[This article has been significantly revised and republished under the title “Apokatastasis and the Radical Vision of Unconditional Divine Love.]

What is at stake in the universalist/infernalist debate? Perhaps the best way to answer this is to first identify what is not at stake.

What is not at stake is the christological foundation of salvation. I wholeheartedly affirm that salvation is through and in Jesus Christ, the incarnate Son of God.

What is not at stake is the freedom of the human being. I wholeheartedly affirm that God does not violate personal integrity nor coerce anyone into faith.

What is not at stake is the preaching of repentance. I wholeheartedly affirm that the preacher must summon sinners to repentance of their sins and personal participation in the life of the Holy Spirit.

What is not at stake is the horror of hell and the outer darkness. I wholeheartedly affirm that rejection of God necessarily results in spiritual death and is thus a fate about which the preacher needs to warn his congregation.

And I’m sure there are several more “not at stakes” that I cannot think of at the moment.

So what is at stake?—the good news of Jesus Christ. In this article and the next, I’d like to highlight what I believe to be the two essential matters—the unconditionality of divine love and the eschatological triumph of the risen Christ.

The Unconditionality of Divine Love

In the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God has been revealed as love—absolute, infinite, unconditional love. In the wonderful words of St Isaac the Syrian:

In love did He bring the world into existence; in love does He guide it during this its temporal existence; in love is He going to bring it to that wondrous transformed state, and in love will the world be swallowed up in the great mystery of Him who has performed all things; in love will the whole course of the governance of creation be finally comprised. (Hom. II.38.2)

“God is love,” the Apostle John declares (1 Jn 4:8). God is Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, the Church catholic declares. The former is but the succinct expression of the trinitarian revelation given in the Scriptures. I believe, I hope, that all Christians agree with the above claim, though many disagree with the implications that the universalist draws from it. God wills the good of every creature he has made. As the Apostle Paul writes, God our Savior “desires all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Tim 2:3-4). And the Apostle John: “In this is love, not that we loved God but that he loved us and sent his Son to be the expiation for our sins” (1 Jn 4:10).

Yet while all Christians may affirm God as love, many balk at the description of the divine love as unconditional. They insist that God has in fact stipulated multiple conditions for the fulfillment of salvation, the most commonly mentioned being the free response of faith and repentance. Thus St Basil the Great:

The grace from above does not come to the one who is not striving. But both of them, the human endeavor and the assistance descending from above through faith, must be mixed together for the perfection of virtue … Therefore, the authority of forgiveness has not been given unconditionally, but only if the repentant one is obedient and in harmony with what pertains to the care of the soul. It is written concerning these things: “If two of you agree on earth about anything they ask, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven” [Mt 18:19]. One cannot ask about which sins this refers to, as if the New Testament has not declared any difference, for it promises absolution of every sin to those who have repented worthily. He repents worthily who has adopted the intention of the one who said, “I hate and abhor unrighteousness” [Ps 119:163], and who does those things which are said in the 6th Psalm and in others concerning works, and like Zacchaios does many virtuous deeds. (Short Rules PG 31.1085; quoted in Augsburg and Constantinople, p. 38)

Patriarch Jeremias II cites this passage from Basil in his critique of the Lutheran construal of justification by faith, which he interpreted as undermining the necessity of good works. His critique is well worth reading, as are the responses by the Tübingen theologians. For the Patriarch, as for so many of the Eastern Fathers, the emphasis falls not on the sola gratia, as one finds in St Augustine of Hippo and St Bernard of Clairvaux, but on the repentance that draws to us the divine mercy: “Even if salvation is by grace, yet man himself, through whose achievements and the sweat of his brow attracts the grace of God, is also the cause” (p. 42). Clearly, though, this is not the whole evangelical story. I understand such statements as expressions of pastoral care, as exhortations to devote our lives wholeheartedly to a life of holiness and discipleship; but I have also seen, and experienced within myself, the spiritual and emotional damage that can be done by the rhetoric of “worthy repentance” and “worthy communion.” One cannot but hear this language as speaking of a divine love that is conditional upon the human response: God will be merciful to us if we believe, if we repent, if we obey or at least try very hard. Despite all that Christ has done, the burden of salvation finally falls upon the sinner. The urgent question then becomes, How do we fulfill these conditions and how can we ever know we have fulfilled them? Jeremias offers sound counsel to the despairing, yet the despair is precisely the consequence of the exhortation to perfection that appears to call into question the all-embracing love of the Father: “those to whom the promise of the kingdom of heaven is proclaimed must fulfill all things perfectly and legitimately, and without them it shall be denied” (p. 39). For the Patriarch, justification before God is a purely future possibility; and the threat of everlasting damnation, even if rarely stated, is never far away.

It’s not just a matter of achieving in our teaching a scholastic kind of balance between divine grace and human effort but rather of understanding how authentic faith is grounded upon the unconditional promise of eternal salvation. Jeremias understands that the grace and mercy of God precedes and anticipates, yet he cannot declare the love of God as unconditional, for fear of cultivating sloth, indifference, and presumption. Not unexpectedly the Tübingen theologians found wanting Jeremias’s conditionalist construal of the gospel: “But it is necessary that the divine promise be most clear and certain, so that faith may depend upon it. For were the assurance and steadfastness of the promise shaken, then faith would collapse. And if faith is overturned, then our justification and salvation will vanish” (p. 126). To a large extent the parties are talking past each other. Why so? I tentatively propose the following: Patriarch Jeremias is reflecting on justification from within the existential struggles and dynamics of the ascetical life, in anticipation of the coming judgment; the Lutherans are reflecting on justification from within the existential situation of having heard the future judgment spoken to them in the preaching of the gospel.

Another oft-stipulated condition of salvation is the time limit. As we have seen, this is the central assertion of Fr Stephen De Young’s article “Hell (Unfortunately) Yes.” At some point, either at the moment of death or at the Final Judgment, repentance assertedly becomes an impossibility for the sinner: either God withdraws his offer of forgiveness or the sinner becomes frozen in his obduracy. With the former, the divine love is truly understood as conditional; with the latter, the divine love remains theoretically unconditional but now effectively impotent and helpless. As Dumitru Staniloae puts it, the reprobate are “hardened in a negative freedom that cannot possibly be overcome” (The Experience of God, VI:42). In both construals the gospel is necessarily presented as contingent promise: “If you repent before such-and-such a time, you will be saved.”

Those who confess the universalist hope, whether in its weaker version (St Gregory Nazianzen, Fr Hans Urs von Balthasar, Met Kallistos Ware) or its stronger version (St Gregory Nyssen, St Isaac the Syrian, Fr Sergius Bulgakov), object to—indeed emphatically protest against—the conditionalist portrayal of deity. Their objection is not grounded on the exegesis of a particular verse or two but rather upon a deep apprehension of the God they have encountered in Jesus Christ. How someone achieves this apprehension no doubt varies from person to person. Some experience it through their reading of Scripture, others through sacrament and liturgy, others through prayer and mystical experience, others through their service to the poor, others through philosophical reflection, still others through the love bestowed upon them by their neighbors and fellow believers—or any combination of the above. But once the love of God is known in the fullness and power of its unconditionality, there can be no turning back. From this point on, it becomes the prism through which all of reality is experienced. God is love—absolute, infinite, unconditional love—and it is this vision of God that now informs the faith, hopes, and dreams of the believer. As Balthasar declares:

Love alone is credible; nothing else can be believed, and nothing else ought to be believed. This is the achievement, the “work” of faith: to recognize the absolute prius, which nothing else can surpass; to believe that there is such a thing as love, absolute love, and that there is nothing higher or greater than it; to believe against all the evidence of experience (credere contra fidem” like “sperare contra spem“), against every “rational” concept of God, which thinks of him in terms of impassibility or, at best, totally pure goodness, but not in terms of this inconceivable and senseless act of love. (Love Alone is Credible, pp. 101-102)

In the lapidary words of the Apostle Paul: “Christ died for the ungodly” (Rom 5:6).

