by Brian C. Moore, Ph.D.

Jesus and the disciples get into a boat to cross the lake. In transit, Jesus sleeps and the wind picks up, a storm rages. This is an intimation of Christ in the tomb, and the apostles are paralyzed in terror. They awake the Master, who is Lord of life. And Jesus rebukes the wind and water as easily as you or I might move a limb. The disciples are relieved, yet fearful. What have they got themselves into, taking up with this fellah? This is no small thing, though I can imagine a certain type trying to subsume this into a general category of wonder worker, make it just another case of sympathetic magic. Too bad, because it’s not that at all. Nor is it simply imperious, for there is a thread in this action that goes all the way back to the Annunciation, to Mary’s yes, this yes that Molly Bloom will echo millennia later, that all women echo when they affirm life, nestle it, give it a home. (Oh, I see this equation will distress some. I refer to analogical levels of being. Mary’s assent is primal, wisdom’s smile, but from it all loving relations participate—and if this is too much for you, leave it as ravings and God be with you.) Yet I say that reality is nuptial and God’s command is more a dance of partners than a mechanical setting in motion, the work of clockwork automatons. Lose this and wonder vanishes. Curiosity is not wonder. It can devolve into a gelid objectivity, the kind that pulls the wings off of flies to see how things tick. One sees this, for instance, in the ghastly consequences of Cartesian mechanism:

During a visit from Fontanelle, Abbé Trublet records that Malebranche kicked a pregnant dog and when Fontanelle cried out in compassion Malebranche rebuked him saying ‘What? Don’t you understand that it doesn’t feel anything?’ Other Cartesian cruelties were more systematic: They administered beatings to dogs with perfect indifference, and made fun of those who pitied the creatures as if they had felt pain. They said that animals were clocks; that the cries they emitted when struck, were only the noise of a little spring which had been touched, but that the whole body was without feeling. They nailed poor animals up on boards by their four paws to vivisect them and see the circulation of the blood which was a great subject of conversation (quoted in David L. Clough, On Animals, pp. 139 – 140).

If one researches how animals are treated in agribusiness or the routine cruelty and redundancy of testing done on animals for cosmetics and the pharmaceutical industry, it will become evident that a particular stance towards nature is not a mere episodic transgression of a past historical era. And if one grants a kind of crude brutality to the curiosity of early modernity, but then asserts a utilitarian value to our modern practices—and there may be such—it is still a move that presupposes a desacralized nature. It accepts as axiomatic a logic in which usefulness to human life validates the ethical correctness of such practices. Although in order to make this ethical claim, untroubled pragmatism must first deny any connection between the animal and a sustaining divine realm that would grant worth to the beasts.

“Disenchantment is a sign of stupidity,” exclaimed that thundering child, Bernanos. (Native Americans would have killed the buffalo for meat and furs, but the transaction was enacted within an ethos of prayer, in which gratitude was extended to the buffalo. The animal was not treated as a neutral object, a “standing reserve” for future technological manipulation.) And if one wants to see in all this a romanticization, I think there is still much truth in it. Aside from that, there is no doubt that the modern approach is a certain theoretical relation to nature that is not merely a product of unprecedented power, but the working out of a chosen spiritual mode of seeing and living. Wordsworth’s familiar lines have been oft repeated: “we murder to dissect.”

