Jeff Cook has completed his three-part series on universalism: “Universalism and Freedom.” Given that Steven Nemes has already published a lengthy response over at his blog, I thought I’d restrict myself to one feature of Cook’s argument—the nature of divine foreknowledge. “If I were a Universalist,” Cook hypothesizes, “I would advance a principle”:

God has foreknowledge of the choices every free creature would make in any world he might actualize. This is a compatibilist line of thinking and it assumes that human freedom and God’s selection of a specific foreknown future are not incompatible, and therefore God may select a world with a story and final state he sees as best while honoring the choices of all human souls.

If I were a universalist, I would argue something like this: If we presuppose P, then God may look at the trillions of possible worlds he could actualize and see that in at least one of them all the free creatures eventually choose to embrace Him as Father and the community of God as their family through Christ. Let’s call the most desirable of these foreknown worlds “World F”.

If I were a Universalist, I would argue that prior to creating anything God has foreseen that if he were to actualize World F, all the potential sons and daughters in World F would eventually embrace their identity and the God who loves them. This view can make sense of two very important details: (1) It affirms human freedom, and (2) “God gets what God wants”: the redemption of all those he created.

Philosopher-types will immediately recognize this construal of divine foreknowledge as what is called Molinism: God knows all true counterfactuals of creaturely freedom, and he uses this “middle knowledge” in his creation of the world. It’s as if he runs in his mind zillions and zillions of simulations and from them chooses a specific simulation to actualize, namely, the world we now inhabit. William Lane Craig has popularized this understanding in evangelical philosophy.

Molinism neatly resolves the mystery of divine sovereignty and human freedom. It is easy to see why it might be attractive to proponents of the greater hope. But this is not a route that I can take. The image of God deliberating over scenarios of cosmic history and then picking the specific scenario that best realizes his creative intentions strikes me as anthropomorphic and incompatible with the transcendence of the Christian God. That we, as temporal creatures, should think of God as knowing future events before they happen is no doubt inevitable. Even many of the Church Fathers appear to have thought of divine foreknowledge along these lines (St John of Damascus comes immediately to mind), yet the naïveté of this view becomes apparent as we ponder more deeply on divine eternity and the creatio ex nihilo.

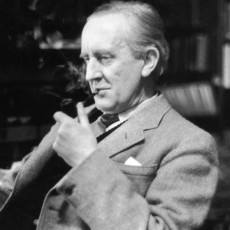

The Molinist assumes that God can know a history constituted by free agents, even though it does not exist. This idea may seem initially plausible. Did not J. R. R. Tolkien imagine an (almost) fully consistent secondary world of Valar, Elves, Men, Ents, Balrogs, and Orcs? Yet even still, these creatures and characters only became real when Tolkien brought the story to page, at which point they assumed lives and identities of their own. In a letter to W. H. Auden, Tolkien describes the process of creation as one of surprise: “But I met a lot of things on the way that astonished me. Tom Bombadil I knew already; but I had never been to Bree. Strider sitting in the corner at the inn was a shock, and I had no more idea who he was than had Frodo.”

The Molinist assumes that God can know a history constituted by free agents, even though it does not exist. This idea may seem initially plausible. Did not J. R. R. Tolkien imagine an (almost) fully consistent secondary world of Valar, Elves, Men, Ents, Balrogs, and Orcs? Yet even still, these creatures and characters only became real when Tolkien brought the story to page, at which point they assumed lives and identities of their own. In a letter to W. H. Auden, Tolkien describes the process of creation as one of surprise: “But I met a lot of things on the way that astonished me. Tom Bombadil I knew already; but I had never been to Bree. Strider sitting in the corner at the inn was a shock, and I had no more idea who he was than had Frodo.”

My analogy fails, of course—every analogy walks on three legs. The act of imagination is dependent upon the artist’s experience of a pre-existing world, and the story-teller may alter his narrative innumerable times. But the analogy points to the critical flaw in the the Molinist proposal. The assertion of middle knowledge demands, as David Burrell incisively argues, that God possess a knowledge “on the one hand of what might have taken place but does not, and on the other of what has not yet come to pass.” It therefore presupposes “determinations to the object known which only existence could bestow. … For if it is only esse [the act of existing] which grants an individual to be the individual it is, then God cannot know such an individual apart from granting it to be” (Knowing the Unknowable God, p. 104). God does not, and cannot, know Moses or the Virgin Mary or Al Kimel until he brings these beings into reality. The creatio ex nihilo thus implies, avers Burrell, a “metaphysics of actuality”:

Everything turns, of course, on the ability to characterize the creator of all things as the cause of being, and to understand the capacity to act on the part of self-determining creatures to be a participation in existence freely granted by that primary cause. If, on the other hand, we think of the creator as surveying universes of fully determinate possible beings “before deciding” which one to create, we are at a loss to understand how such “creatures,” possessed of at best “intelligible existence [esse intelligibile],” could be understood to be free actors and hence “fully determinate.” Hence the picture we have of God as creator will imply a specific metaphysics, and vice-versa. (Freedom and Creation in Three Traditions, p. 114)

A metaphysics of actuality, as opposed to a metaphysics of possibilism, requires that we reconceptualize the popular notion of divine foreknowledge. God does not know the future, for the future, by definition, does not exist. He knows, rather, that which he creates, or as Burrell puts it, “God knows what God does” (p. 108); and what he does is bestow existence. We may not be able to comprehend how this is so—the divine act of creation remains unfathomable to us—but we can see why it must be so.

God, who knows eternally and who knows by a practical knowing what God is doing, knows all and only what is, that is, what God brings into being. Yet by that knowledge, like an artist, God also knows what could be, although this knowing remains penumbral and general, since nonexistent “things” are explicitly not constituted as entities. By definition, an eternal God does not know contingent events before they happen; although God certainly knows all that may or might happen, God does not know what will happen. God knows all and only what is happening (and as a consequence, what has happened). That is, God does not already know what will happen, since what “will happen” has not yet happened and so does not yet exist. God knows what God is bringing about. Yet since our discourse is temporal, we must remind ourselves not to read such a statement as saying that God is now bringing about what will happen, even though what will have happened is the result of God’s action. (p. 105)

Given that we cannot picture God’s knowing of what-will-have-been, it is better to say that God does not now know what will-be and then correct the inevitable implications of that statement by insisting that God will not, however, be surprised by what in fact occurs, since what-will-have-been is part of God’s eternal intent, either directly or inversely, as in evil actions (ST 1.10.10). It remains that we will try, inescapably, to picture such an intent as God “peering into the future,” so we must then insist that the entire point of calling God’s knowledge of the “actual world” that of vision is to call to attention to the “contemporaneity” of an eternal creator with all that emanates from it, whereby what is, is so in its being present to its creator (ST 1.14.13). Yet the manner in which temporal realities are present to their eternal creative source is not available to us, so it is hardly surprising that we lack a model for God’s knowing eternally what-will-have-happened. For that reason I would prefer the arresting picture of God not knowing “the future” (which is also literally true) to the one which seems invariably to accompany the assertion that God does eternally know what will-have-happened—namely, that God can do what no one else can: peer into “the future.” God knows eternally what God brings about temporally; but this assertion does not entail that God now knows what God will bring about. The hiatus between eternity and time presents another manifestation of “the distinction” [i.e., the distinction between the transcendent Creator and the world he has made], so it is only plausible in the perspective of creation and never comprehensible.

What these grammatical remarks underscore is the relentlessly actual character of God’s presence to the world. The eternity thesis has the primary advantage of releasing us from so-called “counterfactuals of freedom,” which amount to asking what “Sally” would do in response to a particular invitation, were she to be created. (p. 110)

At this point we may suspect that Burrell is presenting a version of open theism, but the suspicion is unwarranted. He is, rather, advancing a Thomistic understanding of the eternal Creator who transcends created space and time altogether. God knows all things in his ineffable, eternal act of making and in this act is present to all beings and to all history.

