On 27 November 2014 I gave a talk titled “St Isaac the Syrian, Apokatastasis, and the Renewal of Orthodox Preaching” at the first Theotokos Institute Conference in Cardiff, Wales. An expanded, footnoted version of the talk will be published in the journal Logos: A Journal of Eastern Christian Studies in 2016. I am grateful to the Theotokos Institute for the invitation to deliver this address and for the helpful and encouraging responses from the conference participants. I have divided my talk into three sections: (1) St Isaac the Syrian and Apokatastasis, (2) the Proclamatory Rule of the Gospel, and (3) Preaching the Kingdom. Please do not reblog or reproduce these articles without permission.

* * *

I know that many of you are now silently protesting, “We have never heard of such a hermeneutical rule.” George Lindbeck has a ready rejoinder: “Rules can be followed in practice without any explicit or theoretical knowledge of them” (The Church in a Postliberal Age, p. 43). Homer was a supreme master of Ionic Greek long before the grammatical rules of the language were codified. One may speak a language well without being able to state the rules that govern the language. Hence it is at least possible—and I would argue highly probable—that from Pentecost on Christians have lived, known, celebrated, preached, and sacramentally enacted the unconditionality of grace, even in the absence of an explicit regulative canon. It is also highly probable, indeed certain, that at various times and places pastors and preachers have compromised the gospel by reducing the free gift of salvation to a work that must be earned.

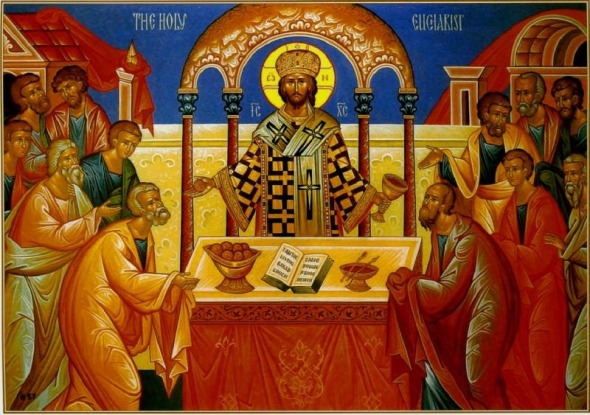

I invite you to consider the proclamatory rule in light of the eschatological nature of the Holy Eucharist. In recent decades Fr Alexander Schmemann and Met John Zizioulas have powerfully argued for a recovery of the eschatological dimension of the Eucharist. Schmemann speaks of the Eucharist as the “sacrament of the Kingdom”; Zizioulas, “the icon of the Kingdom.” Zizioulas loves to quote the words of St Maximus the Confessor: “For the things of the Old Testament are the shadow; those of the New Testament are the image. The truth is the state of things to come” (The Eucharistic Communion and the World, p. 44). The Church lives from the future. The kingdom that is to come causes the Eucharist and confers upon it its true being. The Divine Liturgy does not merely commemorate the events of past history: it blesses, invokes, and anticipates the future; it even remembers the future. “Blessed is the Kingdom of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit,” the celebrant intones at the beginning of the liturgy. At the Great Entrance he declares to the assembly: “May the Lord God remember all of you in His kingdom, now and forever and to the ages of ages.” And the anaphora of St John Chrysostom strikingly recollects not only the cross and resurrection of Christ but also his “second and glorious Coming.”

In the Mystical Supper the risen and ascended Son comes to the Church from his eternal futurity; or, to make the same point in different imagery, in the Supper the Church is lifted up by the Spirit into the heavens and united to the Messianic Banquet. The kingdom is Jesus Christ, risen, glorified, returning. Zizioulas elaborates:

What we experience in the divine Eucharist is the end time making itself present to us now. The Eucharist is not a repetition or continuation of the past, or just one event amongst others, but it is the penetration of the future into time. The Eucharist is entirely live, and utterly new; there is no element of the past about it. The Eucharist is the incarnation live, the crucifixion live, the resurrection live, the ascension live, the Lord’s coming again and the day of judgment, live. (Lectures in Christian Dogmatics, p. 155)

As the Metropolitan of Pergamon elsewhere states, “In the Eucharist, we move within the space of the age to come, of the Kingdom” (Eucharistic Communion, p. 57).

