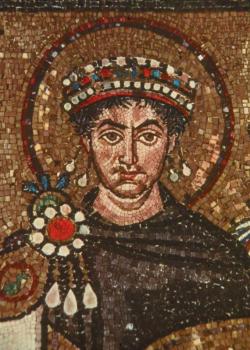

The folks at Classical Christianity posted today a passage from St Justinian’s letter to Patriarch Menas criticizing universal salvation. This is the letter in which the Emperor commanded the patriarch to convene a synod to condemn the teachings of Origen. To it he appended the nine anathemas that were eventually confirmed by the 543 Synod of Constantinople. Here’s the passage:

Will render men slothful, and discourage them from keeping the commandments of God. It will encourage them to depart from the narrow way, leading them by deception into ways that are wide and easy. Moreover, such a doctrine completely contradicts the words of our Great God and Savior. For in the Holy Gospel he himself teaches that the impious will be sent away into eternal punishment, but the righteous will receive life eternal. Thus to those at his right, he says: “Come, O blessed of my Father, and inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world” [Mt 25:34]. But to those on his left, he says: “Depart from me, you cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels” [Mt 25:41]. The Lord clearly teaches that both heaven and hell are eternal, but the followers of Origen prefer the myths of their master over and against the judgments of Christ, which plainly refute them. If the torments of the damned will come to an end, so too will the life promised to the righteous, for both are said to be “eternal.” And if both the torments of hell and the pleasures of paradise should cease, what was the point of the Incarnation of our Lord Jesus Christ? What was the purpose of his crucifixion, his death, burial, and resurrection? And what of all those who fought the good fight and suffered martyrdom for the sake of Christ? What benefit will their sufferings have been to them, if in the “final restoration” they will receive the same reward as sinners and demons? (Against Origen PG 86.975 BD)

Justinian advances four objections to the universalist hope:

First, universalism encourages moral indolence and wickedness. Why be obedient if we are all going to be saved in the end anyway? Origen was, in fact, sensitive to this criticism. He knew that the unconverted and spiritually immature might well exploit the universalist hope to justify continued sin and disobedience. Consequently he suggested that apokatastasis should only be shared with the spiritually mature, i.e., with those who already “grasp the mysteries of Scripture” and thus desire to do good out of love, not fear (Hom. in Luc. 22.5). Writing after Justinian and the conciliar condemnation of apokatastasis, St Maximus the Confessor alludes to the universalist hope as a teaching that we should “honor with silence.” St Gregory of Nyssa, on the other hand, clearly speaks of the apokatastasis in his Great Catechism and other writings, apparently believing that it belongs to the apostolic vision of the Eschaton and thus properly shared with all the baptized.

Justinian’s criticism implies that fear of damnation is a stronger motivational force for repentance than love and the hope of eternal happiness. Is this true? Perhaps so at the societal level. As emperor, Justinian had to be concerned with the order and unity of the empire. Given the symbiotic union of Church and State that existed in the sixth century, I can understand why Justinian and others might fear the proclamation of universal salvation. But at the level of gospel, we must ask, What kind of faith does the threat of eternal damnation generate? Does faith based on fear save?

Sergius Bulgakov emphatically rejected the employment of infernal terror to induce faith and repentance. Not only can it not attain its salvific goal, but “striking sensitive hearts with horror, paralyzing filial love and the childlike trust in the Heavenly Father, this idea makes Christianity resemble Islam, replacing love with fear. Salvific fear, too, must also have its measure, and not become an attempt to terrorize” (The Bride of the Lamb, p. 484).

Second, universalism contradicts the testimony of Christ Jesus himself. Our Lord expressly teaches in his parable of the final judgment that the wicked “will depart into eternal [aionion] punishment, but the righteous into eternal [aionion] life” (Matt 25:46). If perdition should prove to be only temporary, Justinian argues, then that would logically imply that the life of the Kingdom will also be temporary. Clearly the Emperor, perhaps along with the majority of his fellow sixth century Greek speakers, reads aionion as signifying eternal, unending, interminable, everlasting. But this is not what the word principally meant in first-century, as recognized by Origen himself: “In Scriptures, αἰών is sometimes found in the sense of something that knows no end; at times it designates something that has no end in the present world, but will have in the future one; sometimes it means a certain stretch of time; or again the duration of the life of a single person is called αἰών” (Comm. in Rom. 6,5). Origen’s judgment has been confirmed by recent scholarly research. Thus Ilaria Ramelli:

As for the NT, the points that could be interpreted as teaching an eternal damnation, and therefore contradicting the theory of apokatastasis, consist in the few passages that mention a πῦρ αἰώνιον, a κόλασις αἰώνιος, a fire “that cannot be quenched” and a worm that “does not die” (see, for instance, Matt 18:8–9; 25:41). Now, such expressions, rather than signifying an infinite duration, indicate that the fire, punishment, and worm at stake are not those of human everyday experience in this world, in which fire can be extinguished and worms die, but others, of the other world or αἰών. The adjective αἰώνιος in the Bible never means “eternal” unless it refers to God, who lends it the very notion of absolute eternity. In reference to life and death, it means “belonging to the future world.” It is remarkable that in the Bible only life in the other world is called ἀΐδιος, that is, “absolutely eternal”; this adjective in the Bible never refers to punishment, death, or fire in the other world. These are only called αἰώνια. (The Christian Doctrine of Apokatastasis, p. 26.

The words of Christ regarding eonian punishment read very differently if interpreted as meaning “the punishment of the future age.” But apparently at some point in the Greek-speaking world, the original meaning of aionion was lost and the word exclusively, or at least principally, came to mean eternal. It should also be noted that when St Jerome translated the New Testament into Latin, he used the word æternum to render aionion: “Et ibunt hi in supplicium æternum: iusti autem in vitam æternam” (Matt 25:46). Western Christians never had a chance.

Third, universalism undermines the saving work of Christ’s. If all will ultimately be saved, what was the point? I find this the weakest objection of all. Is the soteriological significance of Jesus’ death and resurrection diminished or rendered irrelevant if they ground the salvation of every human being instead of just some? Has not the Apostle Paul assured us that God our Savior desires the salvation of all (1 Tim 2:3-4)? Or are we forced in the end to admit that heaven needs hell? I suspect that Justinian believes that the Origenian doctrine of apokatastasis involves a kind of metaphysical necessity or coercion, thus negating human freedom. Perhaps this was what the 6th century Origenists were in fact teaching. If God can save all by an exercise of omnipotent will, then the Incarnation becomes mere charade. But that is certainly not what Origen or the Nyssen taught, and it’s certainly not what contemporary universalists such as Tom Talbott teach.

Fourth, universalism implicates God in injustice. Would it not be inequitable, asks the saint-emperor, if the impious were to receive the same reward as those who shed their blood in martyrdom? I wonder if Justinian had ever read the parable of the workers in the vineyard (Matt 20:1-16):

“For the kingdom of heaven is like a householder who went out early in the morning to hire laborers for his vineyard. After agreeing with the laborers for a denarius a day, he sent them into his vineyard. And going out about the third hour he saw others standing idle in the market place; and to them he said, ‘You go into the vineyard too, and whatever is right I will give you.’ So they went. Going out again about the sixth hour and the ninth hour, he did the same. And about the eleventh hour he went out and found others standing; and he said to them, ‘Why do you stand here idle all day?’ They said to him, ‘Because no one has hired us.’ He said to them, ‘You go into the vineyard too.’ And when evening came, the owner of the vineyard said to his steward, ‘Call the laborers and pay them their wages, beginning with the last, up to the first.’ And when those hired about the eleventh hour came, each of them received a denarius. Now when the first came, they thought they would receive more; but each of them also received a denarius. And on receiving it they grumbled at the householder, saying, ‘These last worked only one hour, and you have made them equal to us who have borne the burden of the day and the scorching heat.’ But he replied to one of them, ‘Friend, I am doing you no wrong; did you not agree with me for a denarius? Take what belongs to you, and go; I choose to give to this last as I give to you. Am I not allowed to do what I choose with what belongs to me? Or do you begrudge my generosity?’ So the last will be first, and the first last.”

