, so he had to be always ‘on’. In interviews I have read he talked about the temptations he suffered when it came to alcohol and cocaine–seemed like the voice of the noonday demon to me.

May our Lord lead us to wisdom and the strength to bear the suffering of love.

LikeLike

I am SURPRISED that no one has yet commented on my reference to the classic movie Bedazzled, perhaps the greatest commentary on the seven deadly sins within the Western tradition. (I’m not talking about the terrible remake.) 😀

LikeLike

I’ve never seen it before, sorry.

LikeLike

Then by all means rent the DVD. It’s a wonderful comedy. Peter Cook and Dudley Moore were quite the British comedy team.

LikeLike

Bedazzled is a wonderful movie. 2 things: the devil always lies and he gets us frequently in the little annoyances not the big ones difficulties. A testament that watchfulness is essential.

O, that and a young Raquel Welch as Lust. O well……

It is not a commonly known movie.

LikeLike