[This article has been revised and republished under the same title on 1 December 2021]

“I am not going to try to prove the doctrine [of hell] tolerable,” writes C. S. Lewis in his book The Problem of Pain. “Let us make no mistake; it is not tolerable. But I think the doctrine can be shown to be moral.” Fr Lawrence Farley agrees. In “The Morality of Gehenna,” he offers an apology for eternal damnation. Making the doctrine “palatable is beyond my power or intention,” he writes, but perhaps it can be shown to be moral and just and thus reconcilable with belief in the love of God … or perhaps not.

One immediately notes a difference in Fr Lawrence’s construal of eternal damnation. In his preceding article, “Christian Universalism,” Fr Lawrence claims that Holy Scripture teaches a retributive model of damnation: “God is the judge of all the earth, and his punishing judgment and severity falls upon those who rebel against righteousness.” Jesus’ teaching on Gehenna but represents the eternalization of the divine retribution. Many of the early Church Fathers, ranging from St John Chrysostom to St Augustine, can be cited in support of this interpretation. In “The Morality of Gehenna,” however, Fr Lawrence quietly moves from a retributive model of damnation, in which God is the active agent of punishment, to a libertarian model, in which God ratifies the fundamental orientation of the self-damned and abandons them to the interior consequences of their sins. I do not object to this shift (who wouldn’t prefer The Great Divorce to “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God”?), but I do have to ask: What is its biblical grounding? On what basis does one override the “clear” biblical witness to retributive damnation (a witness so strong, the author has told us, that we must dismiss universalist proposals) and affirm a view that lacks explicit biblical support? (Might we be seeing a bit of philosophy and theological reasoning at work here?) I’m sure scriptural verses on behalf of the libertarian model can be cited, just as one can provide them for universal repentance; yet Fr Lawrence’s stated methodology requires that the less certain texts be interpreted through the dominant, unambiguous ones. Once again we are brought into the thicket of hermeneutics. Neither biblicism nor patristicism can resolve the challenge.

(For a comparative analysis of the principal models of damnation, see Jerry Walls, Hell: The Logic of Damnation, as well as the contributions of Jonathan Kvanvig and Thomas Talbott to the online Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.)

The libertarian model of damnation became the dominant understanding of eternal damnation in the second-half of the twentieth century. While one can still find proponents of the retributive model, their numbers are growing fewer. Across the denominational board, Christians have come to believe that eternal retribution is incompatible with the infinitely loving Father as revealed in and by the incarnate Son. George MacDonald’s meditation upon divine justice seems prophetic now: “I believe that justice and mercy are simply one and the same thing; without justice to the full there can be no mercy, and without mercy to the full there can be no justice.” How then do we justify eternal damnation? By reinterpreting damnation as the creature’s irrevocable act of self-alienation from his Creator. The reprobate choose perdition. God does not damn; man damns himself. The Father eternally offers sinners mercy and forgiveness; but those who exist in the state of damnation perpetually refuse the offer. In the oft-quoted words of Lewis: “I willingly believe that the damned are, in one sense, successful, rebels to the end; that the doors of hell are locked on the inside.”

But is this free-will construal of eternal damnation rationally coherent? I long thought that it was. The Great Divorce is one of my favorite spiritual books, and I have often used its arguments and stories in my preaching and catechesis. Yet the libertarian position has its weaknesses. Philosopher Thomas Talbott has subjected the libertarian model to incisive critique in several peer-reviewed essays, as well as in his book The Inescapable Love of God. His book is essential reading. I would even go so far as to declare that no one should publicly reject the universalist hope until they have first wrestled with and answered his arguments. Talbott’s argumentation is well complemented by the rigorous philosophical analysis of John Kronen and Eric Reitan in God’s Final Victory. The latter work can be hard sledding for those untrained in analytic philosophy, but Talbott’s book is wonderfully accessible.

Can you imagine a human being eternally rejecting God?

“Absolutely,” you reply. “I do it all the time.”

Now let’s add misery into the equation. Can you imagine a human being freely choosing eternal misery and intolerable suffering over God?

Now matters become a bit more complicated. Will you not do just about anything to avoid pain and unhappiness? You might temporarily sacrifice lesser goods in order to acquire what you believe to be a greater good (as a jewel thief might invest a great deal of time, energy, and money preparing for a lucrative heist); but what if there’s no payoff, only interminable, ever-increasing torment?