Yet there is much in Scripture that seems to argue against the unconditionality of divine love, including some of the parables and teachings of Jesus. We need not rehearse these texts. I imagine that we all have wrestled with them and continue to wrestle with them. I remember posing this question to Robert W. Jenson in the late 80s. His reply (rough paraphrase): “Go back and reread the Bible.” At the time I didn’t find the reply particularly helpful, but I eventually came to understand what I think he was saying—namely, “Try looking at the Bible differently. Put on a different pair of spectacles.”

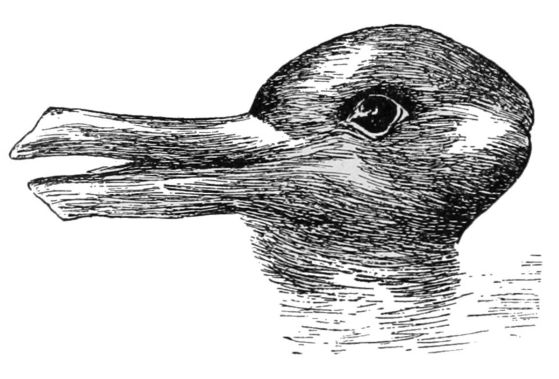

Is it a rabbit or a duck?

In his book Imagining God Garrett Green invites us to consider the role of theological paradigms in our interpretation of Scripture. Analogous to the role of paradigms within modern science, theological paradigms and metanarratives organize the data available to us and help us to make sense of it. “Our perception of parts,” he writes, “depends on our prior grasp of the whole” (p. 50). Perhaps the greatest stumbling block to a serious consideration of the universalist reading of Scripture is our inability, or refusal, to step outside the traditional paradigm of conditional love. How is it possible that God could accept us in our sinfulness, “just as we are”? What is needed is an imaginative leap to a new, but also very old, paradigm. Only then will we be able to apprehend the universalist reading as a coherent gestalt.

A few months ago a fellow Orthodox priest answered the question Dare We Hope “That All Men Be Saved?” thusly: “No, we do not dare to hope for such a thing. It is a delirious fantasy, neither a proper object of Christian hope, nor a proper subject for Christian speculation.” I was scandalized, just as I am scandalized by the anathemas recently delivered by my fellow priests at Orthodoxy and Heterodoxy. I understand why they believe that the universalist hope is heretical; yet when I read their articles, I am shocked nonetheless. I hear them proclaiming a different gospel than the one I have long, long believed and confessed. If God is not absolute, infinite, and unconditional love, then there is no good news of Jesus Christ and life is not worth living and dying. But if God is absolute, infinite, and unconditional love, then we may not restrict his desire, willingness, and power to accomplish his salvific ends for mankind; we may not put limits on his love, for he most certainly puts no limits on it. God wills our salvation and only wills our salvation.

For I am sure that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Rom 8:38-39)

What is at stake in this present debate? Nothing less than our understanding of who God has revealed himself to be in the crucified and risen Jesus Christ. Any qualification of the unconditionality of the divine love is intolerable. If there should come a point, any point, where God abandons the one lost sheep or no longer searches for the one lost coin, then God is not the Father of Jesus Christ, and our worst nightmares are true.

(Edit: though I originally intended to follow-up this piece with an article that explains why the dogmatic assertion of eternal damnation diminishes the eschatological proclamation of the gospel, my blogging heart ain’t in it at the moment. I need to get on with my summer. For an idea of how I might have proceeded, see “The Proclamatory Rule of the Gospel” and “Preaching the Kingdom.”)

Thank you, Fr. Aidan, with all of the gratitude that my heart is capable of expressing. I was recently in the Sistine Chapel and was devastated once again by such a despairing portrayal of God and our salvation through Jesus Christ, His Son. I wondered how anyone could be silent in the face of this portrayal. I was moved to tears by the ugliness of the message and the consequences, rather than the beauty of the art. I then encountered the same portrayal on orthodoxy and heterodoxy and it was equally heartbreaking. It was not just the content, but the way in which the content was expressed that was so disturbing. All I could hear from the writers was what I heard in the Sistine Chapel from the security guards – ‘Silence!’ ‘Silencio!’ – over and over again. Your words speak for many of us who are not as well immersed and versed, but who somehow know that the unconditional love of God is the only way, truth and life, and who have come into Orthodoxy with this hope.

LikeLike

Thank you for this. I will now have to read “Augsburg and Constantinople” when I have time. It sounds like a great read. Also, what is the name of the painting above? Thank you.

LikeLike

You’re very welcome, Dante. I believe that the painting is from a 14th century fresco at the Basilica of Santa Maria Novella: http://goo.gl/e1DZjR.

LikeLike

The correspondence between Patriarch Jeremias and the Lutherans is well worth reading. One has to be impressed with the Patriarch’s commentary.

LikeLike

The love of God, the basis of our faith, is rich beyond measure. I immediately thought of an old hymn written by George Mattheson in1882.

O love that whilst not let me go,

I rest my weary soul in thee;

I give thee back the life I owe,

That in thine ocean depths its flow

May richer, fuller be.

O light that foll’west all my way,

I yield my flick’ring torch to thee;

My heart restores its borrowed ray,

That in thy sunshine’s blaze its day

May brighter, fairer be.

O Joy that seekest me through pain,

I cannot close my heart to thee;

I trace the rainbow through the rain,

And feel the promise is not vain,

That morn shall tearless be.

O Cross that liftest up my head,

I dare not ask to fly from thee;

I lay in dust life’s glory dead,

And from the ground there blossoms red

Life that shall endless be.

LikeLike

I love this hymn, too, Norma.

Has anyone ever noticed that when we apprehend the love of God and the nature of the gospel truly and cannot contain the ecstasy this produces in the soul, the first thing we do (at least in reference to communicating this to others) is use poetry to express our hearts?

LikeLike

“The love of God is greater far, than tongue or pen can ever tell,

It goes beyond the highest star and reaches to the lowest hell.

O, Love of God, how rich and pure, how measureless and strong!

It shall forevermore endure, the saints’ and angels’ song!”

Bravo, Fr. Aidan. Bravo!

LikeLike

Father, I read the article you linked, and my first reaction to “wheat and chaff” is that it’s describing the purging of our passions. I suppose I could be wrong in seeing it that way, but I also see no reason to apply this to human decisions the way the author does. The immediately preceding verse says, “He will baptize you with the Holy Spirit and fire.”

I, too, have long struggled with understanding this “race against the clock” mentality. Why must there ever be an end to our ability to repent? What is so magical about death? If death eternally holds a human soul, then how exactly can we call Christ the conquerer of it? If He does not rest until he makes his last enemy his footstool, how could we ever say that some will spend their eternal lives chained in darkness?

LikeLike

RC, you might be interested on Solzhenitzyn’s quote on good and evil passing through every human heart. Fr. Stephen Freeman’s blog has the quote and reference–you could search it there.

LikeLike

Sergius Bulgakov: “Every person bears within himself the principle of gehennic burning.”

LikeLike

Fr Aidan: I’d like to highlight what I believe to be the two essential matters—the unconditionality of divine love and the eschatological triumph of the risen Christ.

Tom: Yes, and that the latter is grounded in the former.

Those who affirm irrevocable conscious torment have to envision the final triumph of God’s Kingdom in Christ as consistent with the final loss of (arguably) the majority of human beings existing in a continual state of sinful rejection and denial. I’m not sure what distinguishes ‘victory’ thus understood from ‘defeat’. This just looks like the defeat of God’s purposes and desires.

But you’re right. It all hangs on the relentless, unfailing and unconditional nature of God’s love. If God loves us irrevocably and unconditionally, and if God’s love constitutes the possibility of our Godward becoming, then the irrevocable foreclosure of created being is impossible.