To proclaim the gospel in the mode of unconditional promise is to speak the language of the parousia. The words of the preacher become words of prophecy bearing the living reality of the eschaton. The gospel is nothing less than the final judgment proleptically let loose into history. It thus confronts us with decisive authority, an authority not of law and condemnation but of blessing, forgiveness, and hope—the authority of apokatastasis.

When the preacher obeys the hermeneutical rule, he moves from talking about salvation to giving salvation. This move from second-order discourse to present-tense proclamation is crucial. As long as the preacher remains within the mode of description and explanation, the kerygmatic Word remains unsaid. Every homily is of course informed by the preacher’s own exegetical reflections about the appointed biblical text, as well as by his reflections on how the text has been interpreted within doctrinal and pastoral tradition. But at some point he needs to move from saying words about God to actually speaking gospel in the name of God. (See the letter Gerhard Forde wrote to me thirty years ago; also see his book Theology is for Proclamation.)

As an analogy, consider the difference between the language of lovers and the language of psychologists. Psychologists can tell us all about what lovers experience, what they feel and do, how love changes and energizes them. It’s all quite informative. But when you are in love, this kind of information is not what you want to hear from your lover. What you want to hear, what you need to hear, is “I love you.” This simple declaration makes all the difference.

Gospel-preaching occurs when the message becomes salvific deed and act. The Word of God effects what it announces and does what it proclaims. By the unconditional promise of Christ Jesus, the preacher converts, justifies, regenerates, illumines, deifies his hearers. He communicates salvation. He doesn’t just speak about salvation—he does it; he performs it. By the gospel of resurrection the preacher re-creates the world of his hearers in the power of the Spirit. Sinners are absolved, saints are made, new life is bestowed. The homily thus becomes eschatological event that slays the old being and births the new. “The proclamation of the Word,” Schmemann writes, “is a sacramental act par excellence because it is a transforming act. It transforms the human words of the Gospel into the Word of God and the manifestation of the Kingdom. And it transforms the man who hears the Word into a receptacle of the Word and a temple of the Spirit” (For the Life of the World, p. 33).

When the preacher instead presents the good news of Christ in the form of conditional promise and synergistic transaction, he violates the eschatological reality of the Eucharist. It doesn’t matter if he does so for moralistic, ascetical, or doctrinal reasons. The result is the same—the good news is reduced to law. The gospel tolerates no conditions, for in the kingdom there is no longer time for the fulfillment of conditions. The kingdom has come. In response there can only be faith or offense. We either find ourselves celebrating the joyous gift of eternal life or cursing the uncreated radiance.

Brothers and sisters, Jesus is risen! He comes to us in his Word in utter grace, infinite charity, unmerited forgiveness, startling generosity, omnipotent benevolence, transforming holiness, deifying triumph—this is the gospel we are commissioned to declare. Amen.

© 2014 Alvin F. Kimel

Dear Fr in Christ Aidan,

Allow me to ask for your permission to reblog your remarkable talk to my Fratres and Sorores of the Autonomous Catholic Church of Antioch.

In the light of Christ and the Theotokos, Fr roger in Xp (hon.Canon,hon Ambassador of Belgium) Fr Aidan Kimel posted: “On 27 November 2014 I gave a talk titled “St Isaac the Syrian, Apokatastasis, and the Renewal of Orthodox Preaching” at the first Theotokos Institute Conference in Cardiff, Wales. An expanded, footnoted version of the talk will be published in the journal”

LikeLike

Roger, feel free to reblog the first paragraph of my talk, but please direct your readers to my blog here if they wish to read the articles in their entirety. Thanks.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan, I want with all my heart to believe the Gospel unconditionally as you present it. That’s the way I love my own kids. St. Paul however always seems to offer a caveat after presenting the Gospel. For instance he has an awesome presentation in Galatians on how we are save like Abraham without the law– adopted as sons. And then in chapter 5, he has to add a list of sins and the warning that “they will not inherit the kingdom of God”. So is he saying that God loves us unconditionally, outside of the moral law, but if you end up in one of these sins you won’t be in the kingdom. It seems to be a denial of all he just said. Now it becomes dependent on me not indulging on any of the listed sins and not predicated on unconditional acceptance “outside the works of the law”