Clearly the kind of justice that interests the Emperor Justinian does not interest the eternal Judge of the universe. That it does not is our salvation.

Fr. Aidan,

Are you a universalist?

Maximus

LikeLike

Maximus, I’m happy to locate myself with the universalist hope shared by Origen, St Gregory of Nyssa, St Gregory of Nazianzus, St Isaac the Syrian, Sergius Bulgakov, Paul Evdokimov, Met Kallistos Ware, and Met Hilarion Alfeyev.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan,

Origen and Origenism was condemned by the Councils and and a host of Saints. Fr. Bulgakov’s doctrines were very controversial in his day (Sophianism, Origenism, commemorating the Pope of Rome as a priest of the Russian Church, and advocating for intercommunion with Anglicans) and condemned by the ROC and ROCOR. Why would one leave the Councils and the majority for idiosyncratic doctrines held by a minority? Especially since some of that minority is either condemned or controversial. St. Paisios the Athonite, echoing Sts. Barsanuphius and John, said that we should not follow the example of the Saints’ imperfections because we may end up justifying weakness or falsehood.

St. Gregory the Theologian was a universalist?

Perhaps a hope can be held privately but it seems as though you offer an apologetic. I doubt that some on this blog even care “what the Councils and Saints say” by the way some spoke about St. Justinian in your prior potsts. But if we can’t follow the Councils and the Fathers as Orthodox, what is the alternative and where will we end up?

LikeLike

And don’t forget Clement of Alexandria and St. Macrina the Blessed.

LikeLike

The Greek Fathers misinterpreted Greek, and St. Jerome misinformed the entire Latin Church and all the Holy Fathers of the West?

LikeLike

Is it so implausible that after 500 years people might not correctly understand the meaning of certain NT words and expressions? The meanings of words change all the time. Just consider our difficulties in correctly interpreting the plays of Shakespeare.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fr. Kimel,

I believe that the Holy Spirit guides the Church and enlightens her Saints, or in other words, in Holy Tradition. So it’s not quite like a bunch of scholars arguing about how to interpret Shakespeare. That’s Protestantism actually: a bunch of scholars arguing over the Biblical text. They do so mainly because they have a text without the Tradition and authority of the Church.

LikeLike

Origen was clear about the distinction between aionios and aidios at the beginning of the 3rd century, no?

LikeLike

Yes.

LikeLike

Dallas, Ramelli and Konstan devote several pages to Origen in their book Terms for Eternity.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan,

I can’t locate it but I know of a quote where Met. Hilarion actually stated that he wrote the book about St. Isaac’s doctrines, not his own. In his Orthodox Christianity series published by SVS press he states: “the Orthodox Church is far from the excessive optimism of those who maintain that at the end time God’s mercy will extend to all of unrighteous humanity and all people, including great sinners, and together with them the devil and his demons will be saved in a lofty form by will of the God who is good.” (Vol II, pp 557-558) On pg 561 he states that the Origenist supposition on the salvation of the devil and his angels is in “radical opposition to church tradition” and “contradictory to the Gospel”. He goes on to address St. Gregory, what other Saints thought about his error, St. Maximus (who + Hilarion proves does not hold to universalism), and Fr. Bulgakov. He also states that: “opinions of individual theologians and philosophers defending the teaching of universal salvation do not grant it legitimacy as a teaching of the Church.” It’s all in the chapter 31 “Posthumous Retribution”.

LikeLike

That’s quite interesting about Met Hilarion. If what you write is correct, then it appears that he has changed his mind since he wrote his book The Mystery of Faith.

LikeLike

Fr Aidan, Maximus’s quotes are a far cry from this statement by Met. Hilarion in 2008:

“God does nothing out of retribution. Even to think that way about God would be blasphemous. Even worse is the opinion that God allows people to lead a sinful life on earth in order to punish them eternally after death. This is a blasphemous and perverted understanding of God, a calumny of God… quite to the contrary, the majority of people will find themselves in the Kingdom of heaven, and only a few sinners will go to hell, and even they only for the period of time which is necessary for their repentance and remission of sins.” (speech to ‘The World Congress on Divine Mercy’, Rome April 2008).

This brings me to a serious, very practical question. I don’t know how others here feel, but I have to say that for me the very thought that God could do anything apart from His love, and out of sheer retribution, is an exceedingly repugnant thought, and indeed blasphemous. On a personal level I can accept those who do hold to the retributionist position simply by not judging them and remembering that I at one time accepted that traditional viewpoint too. But the pressing question for me is this: How are we to look at the saints who held such views? How do we account for the fact that it is on such saints that the Church was built? How do we deal with the fact that so few Orthodox saints were vocal about their belief that God’s love will not fail? I’m afraid it comes down to this: How do I not doubt the Orthodox Church herself when so many saints had a view that in reality has no room for pity for those who die slaves to sin, who know not what they do? It won’t do to answer simply that we are ALL (including the saints) fallen. (That is a given!) It’s just that it is hard to trust a Church that does not actively affirm the “good” in the Good News.

One note: I know that there are many good people who would argue that the belief in eternal conscious torment does not mean God is not good or that God’s love ultimately fails. That discussion could go on interminably. I’m speaking only for me and at least a few others who believe at the core of their being that the Gospel isn’t the Gospel if God does not fulfill His promise to heal all creation and draw all men to Himself.

LikeLike

Connie, I have ordered Hilarion’ new book to see exactly what he is now saying.

LikeLike

Connie, great comment full of great thoughts and questions.

LikeLike

Thank you Mike. These questions have been plaguing me for many years.

LikeLike

IMHO, it is precisely this concern that necessitates an Orthodox theory of doctrinal development.

LikeLike

Well, while we wait for that to happen 🙂 I would love to see you write a response to those out there who may believe in apocatastasis but think it is folly to openly promote it. To me it seems like a strange stance since an open espousal of Christian universalism has returned many to Christ, though not necessarily to Orthodoxy.

LikeLike

Connie, I had an opportunity to glance at the chapter on eschatology of Met Hilarion’s (big) book on Orthodox Christianity. I’m afraid that Maximus is correct. Hilarion has apparently changed his mind about the universalist hope. He still acknowledges that an individual’s destiny is not definitively settled until the future coming judgment, and he still sounds the rhetoric of God’s love and philanthropia; but he insists that apokatastasis was dogmatically condemned by the Fifth Ecumenical Council and that the possibility of eternal, irrevocable perdition is the doctrinal teaching of the Orthodox Church. Not surprisingly Hilarion now espouses a free-will, nonretributive construal of damnation.

He does not break any new ground in these chapters nor advance the discussion. His presentation of the 15 anathemas attributed to II Constantinople is particularly weak. He simply ignores the historical scholarship that has called into question their conciliar authority. Fans of Origen will be particularly disappointed that Hilarion simply assumes that Origen himself taught the system against which the anathemas are directed, once again ignoring the scholarship to the contrary.

Hilarion also ignores the biblical scholarship on the meaning of aionios in the New Testament and simply reiterates the traditional view that the NT references to aeonic punishment refers to eternal punishment. Quite honestly, Connie, your brother would destroy him in a debate on this subject.

It is disappointing that Met Hilarion appears to have retreated from his earlier enthusiasm for the eschatology of St Isaac and adopted what may be considered the conventional Eastern Orthodox view of the Last Things, which he now believes to be the infallible, irreformable teaching of the Church. Once one pulls the infallible dogma card, there’s not much possibility of constructive discussion.

Having said this, I need to mention that Hilarion still leaves open the possibility of eternal salvation in a qualified ascetical hope. Citing the famous story of St Antony and the tanner, he comments:

Hilarion’s conclusion, I know, will not satisfy you. It does not satisfy me.

LikeLike

Father,

You wrote, “He still acknowledges that an individual’s destiny is not definitively settled until the future coming judgment,” So, that means he is open to the possibility of post-mortem repentance then? Is this how he reconciles the Orthodox Church’s prayer for those in hell on the eve of Pentecost?