Hence I must reject Jeff Cook’s hypothetical Molinist proposal. The universalist must find another way to reconcile divine sovereignty and human freedom.

(For more on David Burrell and divine foreknowledge, go to “Does God Know What Hasn’t Happened Yet?“)

Bill Craig. DBH’s favorite evangelical.

I hope 1,000 replies follow up on this post, because I’m all ears.

Tom

LikeLike

Thumbs up!!

LikeLike

I think passages such as Matthew 11:21 and Luke 10:13 pretty much ruled out Molinism for me.

LikeLike

John Milbank has drawn a strong distinction between the modern predilection for the possible and the pre-modern preference for the actual. I think middle knowledge thinks of God more as a supreme being than as the transcendent creative ground of Being. While moderns think of imagination as something that explores “possible worlds,” I think it much more likely that our imaginations mediate realities — angelic, demonic, sophianic. Imagination at its most inspired taps into an infinite actuality, rather than infinite possibility.

In any event, molinism presupposes a number of philosophical and theological choices that are in error.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Burrell would agree with you that Molinism and Tanner (and I imagine Hart also) would agree with you that Molinism, particularly as it is expounded by analytic philosophers, seems to think of God as a supreme being alongside all other beings.

LikeLike

Btw, Father, if you haven’t read Leaf by Niggle, it’s one of Tolkien’s really good short pieces . . .

LikeLike

Brian, is there any possible world in which I have not read Leaf by Niggle? 🙂

LikeLike

LOL. You’re the best.

LikeLike

“Fr Aidan Kimel has read Leaf by Niggle” is a necessary truth then. Nice.

LikeLike

The post addresses the question of foreknowledge and mentions open theism, so I thought this might be relevant:

“[T]o say that God knows in advance the works of freedom is a de facto annulment of freedom, its transformation into a subjective illusion…”

“If God created man in freedom, in his own image…then the reality of this creation includes his freedom as creative self-determination not only in relation to the world but also in relation to God. To admit the contrary would be to introduce a contradiction in God, who would then be considered as having posited only a fictitious, illusory freedom.” (Bride of the Lamb, p. 237)

“[T]o unite creaturely freedom with divine omniscience, one must say not that God foresaw and therefore predestined the fall of man, but that God, knowing his creation with all the possibilities contained therein, knows also the possibility of the fall, which, however, did not have to occur and can occur only by human freedom.” (p. 237)

“Although creation cannot be absolutely unexpected and new for God in the ontological sense, nevertheless in empirical (contingent) being, it represents a new manifestation for God himself, who is waiting to see whether man will open or not open the doors of his heart. God himself will know this only when it happens.” (p. 238)

“The synergism here is a mutual self-determination that has an element of novelty, actualized in different modes for the two sides in the interaction…Veiling his face, God remains ignorant of the actions of human freedom.” (p. 238)

LikeLike

Tom, what is the source of these quotations?

LikeLike

Yes, I admit. I left it out. 😛

It’s all Bulgakov.

LikeLike

Haha! I thought it might be Bulgakov. Can you provide us the titles and pages please. Thanks.

LikeLike

There are several passages in Bulgakov’s chapter “God and Creaturely Freedom” from The Bride of the Lamb (pp. 237f). It was Gavrilyuk (SJT 58[3] 2005; available online), Orthodox prof at the University of St Thomas here in the Twin Cities, who drew my attention to Bulgakov’s view. Gavrilyuk says:

“In addition, Bulgakov maintains that God also limits his knowledge of the future in order to enable genuinely free human choices… [He] knows all things in eternity and all future possibilities. For example, God foreknew the possibility of the fall, but God did not know that the fall was bound to happen, for this would entail that God caused the fall. God chooses not to know what exactly will come to pass in any temporal sequence ahead of time, because this would entail, Bulgakov believes, a strong doctrine of the divine causation of all things, which in turn would undo human freedom. To put it briefly, God chooses not to know future contingents in order not to determine the future and take away human freedom.”

Pretty interesting.

LikeLike

Okay, I did your homework and found the citations and included them in your comment.

LikeLike

Incidentally, possibilism is bad literary criticism. It has made a complete mess of the idea of fiction.

LikeLike

Expound, please!

LikeLike

AR, I fear my comment was rather poorly fashioned, and probably not all that relevant here. Nathless, if you’re asking for it, then… This’ll be a little off the cuff, as I’m somewhat wined and dined at the moment. But I’m glad I’ve I’ve piqued your interest. Apparently we’re both writers invested in questions of religious experience. I’d be happy to engage in a private correspondence on this subject; also, I’m trying to get a website up and running in a few days, which will address a nexus of literary and religious matters. What I’m saying is that hopefully we and other interested parties can discuss this kind of thing further, and more productively, in a more appropriate venue than Fr. Aidan’s blog, which I don’t wish to commandeer.

I think theological possibilism (to the extent I understand it, which may not be all that far) is analogous to an idea of fiction very widespread these days, whereby writers are conceived of as inventors, and their inventions comprised of or chosen from among possible and plausible worlds or scenarios or characters and details, etc. This, to me, is complete bunk. Possibility has nothing to do with writing fiction. Writing is not invention in the modern sense of the word; it is discovery. Writing is about reality, the actual truth beneath the surface of things; it is not a parade of fanciful notions that could, but never will, come to pass, thus amounting to nothing more than entertainment (at best) or verisimilitude, to use the ten dollar word. A work of art is not the actualization of potential, it is simply the true actuality of life that we normally can’t perceive. The imagination works on memory (Memoria mater musarum, as the ancients said — Memory is the mother of the muses), not on itself or on the airy nothing we call the future. A novel is not a series of choices made by the author (whereby the actual is sifted from the potential), or some sort of human creation from nothing (talk about impossibility!). It is true that the poet, as Philip Sidney said, ranges freely in the zodiac of his own wit. But the freedom of the artist is not a voluntaristic freedom, it is not a passionate affair of the will (whatever that is). Artistic freedom is, instead, the freedom to see reality behind appearance. It is a sight, or an insight, that is most certainly vouchsafed by the maker of that reality, but the gift elicits a terribly active and anxious response. To see in this way is only accomplished — so say great makers as diverse as Wordsworth and Proust — through the lens of memory. So for the artist, truth is subjective. It is also a-temporal, since it is the astounding conflation of past and present, an extraction of timeless essence from the seeming flow of existence out of potential (the so-called future) through the actual (the present) into the past (which is no longer possible: irredeemable, as Eliot calls it in the opening line of the Four Quartets). And as I said, the artist is the revelator of true life, the life that she has discovered, not the mere appearance that has been proposed, after analysis, by the one who proceeds solely according to the logical and empirical (i.e. whatever is necessarily apparent to all minds, the rational)…

There’s tons more to say, but I think that’s enough, if not too much, for here and now. Even this much probably sounds a bit silly. Like I said, I intend elsewhere to lay into this question of the reality of fiction much more rigorously. And I’d like to do it in such a way as to spark a discussion with others who share the vocation. One thing more, to be clear: I’m not saying I think possibility is an entirely faulty concept. The gist of my original comment was supposed to be that the possibilist’s God strikes me as similar, and therefore probably related on some deep cultural level, to an idea of the artist that is widespread today, and which I consider to be misleading in the extreme. A world where stories are just things people make up arbitrarily, for whatever reasons ulterior or overt, and governed, in their formal aspects, by whatever conscious or unconscious cultural inputs, is a world without even analogously accessible truth and reality, a closed world of impotent language that is indeed spoken by idiots, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing. Proust called analogy a miracle. One of the great critic George Steiner’s books, Real Presences, is a beautiful meditation on the kind of transcendent faith that is inherent in the act of using language, especially as verbal art. I am in their camp.