LikeLike

I’ve recently come to the opinion that Jesus underwent baptism in order to perfectly repent that which we, in our sinful states, can only repent of imperfectly. By being in him, our repentance becomes perfected, also. Likewise with our faith.

Still…what of he who will not repent or believe, no matter how imperfect it might be?

LikeLike

Does such a person exist?

LikeLike

I hope not. Still, what if there is?

LikeLike

Repentance and belief are the conditions of salvation in our present state. They are not arbitrary; they reflect accurately what we, being what we are, need to arrive at in the process of assimilating God’s grace from a fallen condition.

But who knows whether, in the after-death state, some other, completely different conditions will be required for the full return to our Source and Father?

Things happen to us all the time which we didn’t choose and don’t want. I gather that it’s a First Principle that all creatures must return to the Creator in a manner consistent with their created purpose – whether they choose to or not. If it’s a question of whether some will continue to want something else when this has occurred, the possibility seems like a mere bugaboo. None of the situations that trick us into wanting wrongly will be available to us or left with us then. Pride will have no prop; delusions will be contradicted in the clearest terms. Only someone who genuinely and directly wanted his own utter destruction could continue, under those conditions, to withhold his inclination from God or refuse whatever God offered for his help.

If we insist on asking whether any human soul could be so ruined that he genuinely and directly desires his own utter destruction, I think that if such a thing were possible, that soul would not really be responsible any more… the eternal version of an insanity that needed to be cured, not punished. How can we envision a God who is unwilling and/or incapable of continuing to seek the cure of this poor inverted creature?

In The Incarnation of the Word, Athanasius represents God as being outraged by human sin – not in the sense that He is angry at human beings for sinning, but that he is angry at His enemy for ruining his good creation. Athanasius represents it as being utterly beneath God’s honor to fail in recovering his lost creation and returning us to his dominion. It was for this Christ came, he teaches. Although Athanasius does not proceed to teach universal salvation from this premise, I think that from this doctrinal standpoint things look a little differently on the present question.

If there really is a soul who won’t give in, even when all is said and done, will God be outraged at that soul or at the things that soul went through in life, by the hand of the devil, to ruin him so unimaginably? Whose side will he be on? On the side of the soul, or on the side of that which has ruined the soul?

You see, I think it’s a mistake to to eternalize evil or imagine it as standing out against God eternally. It’s almost like deifying it. Only God is eternal – surely that’s another First Principle.

LikeLike

Hi AR,

Thanks for a very thoughtful reply. I hope you are right. If Scripture were more unequivocal on these questions, perhaps I could agree with you completely. But I don’t think it is. I suspect it might have to be equivocal, in order to scare the hell out of some people – literally.

LikeLike

The gospel of fear is no gospel. If I told my wife that if she didn’t love me then i was gonna kill her do you think that she would now really ever be able to love me. now she might obey me but she would never be able to trust me. Always that fear in the back of her head. i hope i love him enough that he won’t kill me. God works the opposite of the way we think. Fear is not faith or trust. how could we trust in fear ? No it is love that conquers all according to divine love that we cannot comprehend. It is Love that wins.

It is love that will win over every heart. Is god Fair? No he is the one who pays the same wage to the worker that comes in the last hour. He is the one that even when the adulteress women should have been stoned by the law. What do we deserve ? nothing

what does God Deserve? Man made in his image. when he said it is very good.

All creation groans in expectation. Why? because when his righteous judgments are in the earth the people will learn righteousness . No one will say to his brother know the Lord for ALL peoples will know him.

LikeLike

AR, I think the very fact that it is God who created our human nature good and who in joining his divinity to our nature in Christ ensured its preservation through all attempts of evil to destroy that seed of good that persists in the most wicked of men is the “ace up God’s sleeve.”

Karen

LikeLiked by 1 person

Karen, that’s inspired! Well said and thank you.

LikeLike

Do you deny 2+2=4? If you understand the meanings of the terms, you know that the proposition “2+2=4” is true, correct? If you denied the truth of this proposition, then you are mad or confused or both perhaps. However, if you know what the terms mean, you will assent to the proposition’s truthfulness.

However, you will not feel coerced or compelled to assent to it except by the force of its self-evidence–“2+2=4” is obviously true. Yet the choice to assent to its truthfulness is not unfree is it? I don’t think so, but you could not help but assent to it if you understand the meanings of the terms.

Choosing God is much the same. If one doesn’t choose God, it is because of ignorance or madness or both. But if that person understands the terms, so to speak, then he or she cannot not choose God–God will be self-evident. It is not coercion so much as the removal of ignorance and madness (of course, this process may be, more or less, difficult depending on other factors like other choices one has made, so it could require a few Hells to remedy but remedied it will be).

LikeLike

“I hear them proclaiming a different gospel than the one I have long, long believed and confessed.”

And perhaps also a different gospel from the one Jeremias believed and confessed. Their implicit psychology seems not to fit his prospect of lifelong asceticism and repentance to open the heart to Love.

LikeLike

I presume that all of us in this debate fall far short of practicing the depth of asceticism that Patriarch Jeremias practiced.

LikeLike

I cannot presume anything about the ascetic practices of the several commentators. Whatever they may be, the rival narratives seem able to give them different lived meanings.

LikeLike

What were the ascetic practices of the thief on the cross who was enabled to recognize the Divinity of Christ and repent?

Karen

LikeLike

You wrote

// If God is not absolute, infinite, and unconditional love, then there is no good news of Jesus Christ and life is not worth living and dying. //

I mean, I have to ask: why don’t you just find a religion that you can be absolutely _sure_ has “love” as its absolute center, with an infinitely merciful deity who will never leave anyone behind?

LikeLike

George MacDonald somewhere (perhaps more than once) puts the matter in terms of St. John the Baptist’s question via his disciples as recounted in St, Luke 7:19.

LikeLike

SF, I’m afraid do not understand your question. If you are asking me if love is at the center of the Christian faith, then I can only answer, of course it is. Why would anyone waste their time with it otherwise?

LikeLike

What I mean is that if there’s legitimate academic debate as to whether all will eventually reconciled to God (as opposed to God’s mercy eventually “running out”) — and there certainly is — why not go for a religion where there _isn’t_ ambiguity here?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Are you asking why me why don’t I reject Jesus so I can go invent a religion of my own?

LikeLike

Nothing that drastic. Why not just totally excise the parts of Christianity you don’t like? (Literally throw them out of the canon.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

SF, have you considered the possibility that the unconditionality of divine love intrinsically belongs to the apostolic revelation? Have you also considered the possibility that the eternality of hell does not?

The Church is always involved in theological debate regarding the interpretation of Scripture and the authentic preaching of the gospel.

LikeLike

(This is in response to your most recent comment; didn’t see a place to reply to it there.)

You asked

// SF, have you considered the possibility that the unconditionality of divine love intrinsically belongs to the apostolic revelation? Have you also considered the possibility that the eternality of hell does not? //

I think that divine love was a very important part of the apostolic revelation. I certainly don’t think that it _exhausts_ it, or that everything can be at all harmonized with it.

I mean, if the early Christians indeed proclaimed the God of the ancient Israelites (and they certainly did), then this is the same god who once drowned every human on the planet (minus 8), and who gave laws to the Israelites demanding child sacrifice “in order that I might horrify them, so that they might know that I am the LORD” (Ezekiel 20:25-26); not to mention countless other horrors.

Leaving aside some of the highly decontextualized prooftexts often bandied about by universalists that purport to illustrate some meta-characteristic of God, I see no reason to assume that God’s eschatological temperament would be substantially different from his (apparent) earthly one. Especially since early Christianity emerged in a highly apocalyptically-charged environment where God’s eschatological mercy (toward the unrighteous) was largely absent: and many of the same traditions seem to be reflected in the NT as well as in many of the earliest (and later!) patristic sources.

LikeLike

I am not sure how “unconditional” is being used. Any ‘creatureliness’ is a ‘conditioned’ existence. The impenitence of a fallen volitional creature would seem to condition the fulfillment of God’s love of that creature and its perfecting.