Also, did he offer anything new on Christ’s descent into hell? From what I’ve read, the majority of early church fathers believed that Christ presented the Gospel to both the righteous and impious dead during His descent. Some believed and followed Him out, others did not. And a few of the early church fathers even believed that Christ redeemed and rescued everyone out of Hell during His descent. To my mind, it would seem a bit unfair if this opportunity was only offered to that segment of humanity which existed before the Incarnation, and not after. Thoughts?

And what does the Orthodox Church currently teach regarding Holy Saturday?

LikeLike

Ryan, yes Hilarion still acknowledges the possibility of post-mortem salvation: “changes for the good are possible in the fate of any sinner found in Hell” (p. 557).

Though I have read Hilarion’s book on Christ’s descent into Hades, I have not yet read his discussion of this subject in his big book.

LikeLike

That is disappointing to hear. Ecclesial authority remains a vexing issue. The Protestant option manifestly ends in anarchic fragmentation. I don’t think one can jettison Tradition and have a coherent understanding of Christian truth. Nonetheless, to be candid, I believe the Christian reality is ontological and mysterious and always asks one to go far beyond a kind of catechetical understanding.

When it comes down to an assessment of eschatology and destiny and what could answer the desire implanted in the human heart, I refuse to believe that I could imagine something better, more interesting, more charitable than what God has planned for us. Something less than Christian universalism, in my view, something less than the making new of the entire cosmos, is less than I can imagine.

This is not an argument, of course; more an existential protest, but I stand by it.

LikeLike

Dear Father Aidan,

I don’t believe that Bishop Hilarion has actually changed his position. I remember several years ago on a Catholic-Orthodox blog (Eirenikon, I believe), one of the Orthodox contributors called into question the authenticity of the Brock translation of St. Isaac because of its clear espousal of universalism. Someone else then brought up Bishop Hilarion’s talk given at the World Eucharistic Congress in which he explained the thought of St.Isaac on the Divine Mercy. Many of the bloggers asked how it was possible that an Orthodox bishop, such as he, could espouse the thought of St. Isaac. The next day, when I returned to the blog, I found responses by the Archbishop himself. He stated that what he was expounding was the thought of St. Isaac, not his own thoughts. At the same time, of course, one was left to wonder. His apparent enthusiasm for St. Isaac would seem to indicate otherwise.

Nevertheless, when I read “Christ the Conqueror of Hell”, it became apparent that Bishop Hilarion’s universalism is similar to that of Bishop Kallistos and to Von Balthasar. It is one of hope. What he states in “Christ the Conqueror of Hell” does not seem very different from what you have described above with the exception of one item. On p. 192, he quotes from the troparia of the canon of Matins for Great Saturday:

“Hell reigns, but not forever, over the race of mortals; for you, O Mighty One, when placed in a tomb, shattered with your Life-giving hand the bars of death, and proclaimed to these who slept there from every age no false redemption, O Saviour, who have become the first-born of the dead.”

The Archbishop then goes on to say:

“How should we understand the words, indicated above in italics, which declare that the reign of hell is not eternal? Can we see in them an echo of the theologoumenon on the finiteness of hell’s torments, expressed in the fourth century by Gregory of Nyssa, or does it say that hell, unlike God, is not eternal since it appeared as something ‘introduced from the outside,’ foreign to God and therefore subject to annihilation? Again we stand before questions to which there are no single, easy answers. The services of Great Saturday raise the curtain of a mystery that cannot be solved. The answer to this mystery will be revealed only in the kingdom to come, in which we will see God as he is and in which God will be ‘all in all.’ ”

Is what Bishop Hilarion now says inconsistent with the above quotation?

Ed

LikeLike

Huh. Oddly enough, Ed, I seem to remember that, too. I used to occasionally frequent Eirenikon, and I think I know exactly which post you’re referring to. That was awhile ago – maybe a year or two.

LikeLike

Ed, I think that Hilarion has definitely changed his mind. I quoted him in my earlier article on the 5th Ecumenical Council: “There is also an Orthodox understanding of the apokatastasis, as well as a notion of the non-eternity of hell. Neither has ever been condemned by the Church and both are deeply rooted in the experience of the Paschal mystery of Christ’s victory over the powers of darkness” (The Mystery of Faith, p. 271). I do not believe he would write this now. But I suggest that you read the relevant material in his new book and compare. Technically, perhaps he still leaves open the possibility of universal reconciliation, but it can hardly be described as a hope—certainly not a hope that can be preached.

LikeLike

FYI, Met Hilarion’s comment on Eirenikon can be found here: http://goo.gl/nyNcXd.

LikeLike

Apparently Met. Hilarion, in the quote I posted above, is making a direct quote of St. Isaac’s. At least this part of it is: “God does nothing out of retribution. Even to think that way about God would be blasphemous. Even worse is the opinion that God allows people to lead a sinful life on earth in order to punish them eternally after death. This is a blasphemous and perverted understanding of God, a calumny of God.” http://www.orthodoxytoday.org/view/gods-mercy-the-focus-of-eastern-western-church-understanding I would like to know the rest of the quote by St. Isaac but I’m too ignorant to know where to find it.

It is very disappointing to hear what Met. Hilarion is now saying but at least we still have St. Isaac. He must be a comfort to many.

LikeLike

Connie, the quote from St Isaac that you mention on retribution is from Homily 39 of the second part. I quote it, from Sebastian Brock’s translation, in this article: “Love and the Punishment of Evil.”

LikeLike

Thank you Fr Aidan.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan,

I have been a reader of yours for months now, and I wonder if you might let me ask you a question.

Are you writing a book on apokatastasis? You’ve written so well on the subject, and I would certainly enjoy a full and scholarly treatment of it at your hands.

Dan O’Brian

LikeLike

No, Dan, I have no plans to write a book. I simply do not have the competence. I wish I did. But thanks for the compliment.

LikeLike

With apologies for the vagueness and unlearnedness of what follows! I think I have seen recontructions of Origen’s thought (e.g., by Hans Jonas?) that in some sense posited the problem of ‘aeons’ and restoration, in the sense that if there could be a Fall from the first state, why could there not similarly be a Fall from the restored state, producing a new, analogous ‘aeonian’ cycle? Or is there envisaged by Origen a perfect actualizing of potential, such that restoration accomplished is final? Is this an ‘area’ where we do not know exactly what Origen thought possibly due to the paucity of what survives?

I think I have seen suggestions by self-describing Orthodox which perhaps correspond to MacDonald’s exegesis of God as ‘Fire’: the experience is of the Aionion as Eternal, but only as tormenting and punishing insofar as one resists, clings to sin, and so on – the Hellish experience need not be (so to put it) ‘creaturely co-eternal’. (Whether is can be, is another ‘question’: does creatureliness included the possibility of the created person ‘accomplishing’ ‘eternal torments of hell’ personally in practice?)

Could St. Justinian’s questions be treated as actual rather than rhetorical? As (in effect) eliminating misconstructions, while being open to the possibility of a true formulation?