Of course I may not want to indulge in those sins but it often takes years for a Christian to even begin to extricate those sins from his life. Think of a born homosexual who lives that way for many years and is “married” with several kids. They may receive Christ but it may take years to begin to live as a celibate. That’s just one example. How do you reconcile this? I always feel like God will love unconditionally but He is ready to “give me over to my sins” if I start to slip and ultimately let me go to Gehenna.

LikeLike

Stephen, you have posed one of the most difficult challenges to the unconditionality of divine grace. And you are right–one can easily find texts, even in the Apostle Paul, that seem to argue against it. At the very least these texts (and we all know which ones they are) are plausibly construed as supporting the position that God is both helpless when confronted by free creaturely rejection and that he has set a “time limit” on repentance–hence the logical inference that eternal damnation is a possibility and the probability assessment that some, many, or most will irrevocably reject God’s offer of forgiveness.

Descriptively, I think it is absolutely true that only the pure in heart will, and can, see God. Our wills must be perfectly conformed to the divine will. We must become holy as Christ is holy. And so on.

Yet is that all we want to say on the matter? Are we trapped in this logic? Is God trapped in this logic?! St Isaac did not think so.

The Father does not love his children less than we love our own children, nor is the divine freedom constrained by the limits of creaturely freedom.

LikeLike

Al – thought provoking and encouraging! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Is it possible that “not inheriting the Kingdom of God” is not the same as not entering the Kingdom of God? I get that if I am an adulterer or the town gossip, I may not inherit love, joy, peace patience kindness, gentleness etc.– at least not in its fullness. So in that since that admonition makes perfect sense. But if that means that if I as a Christian fall into some sin for some length of time given our fallen nature, I don’t enter the Kingdom of Heaven, then I am in big trouble. How many times do you have to gossip to be considered a gossip or be wrathful to be considered “unworthy of the kingdom”. It’s that kind of pulse keeping that tends to put my conscience straight back under the Law. Arrggg.

LikeLike

Inheriting life is equated with entering the kingdom in Mk 10. So, I do not think we can say inheriting the kingdom and entering the kingdom are two separate things…

LikeLike

Stephen:

Well, everyone is unworthy of the kingdom. That’s simple. A danger here is that one may become like a spiritual hypochondriac, caught in a scrupulosity that is trying to discern just how advanced the case may be.

Honestly, I think Father’s comment is on point. The kind of ordinary logic we often bring to these discussions is inadequate. Paradox is necessary for Christian theology. The Triune God just doesn’t fit with the perspective of “euclidean geometry,” nor does divine justice.

One of my favorite quotes from Henri de Lubac: “but do not presume that you know what love is.”

What I know for sure is that divine love cannot be less than human compassion and human hope, especially since all our loves and, in my opinion, even our ordinary capacity to perceive is “always already” a form of grace.

LikeLike

“But when you are in love, this kind of information is not what you want to hear from your lover. What you want to hear, what you need to hear, is “I love you.” This simple declaration makes all the difference.”

I’m with you Father. The last time I saw my friend before she left off for school, she was letting me rest my head on her shoulder. It was a gentle moment but I also demanded the pat on the head and for her to say, “Yes I do” every time I said, “My friend loves me”.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan,

Do you think that my interpretation that “inheriting” the kingdom of god as d entering it are not the same thing? St. Paul’s warning then makes sense in the context of Galatians. As he says elsewhere a man will be saved as through the fire yet will suffer lose.

By the way I don’t disagree with your conclusions, I’m just trying to make some sense of the perceived contradictions in scripture.

Please keep posting more of your thoughts on this subject or even some of the reactions of your talk in Wales.

LikeLike

Your entire series on the Apokatastasis just blessed my socks off.

LikeLike

I agree! The series on St. Isaac the Syrian and the one of Sergius Bulgakov forever changed my life:)

LikeLike

Reblogged this on padrerichard.

LikeLike