LikeLike

Jonathan, thanks! I’ve put Real Presences on my Amazon wish list.

Well I would love to discuss, expand and prod this thing elsewhere.

I hope it would not be too inappropriate to ask for a few clarifications here, though.

You said “Writing has nothing to do with possibility… writing is about reality.”

Do you mean that people should write about reality? Or that, somehow, they always do? Or do you mean that all writing becomes Real, or that good writing is somehow Real, a member of reality and not just a record of fantasy?

This commitment to memory as the mother of muse… does this imply a “tabula rasa” viewpoint where all our ideas are just recombinations of things we’ve experienced, and no archetypes are imprinted on our nature to be recognized? Or is memory, in the first instance, really that “recognition” of something we already knew in archetypal form, and which we are seeing instances of in the world around us?

Next, are you saying that the God of possiblism is slightly less than Creator because he surveys “possible worlds” and then chooses one to make, like people building their avatars in an online game? Are we concluding then that creation, whether artistic or “ex nihilo” only produces reality when the idea of it comes from within oneself?

Finally, may I point out that you are using “possible” and “potential” as synonymous? There are important reasons why we as Christians should preserve Aristotle’s distinction between these two important words. A human gamete represents a possible human being. But we have no duty toward merely possible human beings. However a human zygote has taken an important step and is now a potential human being. (It is “potent” it has the “power” to become a human being within itself.)

So it seems as if you might actually mean that fiction IS the actualization of the potential, even though you said the opposite.

LikeLike

Possibility and potentiality, however one wishes to distinguish them, are future-oriented, incomprehensible (or at least useless to us) without the idea of futurity. I don’t think art is.

I love this question: “Do you mean that people should write about reality? Or that, somehow, they always do? Or do you mean that all writing becomes Real, or that good writing is somehow Real, a member of reality and not just a record of fantasy?” — It reminds me of Gandalf at the beginning of The Hobbit when Bilbo Baggins says to him “good morning,” as yet woefully ignorant of the supernatural acumen of his interlocutor.

I meant that writing that is truly art is about — and is — the real. And I meant that one does not get to the real by just looking at things and people and events and then recombining them, though it is necessary to do this in order to make books (kind of like it is necessary to have bread and wine in order to have the eucharist). But books that are worth anything also do something else, they are inflected inwardly as well as exteriorly, just as holy communion is more than just the digestion of a very light repast. That inward inflection proceeds by way of memory.

What is memory? It is the inward presence (or re-present-ation) of what has passed. How can this be? I think about what is supposed to be happening in the mass/divine liturgy. “Do this in remembrance of me.” We have such a paltry idea of memory if we think this means something along the lines of “think about” or “recall to your consideration.” The work of art and the traditional Christian liturgy are a violation, a tearing the veil from the seeming thing, the mere appearance that time usually is for us. In either case, art or eucharist, we are dealing with subjective universality, i.e. access to, or a minute glimpse of reality rendered to every one present through the unique experience of an individual person (in the eucharistic context, a divine person).

I like a description of memory as the re-cognition of archetypal form which we have already seen but failed to know what it was we saw. As TSE wrote, the end of all our exploring will be to arrive where we started and know the place for the first time. We have to be reminded (or as one American patois can put it, “Remember me to do X”). The art work reminds. It does so, in part, by modeling what it is to remember in this deep, eternalizing way I am trying to invoke.

Sorry, this is not very helpful, but I gotta run!

LikeLike

addendum:

I’m not sure what you mean about an Aristotelian distinction between possibility and potentiality. I thought the word he uses is dynamis (in contrast to kinesis, energeia, entelecheia, aition and the rest of the gang I can’t remember), usually translated into Latin as potentia, a basic word for power. Potentia comes from potens, which is the present active participle of posse, the verb meaning to be able, and the root of our word possible. Devoid of qualification and context, potential and possible mean the same thing, conceptually. That doesn’t, of course, mean we use them in the same way. But that’s a separate issue.

Of course, back on the conceptual level, Aristotle distinguishes various kinds of dynamis. I suppose one could discuss a work of art with his terminology, but I’ve never seen it done well and I can’t really do it myself. What is the final cause of Ulysses or A Season in Hell? Could anyone care? Lord only knows. Honestly, Aristotle has never done much for me. I had to teach the Nichomachean Ethics once. Let me tell you, it was a disaster. Aristotle literally drove me to drink — I went to the pub directly after each class, where I would shoot pool and try not to think about “causation.” I’m more of a Plato kind of guy. Also — tellingly, perhaps — not very good at billiards.

LikeLike

THUMBS UP!

LikeLike

“Transcendent Ground of Being” – unoriginate source”- (agennetos)

Love your comment brian – it’s got me now digging into Tillich.

Cheers

LikeLike

Fr Aidan: Okay, I did your homework (re: Bulgakov) and found the citations and included them in your comment.

Tom: I thought the one reference I supplied would do it. Sorry.

I suspect the implications this has for our understanding of God’s knowledge of a temporal world (if I didn’t completely misunderstand Gavrilyuk when we discussed it) would—what’s the word?—“trouble” most Orthodox. But other than that, there’s no loss of providential presence in the world if God is understood (as Bulgakov seems to be saying) as knowing all possibilities grounded in himself and so as eternally responding to (to put it crudely) as opposed to saying God eternally knows the single story line creation will in fact take (by either determining it or…Help?…timelessly knowing it in its actuality). In Bulgakov’s view, one might say God overknows (as opposed to underknows) creation’s future by knowing all the vast possible trajectories the temporal world might/might not take and knowing as well that they all tend toward and end in him. But which particular possibilities will become the actual world? Bulgakov says that is not something God eternally knows. Gavrilyuk wasn’t comfortable (as I remember) with the implications this had for the temporal status of God’s knowledge of the temporal world. In other words—even if the open theists have a point relative to God’s epistemic openness regarding the temporal world, it may turn out to be a minor point inasmuch as God knows all possibilities for created being and as their ground knows as well that all possibilities begin and end in him.

LikeLike

I wish I knew Bulgakov’s work better. It would be great to bring him into conversation with Aquinas, Burrell, and Tanner. Bulgakov appears to believe that divine causality and creaturely causality are inherently competitive. Burrell & Company would strongly disagree.

LikeLike

Well, not competition as much as the simple distinction between a thing’s being ‘possible-but-not-actual’ and that thing’s being ‘actual’. The difference between the two isn’t a competition between the two. It’s just the ontology of a world of temporal becoming. It doesn’t introduce competition into ontology to say these distinctions are irreducible and to suppose God knows them as such.

I’m hoping to do lunch with Gavrilyuk before the end of the year and Bulgakov is all I wanna talk about.

LikeLike

I see, you’re asking about the causalities (divine and human) involved. Why should we think it problematic to see human choice (causation) as incompatible with being the effect of divine choice (causation)? Well, there are theological determinists who will agree there’s no problem. But I didn’t think the Orthodox posited that kind of relationship between God and the world.

LikeLike

Tom, you’re still thinking within the Calvinist/Arminian box, which is precisely what Burrell & Company invites us to move beyond.

LikeLike

I’m not sure I have much to add–I just wanted to register my own discomfort with the semantics of possible worlds. It seems an awfully strange way of talking about God. Are we to imagine that God, creating the universe through an immense outpouring of love, first sat down, pulled out pen and paper, and optimized across a variety of possible universes?

Personally, I much prefer the image of the reckless lover who granted us our freedom come what may.