Weighty, here, seems tgbelt’s saying, “If God loves us irrevocably and unconditionally, and if God’s love constitutes the possibility of our Godward becoming, then the irrevocable foreclosure of created being is impossible.” The question, surely, is, how has/does ‘God’s love constitute(d) the possibility of our Godward becoming’? Can any creatures be – and are any in fact – constituted indefinitely to resist their perfection by God’s love?

LikeLike

Father Aidan,

The passage from St. Basil cited by the Patriarch Jeremias does not, as far as I can tell, deny the unconditional nature of God’s love for mankind. What it does seem to deny is the notion of unconditional forgiveness. It seems to me that what is at stake in that debate is the reality of the forgiveness God offers to mankind. In the Catholic/Orthodox view, forgiveness involves a real purification of the sinner and not merely a forensic pronouncement on the part of God. It follows from this that, while God’s disposition towards us is always one of mercy and compassion, still this mercy and compassion must be met by man with a willingness to receive it, I.e., a willingness to allow God’s merciful love to draw us away from sin and towards Himself. It seems to me that neither Origen, nor St. Gregory, nor St. Isaac would deny this. They would simply add that God will eventually be able to obtain the requisite cooperation from each individual.

I have resolved the issue of universal salvation at the level of prayer. We must never forget that St Paul’s assertion that God wills the salvation of all is made in the context of prayer. We should pray for all because God wills their salvation. Why would God command us to pray for that which is impossible of achievement? Moreover, if we are assured that what we pray for is in accordance with God’s will (as is the salvation of all) then why can we not confidently hope for a positive answer to our prayer?

LikeLike

Ed, please define “forgiveness” in this context.

LikeLike

While we are thinking about what divine forgiveness means (and I actually think it’s more difficult a concept than it might first appear), let me throw out what first came to me about the unconditionality of love—refusing to take no for an answer. Whatcha think?

LikeLike

Which one is it: “we recognize that a loving person does not inflict his company on someone who hates it” or “[love is] refusing to take no for an answer”?

LikeLike

In this case, both.

LikeLike

Growing up in a church that preached both “unconditional love” and eternal conscious torment, I remember when it finally clicked for me that, in spite of all the pious language to the contrary, that God’s love was very very much conditional. And it made me mad. Not at God or the existence of hell (that was a whole different thing) but mad at the people who had presented an “unconditional love” to begin with. They had lied, or else they simply couldn’t recognize what a “condition” was. This was well before I knew that the idea of universal reconciliation even existed.

Robert Jenson, per this article, believes in “unconditional love” and yet is not a universalist. Why is that? I have to assume that it’s because love can be “experienced as wrath” eternally AND irrevocably. But can true divine “unconditional love” be eternally and irrevocably separated from the experience of it as such and still be called “unconditional love”?

I think anyone can understand that reality – love experienced as wrath. It’s based in love but it’s purpose isn’t EVER purely retributive – to somehow “satisfy” the one inflicting the punishment. But when such “loving chastisement” becomes irrevocable on the end of the one dishing it out (since there must not be a depth of human condition to which God is powerless against – where a person is just “too sick”) in what sense is it still unconditional love? Words seem to lose their meaning.

Same with the idea that love is unconditional but that a person rejects it. I get the reality of rejection of love. But when the concept of “irrevocable” rejection gets added in, that’s on God’s side. It implies a condition tied to the nature of how/when the irrevocable part kicks in. In what substantial sense does this love remain “unconditional”?

Bottom line, unconditional love most certainly is at stake. And the “irrevocable” side of things is where nearly all of the tension lies. It’s why I personally think that the conversation surrounding the biblical usage of “eternal” is so crucial.

I’d give up “unconditional love” all together – admit that it exists only in fairy tales – before I’d render the term meaningless by forcing a way for irrevocable eternal torment to be consistent with/a manifestation of unconditional love.

LikeLike

Mike, as you might have guessed, I agree with you. Ultimately I do not think one can reconcile the popularly held positions on eternal damnation with the unconditionality of divine love—one or another has to go.

Robert Jenson is an interesting case. He locates unconditionality within the communication-event of one person speaking the gospel (unconditional promise in the name of Jesus) to another. In this first- and second-person discourse, no conditions can be put on the fulfillment of the promise. Jesus is risen and he will fulfill his promises.

Does this mean, therefore, that all will be saved? At this point Jens would point out that the question indicates that we have moved from first- and second-person discourse to third-person theological speculation. It is within this abstract context that he believes that an affirmative answer cannot be given.

I still don’t know if I really understand his argument or if I have described it accurately.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan, what you describe Jenson as suggesting makes perfect sense to me spiritually, if not logically. Maybe this has an analog in Quantum physics–things behave differently when they are observed as opposed to not. A question must be answered differently depending upon whether we are merely asking from the purely speculative perspective or from a participatory perspective. In the latter case, the analogous sense in the spiritual realm means the perspective of faith as spiritual perception/vision–not speculation, which means standing outside of God’s Being).

LikeLike

Continuing in that vein, we will only be able to answer the question of ultimate salvation to the depth and degree we truly participate in God ourselves. I suggest those who have come to completely abide in Christ in this life, i.e., the Saints, “know” in this sense the answer to this question, but when someone comes to them asking the question from a purely speculative human perspective, the Saint’s answer will be “no, we cannot presume all will be saved,” and point out that from this speculative and human perspective what we can be sure of from the Tradition is the certainty of God’s love and desire to save all and the certainty of final judgement with true consequences in Eternity, including torment for those who have not loved God, and that the time for repentance is now.

LikeLike

Thanks Karen,

That makes a lot of sense.

Blessings.

LikeLike

Regarding Jenson on damnation, see pp. 360-365: https://goo.gl/roXJTC.

LikeLike

Maybe here’s a way of reconciling unconditional love and irrevocable torment: A person so despises God’s love that being in the presence of that love causes him torment. God cannot be other than love, and the person, though having the ability to repent, refuses to do so. He is forced to be continually in the presence of God, for there is no longer any other place to hide. Thus, he will be tormented eternally. It is irrevocable because the person continually chooses to refuse to repent.

But why not just mercifully annihilate this person? Perhaps the Incarnation, death, and Resurrection included all of humanity, so that all are now in Jesus, and cannot be separated from him. Thus all are immortal and cannot be annihilated.

But this is all just speculation on my part.

LikeLike

Mike H,

It sounds a bit from your description here like Jenson is accepting the modern belief that spiritual truth is to be found at the level of human logical analysis of the statements of Scripture–thus, hell’s never-ending torment is a foregone conclusion. It sounds like first person unconditional proclamation of the gospel is a practical accommodation to elicit faith in the hearer following the model of certain statements of Scripture, but not to be heard as an endorsement of universalism. This doesn’t sit well with me either. I believe the truth is more to be found at the level of paradox, and the real truth to which the Scripture is pointing cannot be known except by the spiritual discernment (the spiritual vision) that results from participation in Christ.

LikeLike

What you describe, Julian, is very similar to the position advanced by Kalomiros in his essay “The River of Fire.” Also see my article “Hell and the Torturous Vision of Christ.”

LikeLike

It sounds less retributive, but it just doesn’t make sense to me – not in anything other than a purely theoretical sense. If divine love irrevocably can’t be “experienced” as anything other than wrath, in what meaningful sense can it really be called “love” at all? Is the difference between divine love and divine wrath really only the perception of the object receiving it? 1 Cor 13 can be read that way? If the experience of love as wrath is irrevocable we might as well just call it something else.

LikeLike

I’m with you, Mike. Even at a human level, we recognize that a caring person does not inflict his company on someone who hates it. George MacDonald on the outer darkness makes so much more biblical sense to me: https://goo.gl/gzP4Ep.

But it makes all the difference in the world if the suffering inflicted has purgative, converting potentialities.