Edward Feser recently took issue with David Bentley Hart’s ruminations upon the possibility of an afterlife for one’s pets. Feser thinks that since the conscious states of animals are somatic through and through, once the body dies into corruption, there is simply nothing left to make intelligible the notion of carrying some sort of beastly spiritual identity into an afterlife. As Feser laconically concludes, “Fido’s death is thus the end of Fido.” The only reason humankind is exempt from such extinction is that human souls exhibit an intellectual capacity that transcends physical corporeality. There are, frankly, all kinds of problems with this analysis, including a nearly positivist truncation of reality to the dimensions of fallen time to a failure to properly think through the embodied nature of intellect. Worse, it treats this love as a merely transient emotional transaction and not as something ontological, bearing epistemological implications. It also imagines that the dearness of a beloved animal to a human person somehow exceeds the love of God for his creation. It excludes them from the triumph of the new creation in which the tears of the old world are rendered otiose not by mere forgetfulness or blithe acceptance, but by wondrous, playful renewal. Certainly, Feser’s exasperated impatience with what he can only interpret as sentimental refusal to face metaphysical facts betrays an anemic imagination, as well as perhaps a tendency to forget that Aquinas inaugurated a particular mode of inquiry, rather than fully comprehended realities.

Edward Feser recently took issue with David Bentley Hart’s ruminations upon the possibility of an afterlife for one’s pets. Feser thinks that since the conscious states of animals are somatic through and through, once the body dies into corruption, there is simply nothing left to make intelligible the notion of carrying some sort of beastly spiritual identity into an afterlife. As Feser laconically concludes, “Fido’s death is thus the end of Fido.” The only reason humankind is exempt from such extinction is that human souls exhibit an intellectual capacity that transcends physical corporeality. There are, frankly, all kinds of problems with this analysis, including a nearly positivist truncation of reality to the dimensions of fallen time to a failure to properly think through the embodied nature of intellect. Worse, it treats this love as a merely transient emotional transaction and not as something ontological, bearing epistemological implications. It also imagines that the dearness of a beloved animal to a human person somehow exceeds the love of God for his creation. It excludes them from the triumph of the new creation in which the tears of the old world are rendered otiose not by mere forgetfulness or blithe acceptance, but by wondrous, playful renewal. Certainly, Feser’s exasperated impatience with what he can only interpret as sentimental refusal to face metaphysical facts betrays an anemic imagination, as well as perhaps a tendency to forget that Aquinas inaugurated a particular mode of inquiry, rather than fully comprehended realities.

Those who treat the question of the afterlife of animals as intellectually obtuse or as a sentimental quibble, though understandable, fit only for children, have forgotten that to such is given the kingdom of God. Not only is it condescending, it misses the real importance embedded in the child-like concern. Feser’s view relegates animal suffering to inconsequentiality—even if one were to find some justification in terms of nature or mankind, it treats the unique pain, suffering, and death of the animal as nugatory in terms of justice. If Fido is indeed permanently lost to the Never, the singularity of Fido must be treated as loss simply. One can, naturally, deny the singularity of Fido, but this is more in line with Aristotle than a Christian understanding of creation. Beyond this, it fails to grant deep seriousness and significance to the love human beings have for animals and that animals have for us. Consider Hachiko, an Akita dog made famous for his loyalty. For a decade after the death of his master, he continued to come each day to await his master at Shibuya station in Tokyo. Or ponder the poignant case of two herds of wild South African elephants who mysteriously made their way through miles of Zululand bush to the gates of Lawrence Anthony’s Thula Thula game reserve shortly after the death of the “elephant whisperer.” For two days they remained in tribute to the man who had lived amongst them and shown them compassion.

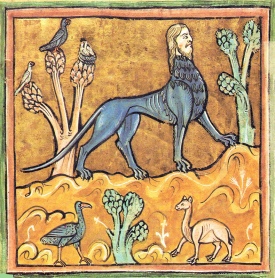

One can, of course, dismiss all this as anthropomorphic projection. Feser demurs that one can allow for some psychic, emotive reality beyond Cartesian mechanism in the beasts without engaging in the kind of personification animal lovers are prone to. We can agree that animals do not have conceptual knowledge. With apologies to Koko the gorilla, the beasts do not reason or exhibit language except in analogous forms. Walker Percy tried to draw attention to Charles S. Peirce’s triadic semiotic. Only man has a world that transcends an environment. Only man can think a world where he does not exist. The animal remains locked into an environment of dyadic interaction. Once the banana has disappeared, Koko does not spend time pondering the mysteries of banana existence, let alone her own. All this is true. Nonetheless, close observation of animals reveals surprising depths of feeling and nuances of behavior. Beyond the obvious struggles for survival, acts of unsuspected kindness and cruelty that nears the edges of malice are both discoverable in nature. It is a world too rich to be tied to human complacency. Aquinas remarked that no one has comprehended so much as a gnat. Have a look some time at Blake’s portrait of the ghost of a flea.