LikeLike

It is a strange way of thinking about God and his act of creation. In fact, the more I reflect on the Molinist proposal, the stranger it gets for me. I’m sure that the “possible worlds” logic is helpful in thinking through various philosophical questions, but I suspect that it is ruled out when thinking about God. We cannot get behind the divine act of creation and know God in himself, apart from his creation. Or as Byzantine Orthodox like to put it, we cannot apprehend God in his essence, only in his operations (energeia). It may be that “possible worlds” logic invariably violates the divine transcendence. Not sure about this–just a thought.

LikeLike

That’s an interesting point. Maybe this is another way of putting it:

The Molinist schema described above has God choosing between a variety of possible worlds. Now, we might ask, where do these possible worlds come from? It cannot be that they precede God, because God is the source of all things. But if they don’t precede God, the God created them. So the question is: why is He choosing between them? Why didn’t He just create the world he wanted in the first place? Why does He need to create this list of options first and then choose the optimal world?

I think this reflects your concern that divine transcendence is violated. There is an implicit assumption that God is not the first thing.

LikeLike

I thought I’d bring into the conversation a passage from E. L. Mascall’s book He Who Is on divine foreknowledge. Like Burrell, he too notes the difficulty of our speaking about the divine foreknowledge because of the tensed nature of our language, but then draws a different conclusion:

LikeLike

I’d like to throw this out then I’ll be quiet for a while. Sorry for being so verbose. I’m very interested in the subject (possibility/actuality).

The interesting question for me is the ontology of possibilities. Do we conceive of our knowledge of possibilities as expressions of mere ignorance about the ‘one way’ things will eventuate? Or are possibilities the way things (with respect to much of the future) really are? If you view of creation is the latter, then the question of ‘the possible’ becomes even more interesting, for what’s it then mean to say God knows theses possibilities? Does he not know or relate to possibilities as possibilities because everything (about creation) is a fixed actuality to/in him? Are the formation of our sun, Caesar’s crossing the Rubicon, the Holocaust, Kennedy’s assassination—which we experience as temporal becoming—all known to God as a single reality equally ‘actual’ in all its temporal parts? In that case God knows no “possibilities-not-yet-actualized.”

This seems to be what Bulgakov was rejecting. It can’t be the case that creation in its temporal and free becoming is known to God as other than in the truth of its created being as temporal and free becoming. Knowledge of what is irreducibly temporal implies a temporal knowing. God knows the truth about the world, and the world’s integrity as created temporal becoming is reflected in the mode of God’s knowing it.

I know this is all hotly debated. It’s something I struggle with in thinking about the ontology of created possibilities. I agree such possibilities are grounded in the divine actuality; but that actuality grounds them as possibilities, not as actualities, which begs the question ‘What’s the difference between the two to God‘?

I will say this, though. Open theists:

(a) miss the sense in which all possibilities are enfolded within God’s creative decree, so there are no “surprises” and (as Bulgakov said) nothing “ontologically novel” that creation’s free becoming can add to God’s experience (since creation’s possibilities are precontained as logoi in Christ the Logos),

(b) miss the irresistible teleological disposition of all created capacities (that all things tend to the Good and end in God as their telos), and

(c) completely over-anthropomorphize God’s knowledge of creation’s possibilities by imagining God sitting down with pen and paper deliberating his way through his options, weighing the relative benefit of taking this route over that route, pacing the floor over the risks involved.

So as Nicholas says, perhaps creation is just love going for it. But not truly ‘reckless’ since all possibilities are simply (non-discursively) present to God and all possible routes end in God as their only final telos. There’s no risk involved if every true worth or value in created possibilities is finally realized in God. Creation is a risk-free venture—even if privated by sin en route. Romans 8, “the glory to be revealed in us will render all created suffering comparatively meaningless and irrelevant. I’m tempted to think of creation more along Hindu lines as “Lila” (‘divine play’).

Tom

LikeLike

Yes–reckless from our point of view, not God’s.

LikeLike

Nice post. I’m still coming out of my dogmatic slumber of analytic philosophy, so a lot of this is still difficult for me. Still, the Mascall bit seems to me much more helpful and precise than the Burrell. This is one area perhaps where I think the apophatic needs to be really stressed. Take this from Burrell: “By definition, an eternal God does not know contingent events before they happen; although God certainly knows all that may or might happen, God does not know what will happen. God knows all and only what is happening (and as a consequence, what has happened). That is, God does not already know what will happen, since what “will happen” has not yet happened and so does not yet exist. God knows what God is bringing about.”

An eternal God does not know contingent events *before* they happen, because there is no *before* (in our sense at least) for an eternal God (on at least one understanding of God’s eternity). But Burrell goes on to say something completely different: “God does not know what will happen…since what “will happen” has not yet happened and so does not yet exist.” The language here is difficult of course, but putting things this way seems to me to be a mistake – I cannot read this except as implying that God knows things in time in just the same way we do, and therefore cannot know what is in (our (and his?)) future. If the problem for free will is created by thinking that God knows *at the present or some past time* what will happen in our future, it’s enough just to stress that God’s knowledge doesn’t work that way (with perhaps the apophatic reminder that we can’t know how it works, and that we have it seems good systematic reasons for thinking it can’t work in such a way that it rules out freedom). I guess another way of putting this is that the metaphysics of actuality with the analogy of the artist who doesn’t yet know what he is going to create seems just as problematically anthropomorphic to me as the metaphysics of possibility.

LikeLike

Jeremiah, I couldn’t make heads or tails out of the same passage in Burrell.

Fr Aidan,

I get that the sense in which you’re wanting to express the non-competitive relationship between divine and human causation is not a species of Calvin’s (or Reformed) determinism. What I was pointing out is that Calvinists defend their view of (compatibilist) determinism in just the same terms you defend you non-competitive view—i.e., since God is transcendent cause and not just another of the same species of created causes, there’s no incompatibility (or competition) between the two (i.e., in attributing the effects of creaturely causation to divine causation).

You don’t want to affirm Calvin’s type of determinism. I see that. But you’re defending a different understanding of the relation in the same terms Calvinists invoke to defend their understanding of the relation. So my question is: What problem do you have with Calvin’s (compatibilist) determinism? Why do you reject it? It gets you transcendent divine causation of all created effects via the integrity of creaturely causation in a non-competitive way grounded in the nature of the former transcendently present in the latter? I get that you’re not a determinist. I’m just wondering why.

Tom

LikeLike

Tom, I’m going to throw your question back, given that you have recently read Burrell’ book. Why does he think there’s a critical difference between Aquinas and Calvinist?

LikeLike

I can’t make heads or tails of Burrell.

LikeLike

Haha, then you and I are in the same boat. But the important point for us is that Burrell and other folks like McCabe, Tanner, Hart, Turner, and Davies really do affirm free creaturely agency and reject any suggestion of Calvinist determinism.

LikeLike

But you do, do you not, attribute free creaturely choices to divine agency as equally as you attribute them to divine agency? If you don’t, then there’s no question that there’s no ‘competition’ involved. Competition only comes up as a complaint if mention has been made of creaturely choices being attributed to divine agency in such as way as to appear problematic (or in competition). So…what are you saying is the case between creaturely choice and divine agency that you think I’m mistakenly interpreting as ‘competitive’? If you’re not attributing creaturely free choices to divine transcendent causality, then it’s obvious there’s no competition. If you are attributing those choices to divine transcendent causality, how do you do so differently than Calvinists?

LikeLike

First sentence there; I meant to say “…as equally as you attribute them to ‘human’ agency.”

LikeLike

Bulgakov parses it out more helpfully (unless I’ve completely misunderstood him); i.e., all creaturely choices are eternally foreknown, enfolded in the creative decree, as possible ways the world might unfold. And of course every possibility once actualized irresistibly (even only tacitly) tends toward the Good and can only finally rest in the Good as its end.