LikeLike

Fr. Aidan,

I don’t know enough about goo.gl to dare to go there from possible malware, etc., considerations. Do you have a reference whereby we could look up the MacDonald via (e.g.) Project Gutenberg?

LikeLike

David, the goo.gl is just the Google URL shortener. The longer link is: https://afkimel.wordpress.com/2015/01/29/the-consuming-fire/. The webpage is quite safe. 🙂

LikeLike

Father Aidan, let us take your definition of unconditional love as refusing to take no for an answer. Does this then mean that there are no conditions for receiving God’s forgiveness? Well, I think it depends upon what one means by the word “conditions.” All of the classical universalists believed that the wicked would have to undergo a severe purging of their sins before being granted entrance into the kingdom of heaven. Is this required purging a condition for entrance? It certainly would seem so, if we mean by the word “condition”, that upon which another thing depends. The idea that God, through His omnipotent power, will ensure that each individual freely meets those conditions does not make them any less conditions. Forgiveness of sins is, or so I think, intimately bound up with the purification of the sinner. If it were not; if forgiveness could be obtained without an actual interior cleansing from sin, then there would be no need for the sinner to be purified before entering the presence of God.

The passage from St. Basil the Great quoted in your article above does not contradict any of this. And it does not contradict the idea of unconditional love as the refusal to take no for an answer. In the passage quoted, St. Basil does not say a word concerning whether the “striving” that is required of human beings will or will not be eventually met by all. Indeed, Ilaria Ramelli seems to think that St. Basil held to apokatastasis. If that is true, and I believe that there are good reasons for thinking so, then the passage you quoted in your article would have to be understood in that light.

LikeLike

Ed, I still need a definition of forgiveness before I can opine on the conditions of forgiveness.

LikeLike

I’m not trying to trap you or anything. I simply do not know what “forgiveness” literally means after the death and resurrection of Jesus and the Pentecostal outpouring of the Spirit.

LikeLike

Fr. Aiden, from an Orthodox perspective, I have read in at least two places now,Wounded by Love and Nostalgia for Paradise, that repentance and forgiveness/remission of sins are the same thing, the same event. That says it all to me.

LikeLike

P.S. Nostalgia for Paradise is a compilation of talks (and/or writings?) given by Alexandre Kalomiros, put together and published by his son, John.

LikeLike

I’m not sure George MacDonald’s outer darkness would provide much relief:

“If the man resists the burning of God, the consuming fire of Love, a terrible doom awaits him, and its day will come. He shall be cast into the outer darkness who hates the fire of God. What sick dismay shall then seize upon him! For let a man think and care ever so little about God, he does not therefore exist without God. God is here with him, upholding, warming, delighting, teaching him–making life a good thing to him. God gives him himself, though he knows it not. But when God withdraws from a man as far as that can be without the man’s ceasing to be; when the man feels himself abandoned, hanging in a ceaseless vertigo of existence upon the verge of the gulf of his being, without support, without refuge, without aim, without end–for the soul has no weapons wherewith to destroy herself–with no inbreathing of joy, with nothing to make life good;–then will he listen in agony for the faintest sound of life from the closed door; then, if the moan of suffering humanity ever reaches the ear of the outcast of darkness, he will be ready to rush into the very heart of the Consuming Fire to know life once more, to change this terror of sick negation, of unspeakable death, for that region of painful hope. Imagination cannot mislead us into too much horror of being without God–that one living death. Is not this

to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thoughts

Imagine howling?

But with this divine difference: that the outer darkness is but the most dreadful form of the consuming fire–the fire without light–the darkness visible, the black flame. God hath withdrawn himself, but not lost his hold. His face is turned away, but his hand is laid upon him still. His heart has ceased to beat into the man’s heart, but he keeps him alive by his fire. And that fire will go searching and burning on in him, as in the highest saint who is not yet pure as he is pure.”

LikeLike

Julian, I think you missed MacDonald’s hope: precisely at the depth of the darkness, when the loneliness, despair, and isolationa are at their worst, the sinner becomes “ready to rush into the very heart of the Consuming Fire to know life once more, to change this terror of sick negation, of unspeakable death, for that region of painful hope.”

LikeLike

No, I didn’t miss it. The point is that the sinner who finds God’s love unbearable isn’t given a better option, but a worse one, though even the outer darkness is still a form of God’s love:

“But with this divine difference: that the outer darkness is but the most dreadful form of the consuming fire–the fire without light–the darkness visible, the black flame. God hath withdrawn himself, but not lost his hold. His face is turned away, but his hand is laid upon him still. His heart has ceased to beat into the man’s heart, but he keeps him alive by his fire. And that fire will go searching and burning on in him, as in the highest saint who is not yet pure as he is pure.”

I guess the question would be, could someone prefer the outer darkness to God’s presence?

LikeLike

In a word, no.

Fr Aidan’s point is that God is the destination of all knowing, choosing, and desire as such. God is the Good itself. In other words, there is no choice to be had between the Good itself and something else.

LikeLike

Okay, Karen, what is remission of sins?

LikeLike

🙂 Why, Fr. Aidan, as I believe you know well, remission of sins is when the penalty for sin is removed and sin is no longer imputed to the former sinner. It is when all symptoms of sin abate and cease. It is when the state of affairs becomes such that it is as if sin never existed in the first place. Thus:

repentance = forgiveness = remission of sins = justification

Are there any prizes for having the right answer? 🙂

LikeLike

Haha! You most certainly shall receive your prize.

The reason I keep pushing this is to more clearly specify why repentance must precede forgiveness/remission. Does our repentance in some sense change something in God—e.g., causes him to move from wrath to mercy. If that were the case, then I would advance a twofold response: (1) God’s love for humanity never changes. It’s not as if he literally gets angry with us but then cools off after we have offered our apology. (2) God has quite literally reconciled us to himself in the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. That is the ontological truth of who we are, whether we know it or not. We are already embraced and upheld by the love and mercy of the Father.

But the above is insufficient if we relate forgiveness to that which is in us that needs to be corrected, healed, redeemed, transformed that we might be made perfectly capable of enjoying the beatific vision. In that sense, we are never completely forgiven until we are made perfect. This doesn’t mean that we are not already accepted/justified—that has happened in Christ—but that “forgiveness” will always be needed until we are perfectly united to God through the Son in the Spirit.

For the baptized, therefore, repentance is not something that we do in order to get into Christ. It is simply what it means to live in Christ and with Christ. It is a relational mode of being and growth in the Spirit. True repentance is grounded upon God’s unconditional acceptance of us as sinners. It is this acceptance that allows us to acknowledge ourselves as sinners and to pray for God’s grace.

Anyway, that’s the outline of the argument I would want to elaborate.

LikeLike

Ultimately, I think that “conditions” in the context of this particular conversation have to do with whether there are “conditions” that can ultimately, irrevocably, eternally negate or supersede the love of God/God’s salvific purposes OR eliminate the possibility of experiencing “unconditional love” as anything other than torment.

It’s not so much “unconditional” in the sense of saying that a person doesn’t actually participate in their own existence or that actions have no meaning or consequence – the original post stated that “unconditional” doesn’t preclude repentance or “purging”. The “conditional” part relates to whether all things either find their ultimate place and meaning in the context and purposes of divine love, or whether there are some that irrevocably negate it.

LikeLike

Thanks for pushing me, Edward, to clarify what I mean by the unconditionality of the divine love. I’m still struggling to find a way to state what I want to say.

I came cross today this passage from philosopher Jerry Walls’s book Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory:

Okay, how does this sound? I’m not sure if it says what I want to say as a preacher (I want to say to a sinner “By the death and resurrection of Jesus, you are forgiven. Now repent and believe on him”); but I imagine that Origen and St Gregory Nyssen would be more comfortable with Walls’s interpretation.

For Walls, there are no conditions for God’s mercy, but we still need to turn to God, admit our wrong, and receive his forgiveness. Perhaps we might say that this is descriptively what it looks like for someone to enter into a forgiven state.