“Yes, I’m forced to admit that doesn’t seem to make much sense. I always prefer happiness to unhappiness. That’s why I choose to sin. I want what I want and I want it now. I don’t want to wait for the future happiness the preacher promises me. I am satisfaction-driven. Even when I am spiteful to another, it’s because it gives me some degree of perverted pleasure. So no, I suppose I can’t envision myself freely choosing the fire of Gehenna.”

And now we come to the critical Christian point: God, and God alone, is our consummate happiness, our supreme Good. We were created by God for God. While we may search for our happiness in temporal goods, while we may confuse apparent goods for real goods, while we may be tragically ignorant of the fundamental truth of our ultimate fulfillment, we are always searching for the God and will never find abiding happiness and peace except through union with him. Lewis puts it this way:

What Satan put into the heads of our remote ancestors was the idea that they ‘could be like Gods’—could set up on their own as if they had created themselves—be their own masters—invent some sort of happiness for themselves outside God, apart from God. And out of that hopeless attempt has come nearly all that we call human history—money, poverty, ambition, war, prostitution, classes, empires, slavery—the long, terrible story of man trying to find something other than God to make Him happy. The reason why it can never succeed is this. God made us: invented us as man made the engine. A car is made to run on gasoline, and it would not run properly on anything else. Now God designed the human machine to run on Himself. He Himself is the fuel our spirits were designed to feed on. There is no other. That is why it is just no good asking God to make us happy in our own way without bothering about religion. God cannot give us a happiness apart from Himself, because it is not there. There is no such thing. (Mere Christianity)

The Father has created us to enjoy him forever in the communion of the Son and Holy Spirit.

Given that God is our transcendent and perfect Good, can you imagine a genuinely informed human being freely choosing utter misery over eternal happiness with God? Can you imagine yourself doing so?

I respectfully suggest you cannot, not really. You might be able to imagine yourself doing so under conditions of ignorance, delusion, psychological disorder, and enslavement to the passions—all of which characterize our fallen existence—but in their absence you cannot imagine yourself choosing absolute, unabating, unrelievable misery, not if you possessed the freedom to choose otherwise. It would make no sense—a choice made for no reason or motive whatsoever. Talbott puts it this way:

Let us now begin to explore what it might mean to say that someone freely rejects God forever. Is there in fact a coherent meaning here? Religious people sometimes speak of God as if he were just another human magistrate who seeks his own glory and requires obedience for its own sake; they even speak as if we might reject the Creator and Father of our souls without rejecting ourselves, oppose his will for our lives without opposing, schizophrenically perhaps, our own will for our lives. [William Lane] Craig thus speaks of the “stubborn refusal to submit one’s will to that of another.” But if God is our loving Creator, then he wills for us exactly what, at the most fundamental level, we want for ourselves; he wills that we should experience supreme happiness, that our deepest yearnings should be satisfied, and that all of our needs should be met. (The Inescapable Love of God [2nd ed.], p. 172; my emphasis)

The good that we desire for ourselves and the good God desires for us are identical! When properly formulated and understood, therefore, definitive rejection of God ironically turns out to be the most “selfless” act conceivable—and that is why it is inconceivable. It would be to deny our deepest and truest self. It requires us to choose privation for privation’s sake, to choose misery for misery’s sake, to choose evil for evil’s sake.

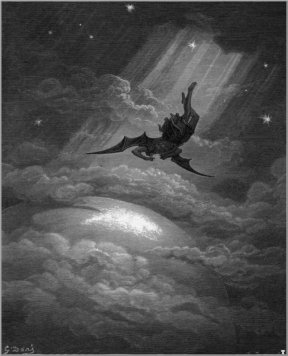

But, replies Fr Lawrence, that is precisely what the Devil did! Hence all of this philosophical speculation proves empty. We know of at least one rational being who did the rationally impossible: “In the devil we find an abyss of unreason, a perverse fixity and commitment to rebellion, even when it is known to be futile and self-defeating and leads to damnation.” Lucifer was given a direct vision of God at the moment of his creation, and yet he rejected God and became the Satan. How then can anyone posit the inconceivability of self-damnation? “The sad truth,” Fr Lawrence concludes, “is that the human person is quite capable of misusing the inherently purposive, teleological, primordially oriented toward the good power of the will and perverting it into something entirely different.”