Do you, or do any readers, know of examples of Patristic attention to ‘temporary returns from the dead’ (so to describe them) such as those of St. Lazarus, Jairus’s daughter, the widow’s son, and Dorcas, and the ‘matter’ of the fixity or alterability of the will in articulo mortis and after?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fr. Aidan,

I know you question the Anathemas of the 5th Council but universalism was rejected by the 6th Council when it endorsed the Synodical Letter of St. Sophronius of Jerusalem:

“We have also examined the synodal letter of Sophronius of holy memory, some time Patriarch of the Holy City of Christ our God, Jerusalem, and have found it in accordance with the true faith and with the Apostolic teachings, and with those of the holy approved Fathers. Therefore we have received it as orthodox and as salutary to the holy Catholic and Apostolic Church, and have decreed that it is right that his name be inserted in the diptychs of the Holy Churches.” (Session XIII: Sentence Against the Monothelites)

Here is portion of interest from St. Sophronius’ Synodical Letter:

But we, because we have been given to drink the rational and guileless milk (1 Pet. 2:2) of right and blameless and well-disciplined faith, and have tasted the good word of God, thrust away all their shadowy teachings. Being free of all their lawless babblings and walking in the footsteps of our Fathers, we both speak of the consummation of the present world and believe that that life which is to come after the update present life will last forever, and we hold to unending punishment; the former will gladden unceasingly those who have performed excellent deeds, but the latter will bring pain without respite, and also indeed punishment, on those who became lovers of what was vile in this life and refused to repent before the end of their course and departure hence. For their ‘worm will not die’, says Christ the Judge, who is the Truth (Jn. 8:46), ‘and the fire will not be extinguished’ (Mk. 9:48). These things are what we think and believe, most wise one, because we have received them from the proclamation which is from the Apostles and Evangelists, from the Prophets and the Law, from Fathers and teachers, and we have made them manifest to you, all-wise one, and have hidden nothing from you. (Synodical Letter 2.4.4, Sophronius of Jerusalem and Seventh-Century Heresy trans. by Paul Allen)

I’m not trying to convince you, I just think that eternal punishment is an Orthodox dogma.

in ICXC,

Maximus

LikeLike

Maximus, I’ve been ruminating on how best to to respond to your several comments. So far, you have engaged me at the level of dogma: universalism is heresy because the Church has dogmatically defined the possibility, if not the actuality, of eternal, everlasting damnation. Case closed. The Church has infallibly spoken.

Needless to say, I find this claim dubious. It hinges on the belief that the bishops of the Fifth Ecumenical Council gathered and duly considered all expressions of the universalist hope (including the teaching of St Gregory of Nyssa) and then dogmatically rejected them. As I have shown in my article “The Heresy that Never Was” there are compelling reasons to doubt this version of events. This crack in the dogmatic door is all I and others need. We are free within the Orthodox Church to present our biblical and theological arguments for the universalist hope, and you are free to engage, critique, and reject these arguments. Perhaps one day the Orthodox Church will find it necessary to dogmatically settle the question—or perhaps not. That’s how the development of doctrine works.

I suspect, though, that the real issue between us is the hermeneutics of dogma. When and how does a teaching become infallible dogma? How do we interpret dogmatic statements? How do dogmatic statements control the future theological reflection of the Church? etc. Unfortunately Orthodox theologians have not given these questions a great deal of thought. They have spent enormous energy denying the Roman claims of infallibility, yet they have hardly begun to reflect on the hermeneutics of dogma. The irony is that this vacuum has left some Orthodox free to assert a maximal understanding of infallible dogma that far exceeds that of Rome’s.

LikeLike

Protestants, as well, have their own version of infallibility. To suddenly be without it can cause panic. How does one ensure one’s salvation without a fixed, external, inerrant, and objective measuring-stick of fidelity?

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan,

A positive and ardently held belief in universalism is not merely “heresy because the Church said so in Council”. It’s just not what’s been passed down, it’s not part of the Apostolic deposit, plain and simple. Just like Christ is not God merely because of the Creed of Nicea 325. Hope is one thing, but I’ve read where you said your view is beyond the hope of people like Balthasar. I can see that your apologetic requires that one hold to an idiosyncratic view of a minuscule minority of those within the Church, that the Greek Fathers didn’t know Greek better than a contemporary scholar, and that the Latin Fathers missed the whole point of Christian eschatology because of St. Jerome’s poor translation and exegetical skills. One must also hold that the Orthodox consensus of what occurred at the Fifth Council is also wrong. That it never even happened and that no heresy ever even existed.

It seems like you’ve come to a conclusion and now you’re supplying yourself with corrobative data by many incredible reaches. The other (standard) view, held by 98% of the Fathers is just too obvious. Fr. Aidan, this will be my last comment, you are a priest of the Orthodox Church and I’m really taken aback that we are even having this conversation. Thank you for the dialogue.

in ICXC,

Maximus

LikeLike

But at the level of gospel, we must ask, What kind of faith does the threat of eternal damnation generate? Does faith based on fear save?

This seems to me to conflate two different questions. To say that fear of damnation is a significant motivation for repentance is an entirely different question from saying anything about what faith is based on. Indeed, it doesn’t even imply that fear of damnation is a motivation for repentance rather than hope of everlasting life; it seems reasonable enough to say that fear can only motivate to repentance if one also has hope of some possibility other than what one fears. Certainly nothing Justinian says requires that anyone’s faith be based on fear of damnation, only that without it there is a danger of being slothful and going through the wide and broad gate leading to destruction.

LikeLike

Brandon, I don’t have an immediate response. I do not yet see the conflation you suggest, as it seems to me that the threat of damnation (i.e., the preaching of law) generates a different kind of personal response from the hearer than the preaching of salvation as unconditional gift (see my “Proclamatory Rule of the Gospel“). I need to ponder further on your comment.

LikeLike

To take an analogy, it’s like taking people who are drawn back to the faith because their life seems to be collapsing without it and claiming that their faith is false and based on fear of personal consequences rather than God’s love, since clearly life disasters generate a different kind of personal response from people than preaching of God’s love. (The analogy is quite exact; hell is just life disaster taken to the absolute limit.) The latter doesn’t explain anything about the conclusion being drawn; it’s too vague, and fails to take into account that nobody need deny that the ground of faith is God’s love, since what is being considered is not the ground of it but the occasion for coming to it. Occasions and grounds are not the same; or to put it in other words, the destination and the route to it are not the same thing. Some routes may make for better travel for various reasons; but it would be a mistake to think that this in and of itself tells us anything about the destination. (Arguably a point Justinian himself is making, that people need something that will remind them that ease of travel is not a particularly important factor here.)

LikeLike

I think Brandon’s point is that our concern for self-preservation isn’t an evil (at worst) or illegitimate (at best) motivation for believing the gospel. Indeed, without that existential drive, faith might be inconceivable. Take Ziziouslas, for example. He plays this existential drive up as God-given, and rightly so. Creaturely being just is this existential search (for identity, meaning). It’s hard to see how the desire for such identity (true personhood) and its permanence/preservation is graciously God-given but the attending ‘disfavor’ for the suffering of failed personhood (false selves) be itself a bad thing. If the desire is God-given, and if our searching and choosing are part of creaturely becoming, then we can’t dismiss the drive to flee the existential despair associated with falsely identifying ourselves.

That said, a couple things: (1) we humans have a talent for perverting everything, so it doesn’t surprise me that one could actually misrelate to a God-given process and turn the relief that gospel brings from the pain of existential despair into yet another ‘false self’ (and God just another ‘idol’), and (2) I think the perfecting of desire means the ‘disfavor’ (or fear, or other pain-centered forms of motivation) associated with our false selves means such motivations are finally effaced by contemplation of the Beautiful (the beatific vision) and God *alone* becomes our all-defining desire without requiring any motivation from despairing alternatives. In fact, this is just what I take the gospel’s ‘end’ to be—God alone becomes reason enough. The despairing alternatives are like the separate parts of a fuselage on a rocket. They’re helpful initially to overcome the world’s gravity, but eventually they separate and fall back to earth while you move on.

LikeLike

tbelt,

You may be familiar with this, but I have read quotes from the Fathers to the effect that fear may quite well be the impetus for many souls to commence the search for salvation (as escape from punishment), but it cannot actually effect our salvation or bring it to completion, which depend rather upon the love of God. Only love can do the latter.

LikeLike

I’d agree Karen. I didn’t mean to suggest that ‘fear’ is in some sense an expression of faith or a participation in salvation. I like your word ‘impetus’. I think we all are aware, however, that many believers are an odd mixture, i.e., they continue to be defined by fear throughout their journey of faith.

LikeLike

tgbelt,

Yes, it’s hard not to be aware that believers are “an odd mixture” of faith/love and fear, since that pretty much describes me, too. 🙂

LikeLike

What does it mean to say that universalism is condemned by the Church? To simply state this, without any specifics is, I would think, rather meaningless. Surely all Orthodox and Catholic believers hold that Christ came into the world to save all mankind. So, does the so-called condemnation of universalism mean that it is impossible for Christ’s mission to be successful? If so, that would be a very odd thing to enshrine as dogma. Nevertheless, I think this is precisely what some profess to be the case. They believe that it is a dogma that some people, perhaps most people will end up in eternal misery. They believe this on the basis of certain texts of scripture interpreted in a particular way.