So what do you all think of Walls’s distinction between God’s unconditional offer of forgiveness and the reception of forgiveness?

LikeLike

We could, perhaps, say forgiveness in this sense is our personal appropriation of God’s forgiveness–one He has freely extended to all as a “gift and calling” that is “irrevocable.”

LikeLike

And that is probably what I would say, too. But we then need to recognize that we have really stretched the meaning of “forgiveness” at this point.

LikeLike

Yes, and I get that. But then that makes me want to ask why this is. Is it because we moderns have learned to read such language in the Scriptures with a flat literalism that doesn’t allow us to really hear the nuances that are plainly there when we read such things in their full context? What is true of the language of forgiveness and justification in the Scriptures is equally true of the language of salvation. we can both say, “I was saved in A.D. 33” and also “I am being saved here and now through conversion/faith and repentance.” Both understandings find ample support in the language of the Scriptures.

LikeLike

Re: Walls distinction, is it possible that one is just the tangible manifestation of the other? Perhaps the unconditional offer of forgiveness is itself a manifestation OF unconditional love? An even more fundamental question is “What is ‘unconditional love’ and what form does it take?”

The idea here is that forgiveness must be “freely accepted” – and that “repentance” is the form of this acceptance.

You said in an earlier comment that:

Repentance is not something that we do in order to get into Christ. It is simply what it means to live in Christ and with Christ. It is a relational mode of being and growth in the Spirit.”

In protestant circles, I’m used to hearing grace defined as “unmerited favor” without much talk of what form that favor might take…it’s “concrete” form comes across as a sort of legal fiction in the mind of God. Likewise, I think it’s important to talk about the form that “unconditional love” might take. Is it just a passive, formless disposition of divine goodwill existing in the mind of God, but that has no real, substantial, or tangible form? Isn’t it’s ultimate form manifested as communion with the object(s) of divine love? And if the offer of forgiveness is necessary to achieve that end, can divine love be “unconditional” if that offer is rekoved? If repentance itself is not merely a set of beliefs or behaviors that merits forgiveness (in a legal sense) but is instead “a relational mode of being and growth in the Spirit” in which unconditional love is realized/made manifest in the form of communion with God, then repentance itself is necessary because it’s a participation, it IS communion – it’s of a different category than “condition” in the sense that the word is typically used.

To me, there’s an essential connection between the formless idea of “unconditional love” and it’s manifestation – the possibility of it being experienced. If the offer of forgiveness and repentance is at some point irrevocably withdrawn (whatever form that might take) and the only remaining possibility is torture, in what sense can we constructively talk about divine love being unconditional? It becomes little more than an idea – the manifestation or realization of that love has been made impossible.

Ultimately we’re still talking about whether unconditional love (it’s concrete form being communion with God realized thru repentance) can be called “unconditional” if the possibility of the experience of it as such is irrevocably withdrawn. If it is/can be withdrawn, then I contend that “unconditional love” is a pious myth. It’s conditional.

LikeLike

I agree. The unconditional love of God must intend a concrete form in the human being, which is communion with the Trinity. Hence we cannot then speak of forgiveness in a legal sense, as one might forgive an offense or debt.

I also agree with the Lutherans who speak of faith as bestowed with the preached gospel, which is why I like to speak of the gospel in the mode of unconditional promise. If an unconditional promise is spoken to me, I only have two choices—to trust it or not. But I cannot trust if the unconditional promise is not spoken to me.

LikeLike

I don’t know–perhaps it’s more consonant with the Fathers, but I’m not sure how much sense it makes for forgiveness to be conditional on accepting that forgiveness. Could you say to someone “I forgive you, but only if you say thanks”? Could God? I am not sure. It seems like the offer of forgiveness *is* forgiveness. The forgiven can do with that what they want, but it doesn’t make them more or less forgiven.

What makes sense to me is that we are unconditionally forgiven and we may decide whether to *enjoy* that forgiveness or not. To the adulterous woman, Jesus doesn’t say “I’ll forgive you if you repent,” he says, “Neither do I condemn you; go and sin no more.” Forgiveness comes first. The Prodigal Son forms an intention to repent, but, when he approaches the Father, is forgiven before he can get any words out. Then, he may decide to enjoy the fatted calf, or reject it like his brother.

LikeLike

Yes, on the whole I agree with you, Nicholas. We are unconditionally forgiven, but it is up to us to decide whether we will *enjoy* it. To me it seems this whole line of inquiry in this thread has been underscoring the meaning of the Church’s teaching on synergy between the will of God and our will in the actualization of our salvation.

LikeLike

I don’t think that the enjoyment of something has comes from a conscious decision of the will to enjoy it. Whether a person can “enjoy” something would seem to be a matter of what that something ontologically is and our own real inner being. It goes deeper than conscious decision making (it seems to me, anyways).

But that being said, I’m still left wondering what form unconditional love takes towards the person that is supposedly unconditionally loved. Or does it exist without taking a form?

If the offer of forgiveness is a manifestation of unconditional love, and unconditional love can only be experienced as love when in communion with God through faith and repentance, then what if the offer of repentance is irrevocably withdrawn? Ultimately I think that “unconditional love” is meaningless if the conditions necessary to experience it as such are irrevocably withdrawn on God’s end. The option of eternally and perpetually choosing against God remains a theoretical option, but it seems that a person would have to concede that if freely choosing against God is still an option, so would choosing for God (whatever that looks like) no matter how hardened a person becomes.

So the conditions here take the form of a deadline for “acceptance”. Something like “God’s love is unconditional, but the ONLY means to experience it as such are very conditional and you’re on a countdown.” That’s what I’ve perceived as the Gospel asterisk in my own tradition. It sounds like a loophole or technicality. It might be “love”, but it certainly isn’t unconditional.

Or another way to ask the question – is there a deadline on when the older brother must join the party and eat the calf or else his “rejection” becomes irrevocable, at which point any tangible manifestation of unconditional love as love is permanently lost? If so, is that a condition?

LikeLike

Mike H.,

I agree. This has been the source of the angst that has driven a near 20-year constant hanging on God’s elbow (like Abraham in Genesis 18) to ask this question in ever more emboldened form, and to be honest this quest has been going on for me even longer than that. I have finally arrived at the place where I believe the invitation to repentance will never be withdrawn. If we believe it is, this can only mean, it seems to me, we have accepted a picture and understanding of the invisible God other than that revealed in Jesus Christ. What is the form that God’s unconditional love must take in Eternity? Nothing less than the form it has taken from before the foundation of the world–that as of a Lamb standing in the midst of God’s Throne as if it had been slain, that of the crucified and risen One!

LikeLike

Great questions, Mike.

I don’t think that the enjoyment of something has comes from a conscious decision of the will to enjoy it. Whether a person can “enjoy” something would seem to be a matter of what that something ontologically is and our own real inner being. It goes deeper than conscious decision making (it seems to me, anyways).

Well, here’s an example (that I am mostly stealing from Robert Capon). Being an introvert, I often don’t want to go to parties. Sometimes I get dragged into going. If I arrive and I still really don’t want to be there, I’m guaranteed to have a bad time, even if everyone else is having a great time. But if I let myself open up a bit, then I stop resisting the fun that’s being had, and I start having a good time too.

Now, is that a conscious decision of the will? I’m not sure. Maybe I have a drink or two. Or maybe a charismatic person is able to crack my shell. Or maybe I do decide, well, since I’m here, I might as well relax and enjoy myself. I’ve never quite been able to figure out what exactly is meant by the “will” in Christianity. The important movement toward God is often a letting go of or an opening to. Are those conscious decisions of the will? I don’t know.

But that being said, I’m still left wondering what form unconditional love takes towards the person that is supposedly unconditionally loved. Or does it exist without taking a form?

The person existing at all is a manifestation of unconditional love. After all, God goes on creating and sustaining us all the while we’re sinning and cursing Him. And not just creating us, but re-creating, holding out this offer of unconditional forgiveness, and allowing us to share in His love.