Isn’t that all that needs to be the case about divine causality, i.e., the same God who grounds all possibilities sustains the world in its free choice of which possibilities are actualized? That’s different than saying God (in the mystery of his transcendent agency) actualizes as our world just those possibilities he decides are to be actualized through secondary (created) agency. You see the difference of course.

LikeLike

I’m not ready to embrace Bulgakov’s approach, as it seems to imply, as I said, a competitive, contrastive understanding of divine transcendence. When a theologian starts having to talk about God having to empty himself in order to make room for creaturely freedom, I get antsy. How is this not a violation of the grammar of transcendence, upon which so many Christian doctrines depend?

On this question every theological position involves trade-offs, as you well know. Perhaps it doesn’t ultimately matter. Does Thomist preaching on divine sovereignty and human freedom differ significantly from Bulgakovian preaching?

You may find of interest these passages from Aidan Nichols’s book on Bulgakov:

“In Thomistic language: Bulgakov accepts that God is the creature’s exemplary cause as also its final cause, but he will not hold with God’s being its ‘efficient’ cause. The reason is surely a misunderstanding of the due autonomy conferred on the creature’s existence by virtue of its very dependence on divine agency. The free action of creatures derives entirely from them, if also entirely from God, albeit in different modes” (Wisdom From Above, p. 70, n. 33)

“[Bulgakov] does not see that, in the condition of original sin, the drive of our freedom—of our will—towards God is blocked. It needs to be unblocked, to be liberated. At a deep level the will has itself to be freed before we can choose the divine good, the good that is God. When God intervenes to act on our will at its deepest source, he does not—as Bulgakov seems to think—despise our freedom by treating us as though we were machines or marionettes (two of Bulgakov’s favourite comparisons when outlining the Augustinian-Thomist theology of grace). On the contrary, he acts so as to release the spontaneity of our wills, to renew our freedom from within. And as our Creator, to whom we owe everything, including our capacity for free choice, this is no invasion of us. He is already, as Augustine wrote in the Confessions, ‘more intimate to me than I am to myself'” (p. 74).

LikeLike

Fr Aidan: I’m not ready to embrace Bulgakov’s approach.

Tom: Bulgakov and I are praying for you, him pulling from the front and I pushing from behind. 😛

LikeLike

Always nice to know that you and Fr Sergius are keeping me in your prayers. But wasn’t it just a few weeks ago you were bemoaning his kenoticism?! 😛

LikeLike

I knew that was coming!

Well, both us a bit. I was dismissing his kenoticism but am now enlisting his support in other ways. You were championing him in spite of his kenoticism and are now dismissing his view that God ‘makes room’ for creation as violating the very grammar of transcendence.

I can hear the sisters singing “How d’you solve a problem like Bulgakov?”

LikeLike

Jeremiah, thank you for your comment. I too found Burrell confusing. I think his intent is clearer when the quoted passages are read within the context of his wider argument, but it’s still not as clear as it should be, which is why I provided the Mascall citation. I think that Burrell and Mascall are saying the same thing, but I may be wrong. Both are pointing to the difficulty of speaking of the eternity of God because of our finitude and temporality. Tom Belt has also read Burrell’s, so he can correct me if I’m wrong.

The controversial sentence, I know, is where Burrell says that the future does not exist. He says this is literally true, because by definition the future is that which has not yet happened. Unlike Mascall, Burrell is willing to push this in order to make clear the inadequacy of our language when speaking of eternity. Herbert McCabe makes a similar point talking about the preexistence of Christ: https://goo.gl/Fl0z7j.

LikeLike

“The image of God deliberating over scenarios of cosmic history and then picking the specific scenario that best realizes his creative intentions strikes me as anthropomorphic and incompatible with the transcendence of the Christian God. ”

Anthropomorphic indeed. Leads to considering God The Father as some very old wise man in a beard managing creation from at a desk or divine laptop somewhere in heaven. Makes it difficult to separate inquiry into how or why God does or doesn’t do from how I might do it if I were God, and ultimately I don’t have a clue……

LikeLike

I’m not sure that McCabe’s position and Calvin’s are significantly different from one another when it comes to the most problematic aspect of such as non-competitive account–namely, the responsibility of God for evil. Granted, the only McCabe I have read is Faith Within Reason, but in the chapter “God and Evil” (and/or possibly “Freedom”–infuriatingly, I appear to have misplaced my copy of the book!) he justifies the presence of evil in a world without competitive creaturely free will by an appeal to evil’s ontological nothingness (which is certainly philosophically true, but I can’t help but share the dissatisfaction with it that David Bentley Hart expressed at the beginning of the lecture you posted–“we’re supposed to say that evil is nothing and then all the real suffering we see suddenly ceases to matter”)

. Vastly more problematic, though, is where in impeccable Calvinist fashion he makes God the ultimate reason for the damnation of those who reject him. I know that he embraces single predestination rather than double, but the distinction between the two– “killing” versus “letting die”–never seemed morally significant to me. Furthermore, when asked why God chooses not to save some, McCabe answers that He has no moral obligations to us–which is more or less the standard Calvinist answer (” What right does the clay have to question the potter?” et cetera). I am aware that many understandably see it as anthropomorphic to say that God has obligations to his creatures, but if you are uncomfortable with such language you can still say what Hart said: “would it make any sense to call a human being who acted in such a way ‘good’?”)

Unlike McCabe, as a universalist, you doesn’t have to face the awful eternal implications of such non-competitiveness, but the responsibility of God for temporal suffering still seems problematic. I would be fascinated to hear how Hart reconciles God’s absolute transcendence with His lack of involvement in temporal evils, asserted so strikingly in the Doors of the Sea.

Anyhow, sorry about the wall of text–and know that I find this discussion quite interesting and am grateful to you for awakening me from my naive Arminian slumbers!

LikeLike

Hi, Morgan. Thanks for mentioning McCabe. Given that McCabe emphatically rejects, with Aquinas, that God is responsible for sin and evil, I think that the line between him and Calvin is clearly drawn. But I agree with you that there is a problem here, which can only be solved by the universalist hope.

LikeLike

Thank you for the Nichols quote, Fr Aidan. You have my mind racing this week. I’ll assume that Nichols is reading Aquinas correctly. I don’t know. But as far as he describes Bulgakov’s own view, yes, that’s pretty much my view too.

Nichols objects to Bulgakov: “…but [Bulgakov] will not hold with God’s being [the creature’s] ‘efficient’ cause. The reason is surely a misunderstanding of the due autonomy conferred on the creature’s existence by virtue of its very dependence on divine agency. The free action of creatures derives entirely from them, if also entirely from God, albeit in different modes.”

Just to be clear, surely Bulgakov agrees that God is the efficient cause of our “existing.” We can’t have “due autonomy” in causing ourselves to “exist.”

It’s when one wants to say that the particular “exercise” of this due autonomy reduces transcendently in its determination to the will of God (that this exercise of will “derives entirely from us and entirely from God” and that the different “modes” make this non-problematic) that many have problems—not with transcendence per se; just which what one thinks it should incline us to believe about other things.

Just to be clear, I can say “God wills what creatures will” in the very qualified sense that God wills to sustain creatures in their sinful self-determinations. He’s holding them, even in their free choices, in existence. To the extent God’s gracious sustaining presence is necessary to all else, one might say God is even complicit in creaturely choice. But the divine and human agencies here (and I don’t take the former to be just a blown-up version of the latter) are not ‘willing’ the same thing. The creature wills some sinful end (mistakenly); God wills the creature’s abiding existence in his/her freedom to so will. Different ends are being willed. This isn’t problematic because the terminus or end of God’s sustaining will is the creature in its due autonomy willing (in this case) what God does not will. However, to say the terminus or end of God’s willing is the creature’s willing the act in question, that’s entirely different.