When Father Aidan makes the point that “aionios” does not, in itself, mean “eternal” or “everlasting”, he is countered by the fact that Justinian and many saints after him did take it so and therefore, the case is closed. But if “aionios” clearly means “eternal”, how do we explain the fact that none of the early anti-Origenists ever criticized his doctrine of apokatastasis as regards human beings? How do we explain St. Gregory of Nyssa’s universalism or St. Gregory Nazianzen’s strong leanings in that direction? Were these saints simply unable to understand the clear words of Scripture? This is very difficult to believe. Indeed, the tradition in which St. Isaac of Nineveh was nurtured, having taken no part in the 5th Council, could still hold to the earlier tradition that “aionios” or “olam” did not normally mean “eternal.” One need only look at the “Book of the Bee” to see that this idea continued on in the Assyrian Church of the East well into the 13th century.

Certainly it is correct to condemn the notion that salvation is automatic and that man need not cooperate with God’s grace in order to obtain it. But why would anyone want to condemn the notion that God is working for the salvation of all and that we can hope and trust, with some confidence, that He will obtain what He desires?

LikeLike

Well said.

LikeLike

Indeed, as AR noted, very well said.

There’s a kind of rigid fundamentalism within every church: Evangelicals, Catholics, Orthodox, all possess that type. I think we are called to tolerate them in charity, but I don’t find such views at all consistent with the deepest understanding of the Gospel.

LikeLike

“deepest understanding” – yes, that’s a good phrase.

LikeLike

Hope is the twin virtue of Faith – Love is the parent of both. It’s odd that there’s a subtle denigration of Hope that creeps into some of these conversations. Faith by itself is simply belief that God is. Hope is expecting good things from him rather than evil. In both cases, they are produced by Love because when God’s Love dwells in us, we have in ourselves the evidence of the nature of reality – that it is substantial and that it is good and that it is eternal.

“Now abides Faith, Hope, and Love, but the chief of these is Love” for “Love believes all things; Love hopes all things.”

LikeLike

AR: You should find a copy of Charles Peguy’s The Portal of the Mystery of Hope.

Peguy and MacDonald are two of the best at portraying the loving Fatherhood of God.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, I will.

LikeLike

Respecting Maximus’s decision as to having made his “last comment” (meaning one will have forensically to contruct a ‘position’ that might represent ‘his’), I wonder whether one must read the 6th Council endorsement of St. Sophronius’s letter as if it had said ‘this is the only possible Orthodox understanding’ or whether one can read it as meaning ‘this is a possible Orthodox understanding’?

Might one compare, though to the possible dismay of countless Orthodox, the bull Grave nimis of Sixtus IV in 1483, in which the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin was held as possible of belief, and its rejection equally as possible of belief, with neither as necessary of belief – which situation pertained for the next 366 years – and which I have read effectively still pertains for Orthodox quite apart from Grave nimis?

Is the matter possibly that eternal torment is possible of belief, and the salvific end of any and all torment is equally possible of belief?

That the Church has not, and so one must not, dogmatically pronounced exclusion of either possibility?

Can anyone suggest, historically, what, if any evidence, there is of some such situation being explicitly addressed and explicitly rejected, on Ecumenical Conciliar level?

Maximus (I do not say, unusually) would seem to take what he quotes as exclusive endorsement of eternal torment, and, consequently, simultaneously, inseparably, “universalism […] rejected by the 6th Council when it endorsed the Synodical Letter of St. Sophronius of Jerusalem”. But, is it?

LikeLike

I would note that the fathers at the Council of Chalcedon endorsed the Letter of Ibas: “We have read his letter and find him to be orthodox.” The Letter of Ibas was one of the Three Chapters condemned at the 5th Council. So which council was right? Hmm…

LikeLike

Fascinating post and discussion. I hope and expect that the last word hasn’t been spoken here.

The letter itself raises some good points (the 2nd one being the most challenging one IMO) but there are certainly compelling answers to those questions, and I’m not sure what the letter itself actually purports to prove. Each of those 4 points really deserves it’s own discussion. I also wonder, how exactly were the later saints who held to some form of universal reconciliation ever recognized as saints in the first place? No doubt that these later saints were aware of the supposed dogma of everlasting conscious punishment – why is it that they didn’t recognize it as dogma and instead believed either annihilation or universal reconciliation?

Not being Orthodox myself and given several of the comments, I have to ask – is Orthodoxy capable of an honest discussion in this area or any area? I don’t mean to be rude or disrespectful in any way – it’s a serious question about the nature of dogma and Tradition in Orthodox thought and life. It seems that the emphasis from Orthodox detractors in any area of disagreement is to simply (selectively) quote Tradition and the Fathers – never a need to engage with any argument itself since the heavy lifting has been done. If so, that’s fine – but it’s important to acknowledge that working paradigm.

Orthodox Tradition seems very specifically defined and it’s authority VERY closely guarded. If “the Holy Spirit guides and enlightens her Saints in Holy Tradition”, to quote Maximus, would it be reasonable to expect all of the Saints to agree in matters of dogma? This kind of theological agreement across space and time obviously doesn’t exist, so why is that?

If simply stating what the majority view was at a given point in time is enough to settle the issue once and for all, there simply is no point in any kind of dialogue. If all that matters is what the Fathers believed, one is left picking the Fathers that agree with them and silencing or explaining away the ones that they don’t or pretending they don’t exist (EXACTLY like us Protestants do with the Bible). So it seems like any dialogue in which one questions the dogma of Holy Tradition would seriously cripple this Orthodox theological foundation. Am I reading that correctly?

LikeLike

“Not being Orthodox myself and given several of the comments, I have to ask – is Orthodoxy capable of an honest discussion in this area or any area? I don’t mean to be rude or disrespectful in any way – it’s a serious question about the nature of dogma and Tradition in Orthodox thought and life. It seems that the emphasis from Orthodox detractors in any area of disagreement is to simply (selectively) quote Tradition and the Fathers – never a need to engage with any argument itself since the heavy lifting has been done. If so, that’s fine – but it’s important to acknowledge that working paradigm.”

Mike, you raise an important question. If one were to restrict one’s knowledge of Orthodoxy to those of us who comment and argue on the web, one might well conclude that Orthodox theology was simply a matter of quoting authoritative dogmas and authorities. Catholicism has its own version of such a degenerate theological method. Karl Rahner called it Denzinger theology. Theology and dogma are reduced to a static set of propositions.

But if Orthodox theology is apophatic and eschatological, as I think and hope it is at its best, then the very acknowledgement that our theological formulations cannot fully articulate divine truth, that divine revelation cannot be reduced to propositions, then it seems to me that an Orthodox theologian must always be ready to explore further. All truth is God’s truth. There cannot be anything to fear from discussions with non-Orthodox theologians or with scholars from non-theological disciplines. I don’t, however, think we are very good at it yet.

Dr George Demacapoulis has recently raised concerns about what he calls Orthodox fundamentalism.

But Orthodoxy does insist on her dogmas, formulated by ecumenical council under the guidance of the Spirit, that guides and governs her theological reflections. She does not pretend to come to the Scriptures, for example, as a blank slate. The dogmas are the grammatical rules by which she reads the Scriptures rightly. It might be possible to reformulate a true dogma, but we cannot abandon them. Hence we do not each generation ask ourselves “Is God really trinitarian?” or “Is Jesus really true God and true man?”

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughts and explanation Fr Aiden.

Regarding dogma, certainly (most) Protestants respect the early creeds and aren’t looking to reinvent the wheel on essential doctrines. But there is always confusion over what is dogma/essential/non-negotiable and what isn’t as I’m sure you’re well aware.