While no human knows what it is to be or feel like a bear or a dolphin, it is also true that human realities are mysteriously linked to those of other creatures. Adamic naming could have presaged further development in the animal world. The serpent’s speech may indicate as some have speculated that there was a close connection between beasts and their angelic archetypes. (Let us propose without argument that such a metaphysics is not merely whimsical.) A distinguishable, but not separate unity lends plausibility to serpentine speech. If one prefers, no such reality is indicated. The myth incorporates folkloric personifications of nature in order to provide an aetiology for evil and death, among other things. In either case (and I have deliberately chosen polarized options), the linkage of beasts with language suggests 1) that all creatures through their acts communicate something of their essence, and 2) that mankind is drawn to a horizon in which the opacity of nature gives way to a more open, dramatic dialogue.

Anthropomorphism may indulge in spurious projection. It may also discern an inchoate germ of freedom—a genuine human-like dimension to the animals because the animals truly derive from a human (Christic) foundation. Speculatively, it may have been part of Adam’s calling as priest of creation to bring the beasts to speech, i.e., to draw them out of dyadic imprisonment, beyond their natural limits. Everyone is familiar with Paul’s cryptic remarks: For now, “all creation groaneth.” The loving relations between humans and animals here and now are glimpses and anticipations of far greater amity in the future kingdom.

Anthropomorphism may indulge in spurious projection. It may also discern an inchoate germ of freedom—a genuine human-like dimension to the animals because the animals truly derive from a human (Christic) foundation. Speculatively, it may have been part of Adam’s calling as priest of creation to bring the beasts to speech, i.e., to draw them out of dyadic imprisonment, beyond their natural limits. Everyone is familiar with Paul’s cryptic remarks: For now, “all creation groaneth.” The loving relations between humans and animals here and now are glimpses and anticipations of far greater amity in the future kingdom.

Note: it does not matter that the beasts only analogously approach human “reason” and that their love is not “intellectual.” That does not mean it isn’t love. All love, even the humblest relation between iron and a magnet is submerged participation in Triune life. What is distinctive about human love is that it can come to intellectually understand the mystery of love, which is also the mystery of knowledge. We do not know what might flower from the least seed, but the perfection will be a radiation of love, not a sturdy “common sense” causality destined for nothingness. Such an extrinsic causality fails to reckon on the dimensional thickness of reality, for always the dynamic, transient “stable instability” of the perceptible world is only because of eternity. In Bulgakov’s terms, creaturely Sophia seeks through becoming to realize the promise of divine Sophia. Fido will not vanish into the Never, because Fido would not have entered the world of becoming at all if he did not have a perduring eternal root. Czeslaw Milosz’s poetic sensibility has grasped the point:

If you take some of my poems which are among those available in English, you will find a very erotic attitude towards reality, towards simple things: amazement, for instance, for the innumerable and boundless substance of the earth—the scent of pine, the hue of fire, the white frost, the dance of cranes: that everything is intelligent and probably eternal, what I have seen and what I have heard, everything as it was. (Conversations, pp. 26 – 27).

Or, as Dionysius the Aeropagite said long ago, “The beauties of the phenomenal world are representations . . . of the invisible loveliness.” (Rank Platonism laments the Thomist. Well, there are all sorts of Thomists, even a few who appreciate the Christian Platonism of Thomas.)