I may be misunderstanding Nichols, but it looks from your quote of him that he affirms this latter view that God wills what creatures will, i.e., wills that the creature wills as he/she wills, which isn’t Bulgakov’s view obviously. My point is—I don’t see that ‘transcendence’ should incline us to Thomas’ understanding of the God-world relation. Transcendence seems perfectly capable of supporting a view of that relation in which God efficiently wills our “existence” and not the “exercise” of our wills, especially if one adds that every possible exercise of created will irresistibly tends toward the Good (if only tacitly) and that no possible exercise of created will can remove one to an irretrievable distance. It’s transcendence which makes that distance impossible, not which reduces evil choices to divine causation.

Tom

LikeLike

Tom, I don’t want to keep going back and forth on this. My challenge to you is this: to so understand the position of Aquinas & Co. that you could cogently present and defend it in a debate. When you can do this, then you will understand why David Hart finds libertarianism silly. And in case you are wondering: I’m not at that point yet either. But there is something important here, a metaphysical intuition or apprehension, that niggles at me and won’t let go. And I suspect it’s niggling at you, too. 😉

LikeLike

Jeff Cook has such a wonderful spirit that it pains me to point out that his discussion is filled with technical errors and flaws.

As an illustration, consider the following statement: “That is, it could be the case that in every possible world where you and I exist, we do not embrace God or his community.” But if that were true—if there were no possible world in which you and I “embrace God or his community”—then it would be logically impossible that we should do so; and if this should be logically impossible, then we would have no libertarian free will in this matter at all. I am truly free with respect to doing A in a set of circumstances C, after all, only if there is a genuinely possible world in which I do A in C and also one in which I refrain from A in C. Accordingly, we can freely reject God and his community only if there is a possible world in which we freely embrace both of them. Cook’s discussion thus undermines the very possibility of libertarian free will in the matter of salvation.

What Cook evidently wants to describe is an imagined condition similar to what Bill Craig has called transworld damnation (and I have called transworld reprobation); Cook himself calls it transworld irredeemability. But he has clearly misunderstood Craig’s argument. For Craig would never claim, as Cook does, that “there may not be a possible world in which all of God’s creatures freely choose to be redeemed”; to the contrary, Craig would acknowledge the existence of infinitely many such worlds. But all of these genuinely possible worlds, Craig insists, could, for all we know, belong to the set of worlds that lie outside of God’s power to make actual. Neither would Craig ever say, as Cook does, that “God could actualize any world that is possible” For if libertarian freedom is even possible (whether or not it actually exists), then again there are infinitely many genuinely possible worlds that lie outside of God’s power to make actual. So once again, Cook makes a claim that undermines the very possibility of libertarian free will.

If anyone wants to get clear on the basic concepts here, the classic starting place would be Alvin Plantinga’s discussion, published some 40 years ago, of “Leibniz’s Lapse” in God, Freedom, and Evil, pp. 34-44. It is important to stress that Plantinga persuaded almost everyone in the philosophical world, both theists and atheists alike, that at least some genuinely possible worlds are such that not even an omnipotent being would be able to actualize them. I try to provide a less technical explanation for non-specialists in The Inescapable Love of God, pp. 160-161.

-Tom

LikeLike

Tom – Thank you for responding.

You wrote, “As an illustration, consider the following statement: “That is, it could be the case that in every possible world where you and I exist, we do not embrace God or his community.” But if that were true—if there were no possible world in which you and I “embrace God or his community”—then it would be logically impossible that we should do so; and if this should be logically impossible, then we would have no libertarian free will in this matter at all …Cook’s discussion thus undermines the very possibility of libertarian free will in the matter of salvation.”

So, I am arguing in the post that if I were a universalist, I would argue from a specific form of Compatiblism. You may as a universalist argue for libertarian freedom, but I think this raises new questions. As I wrote in the post, those who affirm libertarian freedom cannot be confident that all will freely and eventually accept the grace of God. One could only be hopeful. Worse still, if a soul continues on after death and they freely choose against God’s grace they would be stuck in something like the traditional hell–which I assume most universalists find repugnant.

You wrote, “What Cook evidently wants to describe is an imagined condition similar to what Bill Craig has called transworld damnation (and I have called transworld reprobation); Cook himself calls it transworld irredeemability. But he has clearly misunderstood Craig’s argument.”

I’m not invoking WL Craig’s work. And “transworld irredeemabiility” strikes me as coherent and a **possibility** for at least one hypothetical personality.

You wrote, “Neither would Craig ever say, as Cook does, that “God could actualize any world that is possible” For if libertarian freedom is even possible (whether or not it actually exists), then again there are infinitely many genuinely possible worlds that lie outside of God’s power to make actual. So once again, Cook makes a claim that undermines the very possibility of libertarian free will.”

I agree, but again, my post focuses on compatiblism.

You wrote, “Plantinga persuaded almost everyone in the philosophical world, both theists and atheists alike, that at least some genuinely possible worlds are such that not even an omnipotent being would be able to actualize them.”

This would affirm my point and not yours, yes?

Thank you for your courage and work Tom!

Grace and peace,

Jeff

LikeLike

Jeff,

TomB here. Forgive me for inserting a response to something you addressed to TomT.

You wrote: “As I wrote in the post, those who affirm libertarian freedom cannot be confident that all will freely and eventually accept the grace of God. One could only be hopeful. Worse still, if a soul continues on after death and they freely choose against God’s grace they would be stuck in something like the traditional hell.”

A libertarian could argue that though we are free to renew our rejection of God, we are not free to irrevocably reject God, that is, we cannot absolutely foreclose upon ourselves all possibility of Godward movement. This doesn’t get you a terminus ad quem, some ‘line in the sand’ or point at which God says, “Enough already. I’m saving you right now.” Some universalists may want that. However, it doesn’t follow from denying annihilationism and ‘irrevocable’ conscious torment that ‘line in the sand’ universalism is the only option left us.

One can suppose the will must be ‘converted’, won to faith, within and through the constraints of finite reason and volition. We must come to freely give ourselves to God, in which case there’s no presently guaranteeing a fixed point at which God just decides to “make” that happen. But though we are capable of renewing our rejection of God. We are not free to determine for God that he does not love us, that such love does not pursue us, or that that such loving pursuit of is not in fact the very ground of every possibility of turning toward him. God determines created existence as an irrevocable openness to him. We can misrelate to that and contradict it, living in the fantasy of having rid ourselves of it, but we cannot abolish it absolutely. To ‘be’ is to be ‘invited’ Godward. And where the will yields, on whatever small level to which we may have private ourselves but remain incapable of irradicating, it grows ever freer. “Eventually” all are won—not in a guaranteed, terminus ad quem, line in the sand, compatibilistically get what you want sort of way, but in a God’s got all the time in the world and loves us unconditionally and we’re not going anywhere sort of way.

There are good metaphysical reasons (too boring to go into here) for believing that created sentient being cannot absolutely foreclose upon itself all possibility of moving favorably toward God (as the immediate source and ground of its being). That possibility just is the ground of our being as graciously given. We’re asymmetrically related to it. It’s our logos. We’re no more free to annihilate (or irrevocably foreclose upon it) than we are to constitute it.

TomB

LikeLike

*eradicating. How erashunal of me.

LikeLike

Does this answer work if salvation entails something like taking up one’s own cross and dying to one’s self?

Good thoughts!

LikeLike

Jeff: Does this answer work if salvation entails something like taking up one’s own cross and dying to one’s self?

Tom: As I see it, there’s no salvation apart from self-denial—either side of the grave.