I’m used to Protestant biblicism (driven by the myth of the blank slate / plain reading) where it’s common to prove doctrines by lobbing verses at one another like grenades. The verses could be very obscure and it ends up getting quite ridiculous and nasty at times and is distracting from Christ. I didn’t expect to see some of the same thing from a different perspective – just substitute Fathers and Church councils (sometimes obscure councils or rulings, etc) in the place of the Bible. Again, forgive my ignorance here – I haven’t much familiarity with the Orthodox tradition outside some of the basic differences with the west.

LikeLike

Mike, here’s a passage from Met John Zizioulas which I think represents how many Orthodox understand the function of dogma in the Church:

LikeLike

There’s a critique of Dr. Demacapoulis’ argument here: http://fatherjohn.blogspot.gr/2015/02/response-to-orthodox-fundamentalists-by.html

It seems to me the rather nebulous and vague nature of Dr. Demacapoulis’ assertions invite such a critique (and expose the weaknesses in his position).

LikeLike

Oh my goodness, I couldn’t even finish reading that load of.. blighted nonsense. If Dr. Demacapoulis’ assertions are vague, which is natural given the platform, Fr. Dwight’s are a very shallow reading of history. It completely ignores the facts that

1) To this day there is a whole movement of Christians who think of themselves as, and call themselves, fundamentalists. They have institutions, one of the better of which educated me, and they have a long-standing online conversation going on, the catchphrase of which is, “A Fundamentalism Worth Saving.”

2) Before fundamentalism was applied to Islam, the New Evangelicals split off from the fundamentalists, taking many of their assumptions with them but seeking a more compassionate and relevant image. The New Evangelicals are the previous generation of those people who, today, simply think of themselves as Evangelicals. Since these people dominate American religion and conservative politics, it’s really, really ill-informed to imagine that American fundamentalism doesn’t exist any more.

3) There’s a reason for tracing similarities between Islamic and Christian fundamentalism, and they aren’t all political. It’s because there’s a similar approach between the two to each religion’s sacred texts.

If he can’t get anything out of critics’ use of the word “fundamentalist” except “stupid” that’s… a very fundamentalist inability.

LikeLike

I think you meant Fr. John (not Dwight)? Good points about the realities of American fundamentalists and their self-identification.

I agree with you about point 3 (and this is certainly a parallel Dr. Demacapoulis could have elaborated on to show how some Orthodox are treating their texts/sources this way as well). Fr. Stephen Freeman does a lot of good work demonstrating this parallel between American Christian fundamentalism and Islam. But I don’t necessarily think this is why American Fundamentalists and Islamists tend to be lumped together in major secular media presentation, which is much more political, and the latter is likely what Fr. John had in view. Whether he should have focussed on this secular use, or not, given the intraOrthodox context, is another question.

I still found Fr. John’s critique of Dr. Demacapoulis’ setting up of straw men and use of hyperbole had some weight for me. Can you elaborate on what you mean by “given the platform”? (I can be a bit slow on the uptake.)

LikeLike

Karen, somehow I transmuted Whiteford to Dwight… I have had to look at it three times just to type it here. Isn’t that odd? Perhaps it’s because I’ve never known anyone by that name.

In regard to your first question, I go back and forth between two views on how much weight we should give to critiques of the Christian community from outside. On the one hand, judgment must begin at the house of God. We look silly and worse every time we let outsiders force us to deal with our issues rather than being zealous to see and deal with them ourselves. On the other hand, the media is full of people who simply want to win points and gain readers, and don’t care how.

About the platform… I’ll try to make my overall point more clear. I don’t think vagueness is a weakness when writing a blog essay – just a limitation. In Dr. Demacapoulis’ case, he is speaking within the context of a well-developed tug-of-war within the Greek Church and basically stating his position within that debate and giving his reasons for why he falls on that side and not the other. Thus he dwells on his concerns rather than on arguments or on naming names, which would be impolitic. In the case of Fr. Whiteford, he is being specific but that specificity becomes a weakness when he misinterprets a history he doesn’t understand – in which case I would prefer vagueness and personal concerns.

I shouldn’t imply, and don’t want to really, that you “should” know this or see it this way. Obviously this is a matter of personal concern to me which means both that I know more about it than the average pew-sitter and that I’m more easily touched off on the subject.

***

In addition to all this, I’ve been thinking about the overall subject through the week, and I’m developing an understanding of fundamentalism as something that was invented to replace orthodoxy and which therefore militates against it while seeming to defend it. If you think about it, the Protestants who invented fundamentalism did so from within a situation in which everyone already knew what the orthodox positions were on these questions, but there were many intellectual challenges to the faith and many people were fudging on that orthodoxy or trying to reframe it or even just walking away from it. So it’s not that fundamentalism added orthodoxy back into the mix. Orthodoxy never disappeared. It was designed, rather, to bring people back to orthodoxy and therefore was something in addition to orthodoxy.

What was it for, then? Simply put, it was an attempt to nail down to orthodoxy the consciences of people who otherwise might stray from it. This was ill-considered because it produced a spiritual disease in which the conscience had to bear the load that the intellect was unable to bear. Thus, the fundamentalist conscience always was and always is slavish. It is enslaved to pre-determined ideas which cannot do a person any good unless he arrives at them by a different route – that is, freely and with understanding and good faith. And since the judgment is enslaved to the conscience, it accepts all sorts of foolishness in addition to the orthodoxy that fundamentalism was intended to enforce. Because this conscience is willingly enslaved, it constantly seeks others to pull into the same orbit, and so the burden of a fundamentalist’s song is always the constant attempt to nail down the consciences of other Christians as much as possible.

The intellect is then put to work defending the dictates of the conscience. In this way, the whole spiritual man is thrown out of balance and the intellect and the conscience, as well as the moral being, are not allowed to mature.

Why do people bear up under this? Because of the constant terrors and threats that assail them. Terrors of being the last person to believe the orthodox position, and not being able to hold on to it, and consequently being damned. Threats of summary banishment from the enslaved community, which constantly judges the words and actions of others to make sure they are holding to the fundamentals and all the hedges and fences and standards and measures which the diseased conscience piles up in order to protect those fundamentals.

LikeLike

AR, That was a productive week’s thought, I’d say! You certainly have an excellent head on your shoulders, and you have a real knack for putting your observations and convictions into words. You could write a book about the “fundamentalist conscience”, which I expect would benefit many.

I appreciate the clarification about not intending to “should” on me (as I sometimes put it!), and I completely understand getting set off by comments or posts on certain subjects as a result of one’s personal experience. It’s the same for me, of course.

As I’ve mentioned elsewhere, my experience with fundamentalism is much more oblique than yours (i.e., not from my childhood or parents). My parents moved from mainline Methodism, through Evangelical Presbyterian to conservative “undenominational” low-church Evangelical (the last two when I was already an adult already mostly out of the nest). I have great affection for my childhood church. During that period, most of the lower clergy and laypeople remained quite orthodox, yet were not legalistic or biblicist about it, while many bishops were already well along the slide into liberalism. It grieves me to see how liberalism has basically made that denomination today one of the many sites of our culture’s spiritual wasting disease–basically a baptized (if you use the term rather loosely) cultural status quo. Perhaps this is why I have a higher tolerance for hearing critiques from Orthodox of a more fundamentalist bent, because I can appreciate the strong desire to keep the connection to genuinely orthodox content and to highlight and emphasize this content, even if I, too, get uneasy when the emphasis on the “what” of orthodoxy threatens to eclipse the “why”–subtly, or not so subtly, seeking to dominate and subdue the conscience and bring it into bondage without first properly engaging the intellect/nous.

I admit to being mostly ignorant about the various forces in the Greek Church (certainly completely so from the perspective of personal experience).

LikeLike

My son reads from the scriptures every day, aloud to me, as part of his homeschooling routine. Today he read from Wisdom of Solomon 7. It speaks of a personified, feminine (!) Wisdom. From verse 27: “…and in every generation she passes into holy souls and makes them friends of God and prophets.”

For Orthodox Christians, this should temper strict ideas about scriptural inerrancy. If inspiration happens by the prophet’s acquisition of holiness and wisdom instead of by God sort of taking their minds over while they write, it is possible to conclude that prophets differ in the extent of their understanding and holiness, and therefore different scriptures differ in the extent of their penetration into God’s mysteries.