Or another way to ask the question – is there a deadline on when the older brother must join the party and eat the calf or else his “rejection” becomes irrevocable, at which point any tangible manifestation of unconditional love as love is permanently lost? If so, is that a condition?

Yes, that is a condition, and I don’t think there is some “deadline” for the older brother. At the point he does decide to join the party, he’s just as welcome to enjoy himself as anyone else. The first shall be last and the last shall be first and all that.

But more deeply, I’m not sure if temporal language is really the right way to talk about salvation. If eternity refers to the timelessness of God rather than an unending amount of human time, then the concept of the deadline doesn’t really make sense. In each moment, the entire work of creation, crucifixion, resurrection, and judgment is happening all at once.

LikeLike

Consider the story of Zacchaeus. What is its import? When I have preached on it, I have always emphasized that which Jesus said and did: “Zacchaeus, come down from there. We are going to have dinner together.” But I have heard at least one preacher emphasize the synergistic fact that it was Zacchaeus who freely decided to climb the tree. This, IMHO, completely misses the point.

LikeLike

Nicholas,

But more deeply, I’m not sure if temporal language is really the right way to talk about salvation.

I definitely hear you. Temporal language (along with language that speaks of God as just a bigger being) starts to break down if pushed too far. It’s really the only language that we have available though.

LikeLike

Considering the story of Zacchaeus, yes, Zacchaeus climbed the tree, but one could say he was drawn by Jesus’ being “lifted up” by virtue of His reputation spreading far and wide!

Grace is always there before, in and beyond all things. It is what empowers our human response.

LikeLike

On Zacchaeus, I agree that misses the point. He did go into the tree, but out of curiosity more than anything else: “to see who Jesus was.” But he is then clearly swept up in something outside of his control. The harder part, I think is the second part, where Zacchaeus attempts to justify himself before Jesus by his works. Jesus won’t have it, saying that He has “come to seek and to save that which was lost.” I read this as Jesus saying that it is not Zacchaeus’ measly good deeds (he is still rich) that save him, but only the grace of God.

Mike, I think there is some language available to us. There is just as much in Scripture to indicate a time-based interpretation as a timeless one. I think we need to have both.

LikeLike

SF wrote:

“I think that divine love was a very important part of the apostolic revelation. I certainly don’t think that it _exhausts_ it, or that everything can be at all harmonized with it.”

SF, I write as one who does not espouse an out and out universalism. I believe in the possibility of eternal damnation because, as far as I can tell, it is a dogma of the Church (I’m a Catholic, by the way). Nevertheless, the statement above is quite patently incorrect. In fact, Origen and St. Gregory of Nyssa and the other early supporters of apokatastasis did, in fact, achieve a harmony of all the judgment texts of scripture with the unconditional love of God. They certainly did not shy away from any of them. In fact, their exegesis of scripture is the only one which is able to affirm all of the judgment texts along with all of the universalistic texts without distorting their meaning.

LikeLike

I should clarify that if God really, truly is “all-loving,” then by definition anything he did would _have_ to be harmonized with it — even if he did something that seemed terrible and totally antithetical to this.

The problem is that for universalists, things like eternal torment and even annihilation _are_ thought to be terrible and antithetical to love, therefore any passages/traditions that on the surface seem to suggest these things can’t _really_ mean what they appear to mean.

It’s nothing more than exegesis being guided by theology; or at worst, it’s actually even (for example) _lexicography_ being guided by theology (which is the case any time you see universalists reinterpreting αἰώνιος: as those like Origen were wont to do). In that regard it’s no less than a type of “fundamentalism” itself.

They don’t really “affirm” judgment texts anywhere near to the standards of critical exegesis; they only affirm them as much as, say, Augustine would insist that “[Biblical texts/verses] which seem like wickedness to the unenlightened, whether just spoken or actually performed, whether attributed to God or to people whose holiness is commended to us, are entirely figurative.”

LikeLike

Why do you think face value interpretations are better interpretations? I certainly don’t think face value interpretations of, say, Genesis are better.

In fact, I think you would find it very difficult to get out of Scripture all the fundamental doctrines of Christianity with a literal hermeneutic like that.

LikeLike

I should add better than the classical allegorical hermeneutic.

LikeLike

Because allegoresis is almost always totally ad hoc, not to mention often explicitly apologetic. The broader context of the Augustine quote above is

// anything in the [Scriptures] that cannot be related either to good morals or to the true faith should be taken as figurative. . . . Jeremiah’s phrase “Behold today I have established you over nations and kingdoms, to uproot and destroy, to lay waste and scatter” is, without doubt, entirely figurative, //

The basic principle here is “if it makes our religion look bad, it’s obviously being misinterpreted.” This isn’t mature reasoning at all, but rather childish insistence that one _must_ be right.

This doesn’t mean that _some_ Biblical texts don’t demand a figurative reading. For example, in the Eden narrative, Adam and Eve were clearly never intended to be historical figures… though ironically enough, orthodoxy _demands_ that they must be. (WHich should show that religious people aren’t actually ever interested in truth, but only in finding ways to believe what they want to believe.)

LikeLike

But just because it is an allegorical interpretation does not mean it is not a true interpretation. There is no one exclusively true interpretation I don’t think anyway. As long as it testifies to Christ, is in harmony with the mind of the Church and the Spirit is guiding the reader, then one can come to a true interpretation but not necessarily the exclusively true interpretation.

And that is my point: the meaning of the Bible is not in the text itself waiting to be discovered like some answers to a crossword puzzle.

I think Gregory of Nyssa said that one must read Scripture in a philosophical fashion otherwise it will lead one into absurdities.

Origen, the father of patristic exegesis, said something along the lines of Scripture is about imparting spiritual truths, not historical truths, especially in the OT.

So I have no problem with what you say.

LikeLike

Exegesis must always be guided by theology. We already see this happening in the New Testament with St. Paul reinterpreting the OT in the light of Christ.

LikeLike

The fatal problem with that is that we can’t even begin to determine a theology _before_ exegesis in the first place!

Otherwise it’d be absurd: we could arbitrarily pick whatever ideology most appealed to us and then just (re)interpret everything to conform to it.

LikeLike

Father, I guess I would define divine forgiveness as the act by which God blots out man’s sin by giving him a share in His divine life. Mind you, I haven’t totally worked this out in my own understanding. But perhaps the more important question is, what does St. Basil mean by forgiveness?

LikeLike

On the contrary SF, the church and its theology of the Christ event came before the writing of scripture and scripture can only be understood as such , I.e. , as the unified word of God, within the church. Outside of the church, it is merely a collection of disparate and sometimes contradictory texts. But this is off the topic of this thread, so I will not pursue it further. I believe, however, that Father Aidan dealt with the topic of scriptural interpretation some time ago. Perhaps you could take a look at the archives.

LikeLike

Unfortunately we don’t really have a good idea about what Christian theology was like before the NT texts… other than some reasonable inferences we can make.

Again, we can’t magically decide that it was all about “love,” and then reinterpret everything in the texts in light of what we think lies inside or outside the bounds of love. Surely you can see how circular this is. “Early Christian theology was fundamentally about love, and therefore we can use the surviving tidbits of early Christian theology to prove that early Christian theology was fundamentally about love.” (Not to mention the other egregious exegetical leaps that are made once one is convinced of the position that one had already arrived at.)

LikeLike

When Julian speculates, “It is irrevocable because the person continually chooses to refuse to repent”, that would seem ‘unrevoked’ (in the sense of indefinitely protracted) rather than ‘irrevocable’.

Mike H (today at 6:30 pm) writes, “Ultimately, I think that ‘conditions’ in the context of this particular conversation have to do with whether there are ‘conditions’ that can ultimately, irrevocably, eternally negate or supersede the love of God/God’s salvific purposes OR eliminate the possibility of experiencing ‘unconditional love’ as anything other than torment.”