LikeLike

Thanks for your response, Jeff. Perhaps I misunderstood your intent in your discussion of universalism. For even though I noticed your use of the term “compatibilism,” which I did not fully understand in the context, I thought, even as Father Kimel did in his original post, that you were arguing from an essentially Molinist point of view. I thought you were in effect saying that, if you were a universalist, you would defend it from a Molinist point of view. You thus suggested that “God may look at the trillions of possible worlds he could actualize and see that in at least one of them all the free creatures eventually choose to embrace Him as Father and the community of God as their family through Christ.” That looked to me like a typical Molinist attempt to reconcile God’s providential control with a libertarian understanding of human freedom.

But perhaps I was wrong about this, as I said. Even so, however, the same problem remains. For there is simply no reason, so far as I can tell, why anyone, whether a compatibilist or a libertarian, should accept your claim that “there may not be a possible world in which all of God’s creatures freely choose to be redeemed.” A compatibilist will argue that, given a compatibilist account of free will, God could simply cause it to be the case that all sinners “freely choose to be redeemed”; and a libertarian will argue that, given the standard libertarian account of free will, all sinners are free with respect to their redemption only if there is indeed a possible world in which they all “freely choose to be redeemed.” So in either case, there surely is a possible world in which “all of God’s [sinful] creatures freely choose to be redeemed.”

Does that make any sense to you? If not, could you perhaps explain further why you think there may be no possible world in which all “all of God’s [sinful] creatures freely choose to be redeemed”?

-Tom

LikeLike

Excellent. Thank you for clarifying the positions.

You wrote, “For there is simply no reason, so far as I can tell, why anyone, whether a compatibilist or a libertarian, should accept your claim that ‘there may not be a possible world in which all of God’s creatures freely choose to be redeemed.'”

It seems to me, the burden here is not on me but on you to prove that such world’s are impossible. If they are possible then the claim God has the power to save all and the will to save all still does not necessitate universal salvation.

You wrote, “A compatibilist will argue that, given a compatibilist account of free will, God could simply cause it to be the case that all sinners ‘freely choose to be redeemed.'”

So, I think this could be either metaphysically impossible, or it oversteps. Making someone freely choose doesn’t seem very free; a portrait of God honoring his children’s decisions and what is required from a human soul to become a child of God and reflect God’s image will be important here.

You wrote, “a libertarian will argue that, given the standard libertarian account of free will, all sinners are free with respect to their redemption only if there is indeed a possible world in which they all ‘freely choose to be redeemed.’ So in either case, there surely is a possible world in which ‘all of God’s [sinful] creatures freely choose to be redeemed.'”

I don’t see how the conclusion follows here. Can you help me out.

You asked, “Could you perhaps explain further why you think there may be no possible world in which all ‘all of God’s [sinful] creatures freely choose to be redeemed’?”

I’m saying this is a metaphysical possibility that’s not known to be false. And if it is a possibility, the strong claim that God has both the power and will to achieve universal salvation and therefore must be able to achieve universal salvation fails.

I make a series of other arguments in the original post detailing why, even if such a world were possible, God may select other worlds. I’d love your thoughts. It is here: http://www.patheos.com/blogs/jesuscreed/2015/07/20/universalism-and-freedom-by-jeff-cook/

LikeLike

I’m sorry, Jeff, but I fear that I am not now following our discussion at all. So I am now wondering whether you and I may be using the term “possible world” in two very different senses and, in particular, whether you may be using this term in a rather non-standard way, namely, in the same way that some Molinists have used the term “feasible world.” I propose, therefore, that we slow down a bit and take this one tiny baby step at a time.

To begin with, then, could you perhaps clarify for me your own use of the term “possible world?” Just what is a possible world, as you understand it? I ask this for two reasons: first, because I still have no clear idea why you think that “there may not be a possible world in which all of God’s creatures freely choose to be redeemed,” and second, because your claim that “this [i.e., the absence of any such possible world] is a metaphysical possibility” strikes me as simply incoherent. It is like saying that some logical impossibility, such as two plus two equaling five, is in fact metaphysically possible. But if what you really want to claim is the metaphysical possibility that certain genuinely possible worlds may not be feasible for God—that is, may not lie within God’s power to actualize—then that is a view I can certainly understand and even accept. That view, however, also entails that there are indeed possible worlds “in which all of God’s creatures freely choose to be redeemed.”

As I understand a possible world, by the way, it should suffice for our purposes to think of it (roughly and not quite accurately) as a complete description of the way things could have been. Anyway, I also want to thank you for your own generous spirit and for your willingness to put up with me.

-Tom

LikeLike

Tom, excuse the silly question, but I do not understand how a world might be metaphysically possible but unfeasible for God to realize. Could you explain that for us. Thanks.

LikeLike

Tom, thanks for continuing this discussion.

By “Possible Worlds” I am saying “a state of affairs God could have actualized.” And if God has foreknowledge of all states of affairs then God can see all potential outcomes of any state of affairs God may make.

I would argue there are not an infinite number of possible world’s and there are not an infinite amount of distinct, potentially free beings.

My initial argument would then suggest that it may be a metaphysical fact about all potential free beings and the countless possible worlds they inhabit that in all possible worlds it may be the case that not all freely embrace God’s grace.

I suppose, for arguments sake, I think it very likely that there is one possible in world in which just 5 free people are created and they all come to faith, but in this case I think God would be giving up other goods which God desires.

You wrote, “As I understand a possible world, by the way, it should suffice for our purposes to think of it (roughly and not quite accurately) as a complete description of the way things could have been.”

That works for me. It may be the case that there are no “ways things could have been” in which all embrace God’s grace. That could be a metaphysical truth.

Much love to you!

LikeLike

I have made a couple of minor changes to the text to make it clear that Dr Cook is not necessarily advocating Molinism per se. It’s really no more than a thought experiment for him.

And I hope I have made it clear in my own article why I presently do not embrace Molinism—it seems to imply an understanding of divine transcendence that is less than divine transcendence. Another way to put: The God who creates the world ex nihilo transcends compatibilism and libertarianism.

LikeLike

Thanks man!

LikeLike

I am thrilled that Drs Talbott and Cook are presently discussing here on EO this most interesting subject of divine foreknowledge. For those who are interested in this subject, you may find of interest Tom Talbott’s article “Providence, Freedom, and Human Destiny” of real interest.

LikeLike

Father Kimel wrote: “Tom, excuse the silly question, but I do not understand how a world might be metaphysically possible but unfeasible for God to realize. Could you explain that for us.”

There is nothing silly about your question, Father, and the answer to it takes us to the very heart of Alvin Plantinga’s Free Will Defense. The basic idea here is that actualizing a world as a whole, or at least actualizing one that includes created free agents, is a joint project between God and these created free agents. Here are a couple of paragraphs from The Inescapable Love of God (pp.160-161) in which I try my best to explain this idea, which may seem utterly unintuitive to some, for a general audience.

“One difficulty, then, for any anti-theistic argument from evil is that of knowing which states of affairs are, and which are not, genuinely possible. A second, more serious, difficulty is also more difficult to grasp. If it is not within God’s power to do the logically impossible, then neither is it within his power to make actual every possible state of affairs that he might like to make actual. Many philosophers, following Leibniz, have assumed that an omnipotent being could create (or make actual) any possible world he pleased, where a possible world is (very roughly) a complete description of the way things might have been. As Alvin Plantinga demonstrated several decades ago, however, Leibniz’s assumption is clearly false. If there are logical limits to what an omnipotent being can do, then many possible states of affairs, no less than impossible ones, lie outside the bounds of his direct causal control.