For example, the wisdom that guides one prophet to conclude that God’s justice ends with the wicked souls meeting the eternal flame, may take another prophet further.

Also, we see the phrase, “In every generation.” In contrast, fundamentalism inevitably assumes that God has spoken his last word on every subject, and that however mighty other generations may have been in prophecy, we are relegated to the position of slaves who must bow before their absolute statements.

LikeLike

AR, this is SO good! It addresses to some degree my questions I just posted above.

LikeLike

Oh, good! I’m glad to hear it, Connie. It was also encouraging to me when I heard it read.

LikeLike

“Orthodox Tradition seems very specifically defined and it’s authority VERY closely guarded. If “the Holy Spirit guides and enlightens her Saints in Holy Tradition”, to quote Maximus, would it be reasonable to expect all of the Saints to agree in matters of dogma? This kind of theological agreement across space and time obviously doesn’t exist, so why is that?”

You’ve definitely picked up on the way a lot of people think about it. However, the saints did NOT all agree on everything, and therefore one is left with two possibilities. One can either develop discernment, which involves paying attention to arguments and distinctions, whole truths and connections (among other things) and especially, demands that an Orthodox Christian be not just a venerator of the Church, but must be the Church; not just a respecter of her authority, but a wielder of her authority. In other words, one must reach adulthood, even spiritual parenthood, in the Church.

I imagine that it’s not much different than the things T. S. Eliot said about the artistic tradition, which are worth paying attention to… only when one is standing in the stream of a tradition can one know with certainty where it is flowing next.

The other option is simply to try to figure out the majority opinion on every question. I, for one, balk at the ignoble implications of this possibility.

I believe that the Holy Spirit enlightens each one of us – that’s the whole point of chrismation. Presumably a person who has been canonized had a clearer experience of that in the flesh but there’s no assumption that every saint had a whole experience of that enlightenment or, certainly, that every canonized person had a clearer experience of that enlightenment on every question than someone now living. This is especially true of political canonizations.

Many people who convert from the uncertainties of Protestantism come to the Orthodox church scalded by the intense way that Protestants tend to experience the epistemological crisis,and they are often attracted by exaggerated or simplistic representations of how we get our doctrine here. Then, they (we) are understandably discomfited when we run across a discussion in which it seems as though all that Athanasius-vs.-the world stuff is still going on, in new arenas.

I think Fr. Kimel responds to such discomfiture splendidly.

LikeLike

That seems to me well said, AR. I agree with you about Fr. Aidan, too.

LikeLike

Thanks for your thoughtful response AR.

I don’t think there’s any way to avoid some level of discernment or some degree of uncertainty and mystery. For better or worse it’s part of being human.

For my part, my original post was just an observation about the degree to which I see references to seemingly obscure church council documents that 99% of the world has no idea even exist, but are referenced as authoritative and infallible. New territory for me. This isn’t meant to be disrespectful at all – I was just surprised to see one perspective in the conversation focus exclusively on the authority of a specific letter while seeing no need to address the content of the letter itself or the other authoritative figures that might be at odds with aspects of that content.

LikeLike

Oh, I didn’t take it as disrespectful at all. 🙂 I think you’re picking up on inconsistencies within the Orthodox experience that I am even more interested in understanding, perhaps, than you are!

LikeLike

And I like that TS Eliot reference – about the need to stand in a stream to know where the stream is flowing. Both strike me as true – both that “stream” is an appropriate metaphor and the need to be in that stream in some way.

LikeLike

The Roman Emporer, Justinian, was not a saint! He, along with Augustine and others are largely responsible for teaching and establishing the erroneous heresy of an “everlasting” hell, and using the “Doctrine of Reserve” for justifying its use for the Roman State Church.

LikeLike

Ronald, the Emperor Justinian is indeed regarded as a saint by the Orthodox Church and is commemorated on November 14th.

LikeLike

After reading what transpired during his reign as emperor, and his condemnation of “Apocatastasis”, you will never get me to agree that he was a saint–I don’t care what the Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox churches state about him.

LikeLike

Well, Augustine is a favorite whipping boy for the Orthodox, and I certainly find his views on hell disagreeable. Yet as someone largely formed by the Catholic tradition, there’s more to Augustine than that. He had many talents and insights that were beneficial to the body of Christ.

Also, you do realize that Catholics in the West often see a pretty close relation between Orthodoxy and political regimes? That kind of mutual “xenophobia” benefits no one.

LikeLike

It seems to this lay Renewal Protestant that Roman Magisterium, Protestant Bible inerrancy/infallibility, and Orthodox Patristic synthesis can all suffer from over-simplification and over-emphasis. Isn’t that a good working definition of most heresy?

LikeLike

I hope to do some posting on the question of dogma and theologoumena in the next couple of months; but before I can get to it I need to write my series on St Gregory’s Life of Moses and two book reviews.

LikeLike

I have not yet begun your Life of Moses series, but in in the comments here there is a lot of attention both to dogma and to saints: would you consider combining with, or separately complementing, your “posting on the question of dogma and theologoumena” with attention to the ‘canonization’ and/or recognition of saints?

I just read an interesting comment related to that by “ikokki” on Roger Pearse’s 3 February post on “The literary development of the ‘Life’ of St Nicholas of Myra (= Santa Claus)” at his site (q.v.).

LikeLike

Not heresy, no. Fundamentalistic tendencies, maybe. But scratch a fundamentalist and you’re going to find an over-activated conscience, which is not really a doctrinal issue.

LikeLike

Also, what is the nature of authority? Is it possible for something to be “authoritative” without being “absolutely authoritative?” Even something the Holy Spirit was involved in? It’s natural to answer that question yes when you’ve gotten used to seeing authority as related to “authorship” and “authenticity” rather than envisioning it as an unlimited and unqualified license to demand obedience.

LikeLike

… unlimited and unqualified obedience, even.

LikeLike

Great article. I’m a big fan of Bulgakov’s interpretation of the sheep/goats passage. Rather than speculating about a magic threshold that sunders the “saved” from the “damned” at the moment of bodily death, he argues that our personal balance between sheephood (disposed toward loving the “least of these”) and goathood (disposed toward neglecting the “least of these”) remains tangled and unstable unto death and beyond. No-one is entirely sheep nor entirely goat, though naturally everyone participates more fully in one category than the other. Thus, For Bulgakov, the fire that the goat-like are taught to expect is a purging fire that each and every one of us will pass through without exception (though to varying degrees of intensity). It is the fire of love made famous by Isaac the Syrian.

LikeLike

That threshold has been a problem for me, too.

Perhaps it’s like in I Samuel 22:26-27: “With the kind You show Yourself kind, With the blameless You show Yourself blameless; With the pure You show Yourself pure, And with the perverted You show Yourself astute.”

Are we then capable of seeing only those virtues in God, in which we ourselves participate to some extent? Is God, then, speaking to the goatish parts of us when he speaks of implacable ruin?

Also, I think of John 2:24-25: “But Jesus, on His part, was not entrusting Himself to them, for He knew all men, and because He did not need anyone to testify concerning man, for He Himself knew what was in man.”

I am inclined to think that people like St. Isaac and George MacDonald, to whom God appeared in such loving guise, were those rare souls to whom Christ had entrusted himself and his truth to a greater degree, because of what he saw in their hearts.

LikeLike

…their ability, that is, to see his justice and mercy for what they are.

LikeLiked by 1 person

AR, this variable capacity in each of us for discernment of the virtues of Christ is perhaps the reason these questions will never be resolved on the level of rational argument or perhaps even Conciliar pronouncements, but only in the deepest recesses of each individual heart as it becomes ever more naked and vulnerable (pure) before Christ. It seems to be the Spirit’s wisdom that in the Tradition and the Saints (collectively), the threat of of hell as a real possibility (in context of all other aspects of Orthodox teaching, as opposed to the Jonathan Edwards or Westboro Baptist presentation) must remain as our pedagogue and goad to lead or push us ever closer to Christ. It seems to me this also correlates to the insight that each of us needs different medicine to be healed. The pride and unbelief that remains in our hearts manifests as despair in some and callousness and heedlessness in others. The application of the Tradition for each to correct each one’s tendencies looks quite different.