“Jesus is the first name of a new language of mankind,” wrote Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy, that eccentric, prescient polymath. What is it to speak this new language? It is the Logos made Flesh; it is creation understood as always coming from and moving towards the body of Christ. Even fallen time is never without its root in eternity. Those who imagine that a sand pebble, a water lily, the beasts of the field are merely transient creatures of the day, expiring with their bodies exhibit coldness of heart, narrowness of vision, no matter how exemplary they suppose their metaphysics. “For everything that lives is holy,” said William Blake.

Look with the eye of contemplation on the most dissipated tabby of the streets, and you will discern the celestial quality of life set like an aureole about his tattered ears (Evelyn Underhill, quoted in Emilie Griffin, Clinging, p. 69).

“The eyes see in things only what it looks for and it looks only for what it already has in mind . . . As one is, so one will see the world” (P. Sherrard). “Ears and eyes are bad witnesses for those with barbarian souls” (Herakleitos). John Zizioulas articulates what he calls the Eucharistic conception of truth: “the Christ-truth exists for the life of the whole cosmos . . . the deification which Christ brings, the communion with the divine life (II Peter 1:4), extends to ‘all creation’ and not just to humanity” (Being as Communion, p. 120). For those with eyes sharpened by love, Sherrard’s words will not be dismissed as foggy emotivism, for they are meticulous in metaphysical precision:

So long as we fail to realize that this view of nature is a complete misconception, and that what we call our empirical and experimental knowledge of facts is itself an essential part of our ignorance, we will continue to desecrate the earth and everything on it without even the slightest awareness of what we are doing or why we are doing it. And we will go on failing to realize that this view of nature is a complete misconception for so long as we also fail to realize that the words of Christ, “In so far as you did it to one of the least of these my kindred, you did it to me” (Mt. 25:40), apply not simply to his human kindred, but to every natural form of life and being. For every natural form of life and being, down to the most humble, is the life and being of God (Sherrard, Christianity, p. 220).

It is no surprise that Feser groups glib acceptance of animal annihilation in with a breezy dismissal of sexual love from eternity. Though it is easy to belittle concern for these matters as the preoccupations of the hoi polloi unable to comprehend divine things, I believe that it is more true to say that such a repudiation of fundamental human longings is based on a purely superficial reading of biblical texts, along with either despair of the earth or a vulgar reading of human desire unable to discover an unbroken connection between elemental desire and eschatological fulfillment. For Feser and his brethren, the fate of a kitten or the life and death of a plesiosaurus must be like Africa for Hegel, outside history. His rationalizing aplomb that makes the natural world a frangible loss made acceptable as the cost of providing a context for intellectual souls to journey beyond the earth is eerily similar to pagan economics. I do not care, frankly, if my conjectures strain the credulity of many or if they will find reason in their syllogisms to mock my intuitions as risible. I maintain that nothing and no one is outside the Body of Christ, that the consigning of a single pebble to oblivion represents a defeat of God’s justice, casts aspersions upon God’s love, and diminishes our freedom.

Wonderful, one of the best meditations, Brian.

Do you know T H White’s take on the Matter of Britain, his superb novel The Once and Future King? Perhaps my favorite moment in that book comes fairly early when Merlin, in order to thoroughly educate Arthur, turns him into various animals. I remember reading that the first time and thinking, yes, that would be the ideal education, pity we can’t manage it. And yet, in a way, we can, for White thought of it and put it in a book in a substantial way. So this plays into what you’ve written elsewhere about art: it is sine qua non for a genuinely cosmological imagination.

LikeLike

I have not read T H White in many years, Jonathan, but I still recollect his book, particularly the education of Wart, which is the strongest part of the novel in my view. I agree that through the imagination we are able to go beyond merely descriptive mimesis. Further, I would claim that the modern epistemological turn that only countenances “representation” is a mistake. If our knowledge is not merely a simulacrum of reality, but actually achieves identity through participation as an older, Platonic metaphysic and a realism of a Thomist kind would assert, then we are not locked into a purely extrinsic “copying” of what is out there. A purely “correlative” understanding of truth is based on trying to get our inner impressions to match as closely as possible an outer reality. But all that is too superficial and does not really countenance the “community of being” in which relations are constitutive and outside other enters into real communion with the interior of the spirit.