“The reason for this is perhaps easiest to grasp in connection with the libertarian conception of human freedom. I do something freely in this libertarian sense, remember, only if it is within my (unexercised) power, at the time of acting and in the very same circumstances, to refrain from doing it; and I refrain from doing something freely only if it is within my (unexercised) power to do it. It is within my power to refrain from something I do, moreover, only if, first, it is logically possible that I should refrain from doing it, and second, nothing outside my control should causally determine (or necessitate) my doing it. Accordingly, if my act of writing this page is free in the relevant sense, then it must have been possible for me not to write it; and if it was possible for me not to write it, then there is a possible world in which I do not write it. That world—call it W—might be the same as the actual world (at least in certain relevant respects) up to the time of my writing, but in that world I choose to spend my time in another way. But though W is truly a possible world (a way things might have been), it is a world that God was powerless to create; had he tried to make it actual, he would have failed. He could, of course, have caused me to refrain from writing, but then I would not have refrained freely [in the relevant libertarian sense]. In the exact circumstances that obtained, only I could bring it about that I freely refrain from writing. Since I could have chosen not to write, W is indeed a possible world; but since I did not make that choice and God was powerless to bring it about that I did so freely, he was also powerless to create W [hence, W was in fact unfeasible for God]. If free will (of the libertarian kind just described) is even possible, therefore, there may be infinitely many possible worlds that God, however omnipotent he may be, no more has the power to create than he has the power to produce a sufficient cause for an uncaused event.”

How successful this explanation may be is for others to judge, but it is probably the best I can do as an initial statement. Because it will no doubt generate questions (or even objections) in the minds of others, however, everyone should feel free to ask additional questions or to raise objections to it. Thank you, Father Kimel, for raising an important question.

-Tom

LikeLike

What I’m hearing is: God cannot guarantee that libertarian outcomes always unfold precisely as he desires, and so libertarian philosophers should accommodate their possible world semantics to this understanding of created agency.

The philosophical world needed to be convinced of this by Plantinga? It seems trivially true. But what one needs to bring into relation to one’s understanding of what possible or impossible for God when considering libertarian possible worlds is God’s freedom and abilities to bring into being that “initial state” required and then to sustain in existence those created powers necessary for the world’s free becoming. Things might go this way and might go that way given the kind of agency God gives. But this itself isn’t metaphysically impossible to God (unless of course one can show that it’s metaphysically impossible that God empower what he creates with such agency; if libertarian choice is metaphysically impossible, then descriptions of possible worlds including libertarian choices are in fact ‘impossible worlds’).

But assuming for the moment libertarian choice (and I don’t see that anyone’s defined it and suspect there are competing definitions at work in this and other threads) is coherent, the point is that total descriptions of libertarian possible worlds include a tacit qualification:

World-C is possible “where IF and only IF God freely creates the necessary initial state of libertarian agents, and IF and only IF all the freely chosen causal chains necessary to the world’s becoming the particular world in which Caesar crosses the Rubicon eventuate as needed.”

To say God can actualize World-C is to say God can do what God does in World-C which by definition already precludes his actualizing by divine fiat all the libertarian choices of World-C per its description. So to then describe God as being “incapable” of doing the latter is very like blaming God for being unable to be God as described in World-C (i.e., as God freely granting creatures a kind of agency God does not exhaustively determine), which seems philosophically confused.

TomB

LikeLike

Hello again, TomB:

You wrote: “What I’m hearing is: God cannot guarantee that libertarian outcomes always unfold precisely as he desires, and so libertarian philosophers should accommodate their possible world semantics to this understanding of created agency. You then went on to comment: “The philosophical world needed to be convinced of this by Plantinga? It seems trivially true.”

Yes, that is often the way it goes in philosophy. When someone exposes clearly and decisively a widespread confusion, those who follow the argument are apt to say, “Gee, that’s just obvious. How could we not have seen it before?” I once had a professor in graduate school who liked to say that good philosophy is very boring, because the things that the best philosophers say are just right and, once said, very obvious. I disagreed with that observation because it ignores the important role that imagination and creativity can sometimes play in good philosophy. But the man did have a point about a lot of good philosophy.

Anyway, I can assure you that during my own undergraduate days virtually everyone assumed that God, if he should exist, could create (or make actual) any possible world he pleased. If one should doubt that this was the prevailing view at the time, one need only check out two articles that were widely anthologized throughout the latter half of the 20th Century: J. L. Mackie’s “Evil and Omnipotence” (first published in Mind, 1955) and H. J. McCloskey’s “God and Evil” (first published in Philosophical Quarterly, 1960). But even as late as 2007 John Beversluis tried to make me look like an idiot for, among other things, essentially defending Plantinga’s view. He thus wrote: “That is even more puzzling. How could God be ‘powerless’ to create a ‘logically consistent’ world? Since self-contradictory tasks are the only restrictions on Omnipotence and since the creation of a ‘logically consistent’ world involves no such task, what is the problem?” (See the second edition of C. S. Lewis and the Search for Rational Religion, p. 244). Ironically, I might have said the same thing during my own undergraduate days.

So even to this day, Leibniz’s Lapse, as Plantinga dubbed this mistake back in the 1970s, continues to be alive and well in some circles. To be consistent, however, an atheist must agree with Plantinga and disagree with Beversluis in this matter. For an atheist must hold that an uncreated universe is truly possible, and it is surely asking too much even of an omnipotent being that it have the power to create an uncreated universe. But in any event, I think your own interpretation quoted above is right on target.

Thanks for your comments.

-Tom

LikeLike

Jeff, I have restrained from saying anything, as I didn’t want to interfere with the very interesting conversation you are having with Tom Talbott; but I do want to comment on something you state above: “I suppose, for arguments sake, I think it very likely that there is one possible in world in which just 5 free people are created and they all come to faith, but in this case I think God would be giving up other goods which God desires.” This echoes two sentences in your article: “Yes of course the salvation of all is a great good, but universal salvation may make other great goods impossible. … In short: though God may want the salvation of all, there may be other compelling goods that would give God reason to prefer a different kind of world.”

As I noted in my article, I have questions about the Molinist construal of divine foreknowledge, but for the purpose of argument, let’s assume that Molinism is coherent and that God foresees all possible worlds and chooses one to actualize. You appear to believe that God has deliberately chosen a world in which people do reject him and are thus eventually annihilated in divine judgment. In other words, God is the ultimate cause of evil and the Fall.

As an Eastern Orthodox Christian, I reject this most emphatically. It touches upon the very heart of the gospel. Unless requested, I will not elaborate further, as I would probably just end up repeating what I wrote in my earlier article. I find this so serious that I would out walk out any church service if a preacher were to ever say something like that.

Needless to say, I believe this to be a decisive objection to the Molinist construal of divine foreknowledge.

LikeLike

Jeff, if I am wrong that the Molinist position implies God’s ultimate responsibility for evil, sin and death, I am happy to be corrected.

LikeLike

Hello again, Jeff:

Thanks for responding to my query concerning your own understanding of a possible world. That was helpful. In keeping with my desire, expressed in my previous response, to proceed very slowly, taking one tiny baby step at a time, I’m going to restrict my attention here to the following sentence: “By ‘Possible Worlds’ I am saying ‘a state of affairs God could have actualized.’”

Now as I’m sure you will agree, a possible world is not just any state of affairs but a very large one, what Plantinga would call a maximal state of affairs. As he puts it in God, Freedom, and Evil, “If A is a possible world, then it says something about everything; every state of affairs S is either included in or precluded by it” (p. 36). And when you say that “God could have actualized” some state of affairs, you are, I presume, using the notoriously ambiguous term “could” in the sense of having the power to do something. All of which suggests:

Does represent accurately your own conception? If so, then you have indeed collapsed the idea of a possible world into that of a feasible world, as some Molinists understand the latter idea. That, of course, is your prerogative, since we are all free to define our own terms in any way we please. But we must also use our own terms consistently, and so my next question concerns the matter of consistent usage.

represent accurately your own conception? If so, then you have indeed collapsed the idea of a possible world into that of a feasible world, as some Molinists understand the latter idea. That, of course, is your prerogative, since we are all free to define our own terms in any way we please. But we must also use our own terms consistently, and so my next question concerns the matter of consistent usage.