This sounds accurate, to me. I also take it to imply a distinction between “ultimately, irrevocably, eternally” and ‘indefinitely protractedly’.

This seems to me to involve ktisiology in the sense of volitional-creaturely ontology and teleology.

George MacDonald somewhere praises the first Q & A of the Westminster Shorter Catechism (while suggesting it/its authors might have done better to stop there than include some of its later matter): “Q. What is the chief end of man? A. Man’s chief end is to glorify God, and to enjoy him forever.”

Is this the telos of each and every created human person? And of each and every other created person? Does the ontology of either or both categories of created persons allow of (or, possibly, require) the possibility of the frustration of this telos either (1) “ultimately, irrevocably, eternally” or (2) ‘indefinitely protractedly’?

How does ‘time’ come into such volitional-creaturely teleological and ontological questions? Is ‘time’ (and/or some kind of ‘aevum’-analogue of time, where angels are concerned) a necessary ‘condition’ of possible ‘metanoial’ change? Or is possible ‘metanoial’ change a distinct, not-necessarily-temporality- (or temporality-analogous-) related teleological and ontological matter?

LikeLike

I agree with the unconditionality of Divine love. I believe that the revelation of Scripture is that this unconditional love will lead to the destruction and annihilation of one third of the spiritual beings so full of hate that they cannot embrace love and life. To destroy a creature who wills to remain in this evil condition is an act of love and mercy. Because human beings have always been subject to the evil influence of demons, it is reasonable to hope that all people freed of this influence will repent, be reconciled, and experience eternal life.

I believe that the early Church’s teaching on the Harrowing of Hades, and the dynamics of the particular judgment in the intermediate state, supports the belief in the salvation of most, if not all of humanity. If at the last judgment there are some human beings found to be in the same condition as that of the demons, then God’s love and mercy will end their existence. God’s victory does not have to be a shutout to be real and complete. Love wins because, sin, hatred, and death no longer exist in the New Creation.

LikeLike

Marc, I would love to know if any of the Fathers gave an allegorical interpretation of “one third”. I highly doubt, given the very symbolic nature of such passages, that its meaning is as literal as you assign it. Perhaps this is the amount of any of us which can ever be given over wholly to evil and merely represents the evil within us that is destroyed in our repentance and reunion with God. Wouldn’t that be a possibility?

LikeLike

Karen, The Book of Revelation is full of symbolic passages related to numbers. We know not to understand these passages literally. Seven and multiples of are symbolic of completeness, ten and multiples of are symbolic of fullness, and twelve and multiples of are symbolic of the Church. This is why the Church rejects the literal 1000 years of Chiliasm, understanding this as the fullness of time between our Lord’s Resurrection and Parousia. The two references in Revelation to 144,000 people are not literal but symbolic of the fulness of the Church in heaven and on the earth (12x12x10x10x10).

Regarding the term “one third,” it is probably also symbolic of a significant minority percentage rather than exactly 33.34%. In Revelation 8:7-12 the term “a third,” is used eleven times to describe the damaging effects of what might be a future nuclear war. Whatever the significant minority percentage of angels who rebelled with Satan and became demons is, the everlasting fire of Gehenna is prepared for them; not human beings (see Matthew 25:41).

Although I do not see how your thoughts about the percentage of possible evil in each of us relates to my post, I like the concept that human beings are on average more good than bad. However, there are some troubling exceptions known to us all. The question is whether the truly evil human beings are as intrenched in their hatred as the demons condemned to eternal death and annihilation in the eternal fire.

LikeLike

After following the discussion for a while, I couldn’t help but then want to return to George MacDonald and his “Unspoken Sermons”. There’s simply a treasure-trove of ideas concerning Universal Reconciliation imbedded within those scriptural elucidations. Getting the gist of what he is communicating through 19th century semantics and colloquialisms, can be a serious challenge. Nevertheless, looking carefully at his essay on “Justice”, MacDonald brings to a boil, several over-aching concepts that then crystalize into enigmatic truths, which help to unify and interconnect many of UR’s propositions.

Firstly, he sets the tone by suggesting that because God is inherently “Just”, and we, being his creative progeny, are then capable of knowing what true Justice is; it is imbedded deep within our character in an active and dynamic fashion. He then goes on to give his well-known “theft of his watch” analogy, where he adroitly reflects upon the relationship between the concepts of Mercy and Justice and how they are inextricably woven into Atonement and Reconciliation. These four form a reciprocal interlocking quartet of Love in action.

He states –

“How could it make up to me for the stealing of my watch that the man was punished? The wrong would be there all the same. I am not saying the man ought not to be punished—far from it; I am only saying that the punishment nowise makes up to the man wronged. Suppose the man, with the watch in his pocket, were to inflict the severest flagellation on himself: would that lessen my sense of injury? Would it set anything right? Would it anyway atone? Would it give him a right to the watch? Punishment may do good to the man who does the wrong, but that is a thing as different as important. Another thing plain is, that, even without the material rectification of the wrong where that is impossible, repentance removes the offence which no suffering could.”

He stands firm on the belief that ultimately, a “physical punishment” of the offense, in no way, would make up for the theft = the Sin of steeling and that only through repentance and reconciliation can “true justice” be served – Why? Because justice with God, is always coupled with His mercy. The two are conjoined twins of the same Spirit.

He goes on to say –

“Every attribute of God must be infinite as himself. He cannot be sometimes merciful, and not always merciful. He cannot be just, and not always just. Mercy belongs to him, and needs no contrivance of theologic chicanery to justify it.”

MacDonald believes scripture teaches that God is bound to destroy sin and it is in His character to do so in an obligatory fashion – and he did, and will continue to do so in those yet to be born into this creation.

He follows –

“Then indeed there will be an end put to sin by the destruction of the sin and the sinner together. But thus would no atonement be wrought—nothing be done to make up for the wrong God has allowed to come into being by creating man. There must be an atonement, a making-up, a bringing together—an atonement which, I say, cannot be made except by the man who has sinned. Punishment, I repeat, is not the thing required of God, but the absolute destruction of sin. What better is the world, what better is the sinner, what better is God, what better is the truth, that the sinner should suffer—continue suffering to all eternity?”

He continues –

“I am saying that justice is not, never can be, satisfied by suffering—nay, cannot have any satisfaction in or from suffering. Human resentment, human revenge, human hate may. Such justice as Dante’s keeps wickedness alive in its most terrible forms. The life of God goes forth to inform, or at least give a home to victorious evil. Is he not defeated every time that one of those lost souls defies him?”

There is so much more that he expounds upon concerning the topic and readers should determine for themselves the weight and value of his propositions in light of their relationship to the nature of God as revealed in scripture. From this reflective chunk alone, it is quite apparent though that he is not keen on the idea of perpetual torment in a “Hell” as an adequate recompense for unrepentant sins committed in this life, but rather the sinner himself will face a kind of post-mortem reconciliatory judgment if he does not look to Christ for the cleansing of his nature in this life.

LikeLike

Thanks Dave, that’s one of my favorite MacDonald sermons. I wonder if it is online anywhere? MacDonald believed that every human will is ultimately grounded in God’s goodness and can eventually be brought to repentance. I hope he is right.

LikeLike

It’s in the Third Series of Unspoken Sermons and at least two places it’s online are: transcribed at Project Gutenberg and scanned at Internet Archive.

LikeLike

Father, thank you, thank you, thank you for writing this.

This is the Good News that brought me to Christianity. This is the Good News that I heard preached in an Orthodox church and this is why I became Orthodox. This is the Good News that has been responsible for all of the spiritual blessings that have been bestowed upon me, and this is the Good News that I forget when my life goes off the rails.

You are absolutely right that once you see things through this lens, everything looks different. I have realized in reading these recent blog debates that I do read Scripture in a very different way from some other Orthodox. I read it through the prism of Christ’s death and resurrection, through which show forth His unconditional love of Man. All of the parables of judgment begin to take on a very different light in this context.