Hence, poetry is not as modern philistines think, an extrinsic ornamentation of merely decorative interest. The imagination makes discoveries and continues to make discoveries, because the creature is rooted in the infinite agapeic depths of a loving and creative God.

LikeLike

Thanks, Brian.

I know some Orthodox saints did not take kindly to all the sentimentality that is shown toward animals – over-anthropomorphizing them, relating to one’s pets as “my babies” etc. I agree that attempting to strip an animal of its own nature and relate to it as a human is a mistake, but more of ignorance, or perhaps some inner pain, than anything else. Cruelty to animals bespeaks a truly horrifying brokenness and suffering within a person. Other saints were loved by animals, and I have always found myself being drawn to them for their help in prayer. If Christ is drawing all creation toward union with himself, as Fr Stephen Freeman writes and as we see repeatedly in the NT, then that must include animals as well.

We are told through the Psalmist “No good thing will he withhold from those who walk uprightly” and “Those who seek the Lord lack no good thing.” A right relationship with animals is a good thing, and I can’t imagine Paradise without them, especially my faithful pets. Contrary to the anthropomorphization by people who seem to center their lives around their pets in an unhealthy way, I’ve watched my dogs and cats become “doggier” and “cattier” over the years with what I hope has been the appropriate exchange of love between us.

I do not use cosmetics or other personal products that have been tested on animals. I strive to eat less meat, and as far as is possible for me to know, I only buy meat and eggs from animals that were humanely raised. That’s fairly easy to do where I live (my county is the first in the country to ban GMOs in the ag setting). Wish other people would use the power of the marketplace to nudge people toward change in this direction.

Dana

LikeLike

Thank you for your good thoughts, Dana.

I think we should do what we can to show kindness and care towards creation.

Obviously, one must use prudential discernment. Your reflections on how our animals realize their own particular nature through good interaction with us is something I strongly believe in, though there are animal activists who almost see any human interaction as somehow corrupting. For many in the environmentalist movement, being human is the Original Sin.

LikeLike

Alas, the extremism you speak of is all too real, and it is heinous. For instance, this is an actual thing: http://www.vhemt.org/

LikeLike

I can understand disgust with humanity setting in, but that kind of repudiation of human being is a flight from love, meaning, and true compassion. It’s really an act of cowardice and I suspect Satanically inspired.

LikeLike

I have mixed feelings on this. We’re to expect wooly mammoths, saber tooth tigers, and T-Rex’s in heaven?

LikeLike

Tom, you’re going to have so much fun with your pet Allosaurus! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

There’s really nothing like relaxing by the hearth on a chilly autumn evening with six tons of wooly mammoth curled up at your feet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Bulgakov speculated that some creatures will translate into the eschaton in forms recognizable to us, whilst others would require more transformation to enter a renewed universe. I have always understood the lion laying down with the lamb to be a shorthand symbol for the kingdom of God allowing for a flourishing peace at every level of existence. This is something we can only anticipate imaginatively in a mirror darkly and through poetic images. However, if the logic of Triune love in the light of creatio ex nihilo is properly thought out, as I’ve argued for in several of these meditations, I do not see how any created being could be rendered superfluous.

There’s an interesting moment, btw, in Malick’s Tree of Life, where grace appears in the interaction of several dinosaurs — violence is forestalled by a mysterious charity.

Then again, I expect the entire universe to be remade. All those galaxies out there aren’t there for nothing. Pretty sure Tom Talbott has some nice speculation in this direction in The Inescapable Love of God.

LikeLike