LikeLike

Karen, are you drawing that conclusion because A) it best explains the existence of this matter in the tradition, or B) you know of people who are better off because of the threat of hell?

LikeLike

AR, this is a tentative conclusion I offer for both reasons you suggest. (Of course, I’m open to consider other perspectives.) In the context of this discussion, I find I keep coming back to the story of Abraham in Genesis 18:16-33 and his intercession with the Lord about the fate of Sodom and Gomorrah. Why did Abraham stop asking at ten righteous people? I don’t know. Maybe he was confident there were at least ten people in Lot’s household. and so he was satisfied that Lot and his family would be spared destruction, but whatever the case, knowing what he did learn through that exchange with God was enough for him. In the same way, at a given point in our own imperfect spiritual state, perhaps what we do learn from the Tradition is enough for us to trust to God’s mercy what we can’t yet know (in terms of the final outcome). I do believe, as you have suggested, what we perceive in the Tradition (and its depth) is conditioned by the nature and purity of our own hearts.

LikeLike

I can’t think of anyone I know to be better off because of the threat of everlasting punishment (if that is what we mean by Hell) than they would have been otherwise. And lots who are worse off: even ISIS believes in Hell, and believe me, Catholic Hell doesn’t hold a candle to Muslim Hell.

As for Abraham, 1) The text suggests that this plea to spare the city for the sake of ten was as far as Abraham dared to take what he saw as his audacity in addressing the Lord this way. 2) He wasn’t learning from the Tradition; he was learning from God directly and I am suggesting we need to do the same.

LikeLike

AR, there is the “threat of hell” as external manipulation by another (usually preachers) and there is the “threat of hell” as inner conviction from the Spirit. It is the latter case where I believe some are better off as a result of it. I believe there are times I am better off because I am seriously reckoning with the fact my choice to sin will have consequences which I could carry with me into Eternity. This is a teaching which helps me to sober me up when I’m being lulled into spiritual sleep. I also have heard testimonies of those who have had near-death experiences where they encountered a hell-like reality which led to their repentance and spiritual transformation in a good way.

Of course, there are others (and same with me at other times) where the threat of hell (especially the Jonathan Edwards version) is what drives them away from “God.” This was very nearly true for me before I discovered St. Isaac’s understanding of gehenna (which is how I understand hell now, though I am agnostic about how long it lasts). As you point out, not all “hells” are equal, but I believe to be an Orthodox Christian is to accept the reality of the possibility of hell in an Orthodox and biblical sense. This is not to say I believe in the external imposition of the threat of hell on another’s conscience as a regular manipulative ploy, but I do believe in the preaching of the full Orthodox faith (in which Christ’s parable of the Last Judgment is a regular and recurring theme). I don’t believe this should undercut what Fr. Al says below about also preaching the gospel as unconditional promise, and his point in this regard really resonates with me, too. The Bishop at my first parish preached that repentance doesn’t mean focussing in regret on one’s sins, but rather looking away from self altogether and focussing on Christ instead. More than anything else, preaching the gospel as unconditional promise elicits faith and this kind of true repentance.

With regard to why Abraham stopped, yes, the text implies he felt he had reached the limits of his audacity with God–but still why at ten? I suspect by that point (and precisely because of the extent of his audacity) he had gained enough of a sense of the nature of God (patient and forbearing) and God’s judgment (merciful) to set his heart at rest. Yes, I agree he was learning from his direct encounter with God. For me, seeking God directly is also intimately connected with seeking to more deeply understand the Tradition as it has been revealed in the Church (as opposed to traditions) because ultimately I expect those two to harmonize.

LikeLike

Karen, it sounds reasonable but I keep waiting to hear a distinction made that would allow me to say ‘Amen.’ As I struggle to articulate for myself what that distinction is – aside from the pain of hearing hard truths – I think I’ve located a conviction within myself. I feel that when seemingly contradictory items appear in scripture (and therefore in Tradition,) and given that such cannot both be true in the same way, one of those must be subjugated to the other – explained by the other.

Another possible approach is to tweak them so that they both seem true and non-contradictory, but I feel that this is an inferior approach. First, because it does not acknowledge the differences between the people to whom those different speeches and writings are given. Second, because it does not acknowledge the process of human consciousness, by which each generation contributes something that makes further understanding and distinction possible. Third, because some distortion must inevitably result to both truths – for instead of one essential truth guiding us to interpret another, we have our own minds guiding us to re-interpret both truths.

Therefore: what is said to brutal and tyrannical people must be understood to be a heuristic device. It must also be understood to be an inferior understanding of God’s ways than what is said to gentle and noble souls. And so that we don’t call God a liar, the first must be understood to be an expression of the same truth, vision, or insight being told to the second, but a far less enlightening expression. God will not uselessly enlighten anyone, lest they be further damned.

The possibility of hell, then, like the regret for sins, is not something for noble and gentles souls to dwell on, lest they regress to brutality. What is possible to a brutal mind is not possible to a loving heart. Not only is it not possible to dwell on, but it is not possible to attribute to God.

What can we conclude, then, but that to brutal souls God is the author of their suffering because of his inflexible goodness and love – they would have him change so that they do not have to. But for gentle souls, there is no threat from God – not because they see themselves as deserving of less punishment than others, but because they are capable of understanding that God’s hands are not at all stained with evil – because they understand that evil and hell have no ground of being and therefore cannot endure as God, as Love, can endure. It is the changeful, and not the changeless, that causes suffering.

This is why I cannot really believe what you say about yourself – that you sometimes do good because of threats. I think perhaps this is a self-deprecatory expression of the horror that good people feel, not at the punishment they may undergo for their sins, but at the evil itself which may be wrought by those sins.

I believe it is permissible to use discretion when examining the tradition – not only when choosing what to use and apply to oneself, but also when trying to understand what is greater and more pure and more penetrating in truth than the rest. This activity, in fact, may help us to better grasp the distinction between Tradition and tradition.

Here is my guide, from St. Porphyrios. It is the highest expression I have found of the truth about God and Hell.

“This is the way we should see Christ. He is our friend, our brother; He is whatever is good and beautiful. He is everything. Yet, He is still a friend and He shouts it out, ‘You’re my friends, don’t you understand that? We’re brothers. I’m not…I don’t hold hell in my hands. I am not threatening you. I love you. I want you to enjoy life together with me.'”

LikeLike

AR, I love the way you think and express these things. I don’t find anything to disagree with in what you write here. Indeed, it is a blessing to me to read it! In anticipation–blessed Lent!

LikeLike

You too, Karen. Thanks.

LikeLike

Bulgakov’s insight/interpretation of the sheep and goats corresponds with Solzhenitzyn’s that the line between chaff and grain cuts right through the middle of every human heart. It was this deep conviction in my own heart (and the same struggle with that threshold) which propelled my journey to Orthodoxy (though I had never at that point read either of these two authors).

LikeLike

Hello Father,

I hadn’t noticed the quotation from “The Mystery of Faith.” It does indeed look as though he has changed his mind. I wonder how difficult it would be to contact him and ask him his reasons for so doing. It would also be interesting to ask him about his thoughts on the recent scholarship that you’ve brought forth, both with regard to the 5th Council and with regard to apokatastasis.

Ed

LikeLike

In Met Hilarion’s book on St Isaac, he explicitly makes the point that “Isaac’s idea of the apokatastasis ton panton (restoration of all). In Origen, universal restoration comes not as the end of the world, but as a passing phase from one created world to another which will come into existence after the present world has come to its end. This idea is alien to christian tradition and unknown to Isaac” (p. 296, n. 67). Here Hilarion is sounding the argument of Met Kallistos and, at least implicitly, suggesting that the 6th century anti-Origenist anathemas do not apply to Isaac’s own construal of universal salvation. In his new book, Hilarion simply takes the anathemas at face-value, as it were, and applies them in general, totalitizing fashion. I imagine that he would argue that this is how the anathemas have been received by the Church.