But, replies Fr Lawrence, that is precisely what the Devil did! Hence all of this philosophical speculation proves empty. We know of at least one rational being who did the rationally impossible: “In the devil we find an abyss of unreason, a perverse fixity and commitment to rebellion, even when it is known to be futile and self-defeating and leads to damnation.” Lucifer was given a direct vision of God at the moment of his creation, and yet he rejected God and became the Satan. How then can anyone posit the inconceivability of self-damnation? “The sad truth,” Fr Lawrence concludes, “is that the human person is quite capable of misusing the inherently purposive, teleological, primordially oriented toward the good power of the will and perverting it into something entirely different.”

This counter-argument, however, is purely speculative. God has not revealed to us the origin of the demonic fall. We know very little about the unholy spirits, beyond the fact that they are our enemy and must be renounced. Of course, that has not stopped theologians from speculating about their rebellion, but these speculations are predicated on the prior dogmatic conviction of eternal perdition—and it is this conviction that we are debating. If we know that the damned have freely chosen damnation, then we will naturally seek an explanation. And so we posit the incomprehensible mystery of primaeval evil. Once upon a time, the greatest of the archangels knew the goodness of God with crystalline clarity, knew God as his supreme and only Good, knew God as infinite and unconditional Love; and yet, despite this perfect knowledge, he freely rejected eternal bliss and instead chose intolerable torment. But all of this is speculation and myth. God has not disclosed to us the whys and wherefores of the angelic rebellion. Paradise Lost is not Holy Scripture (see Talbott’s discussion of Milton’s portrayal of Satan, pp. 173-175; also see my article “Rational Freedom and the Incoherence of Satan“). Perhaps, just perhaps, in a way we cannot understand, God gave the angelic spirits an epistemic distance analogous to that which he appears to have given Adam and Eve for the development of their personhood—just perhaps. In any case, the claim that rational beings can freely reject the perfect Good when experienced in immediate vision must be deemed implausible.

In his essay “God, Creation, and Evil,” David B. Hart discusses free will and argues for the impossibility of a definitive, irreversible decision against God. Man is created in the Image of God and cannot destroy his transcendental orientation:

But, on any cogent account, free will is a power inherently purposive, teleological, primordially oriented toward the good, and shaped by that transcendental appetite to the degree that a soul can recognize the good for what it is. No one can freely will the evil as evil; one can take the evil for the good, but that does not alter the prior transcendental orientation that wakens all desire. To see the good truly is to desire it insatiably; not to desire it is not to have known it, and so never to have been free to choose it. (p. 10)

Hart’s argument is not identical to Talbott’s, but both concur that the human being is intrinsically ordered to the Good. In reply to this argument, Fr Lawrence remarks: “Here the philosopher smacks up against the exegete. Philosophical arguments about what the human will is or is not capable of are interesting, but must take an epistemological backseat to the teaching of Scripture—and the Fathers would agree.” This simply will not do. Yes, Dr Hart is presenting a sophisticated, reasoned argument, but it is an argument grounded in the Bible and patristic metaphysics. Whenever we exegete Holy Scripture, we are doing philosophy, no matter how rudimentary or unselfconscious. To think we can cordon ourselves off from metaphysics, even in the simplest interpretive act, is naïve. The only question is whether we are doing good philosophy or bad philosophy.

Fr.,

I’ve held belief in a “synergistic” condemnation prior to becoming Orthodox. When I embraced synergistic salvation, I embraced synergistic damnation as well. For instance, in Scripture both salvation and damnation are described as God’s hands: Jn. 10:28-29 salvation; Heb. 10:31 damnation. Additionally, both conditions are described as His presence: Acts 3:20; Rev. 14:10.

I was overjoyed when I found this interpretation in the Fathers. Chrysostom and St. Maximus both affirm that men can’t get to Hades and Hell by their own power. St. Gregory of Nyssa said that the chasm that the Rich Man couldn’t cross was in his own heart.

Even in the OT, the same Sun enlivens and burns:

“For behold, the day is coming, burning like an oven, when all the arrogant and all evildoers will be stubble. The day that is coming shall set them ablaze, says the Lord of hosts, so that it will leave them neither root nor branch. But for you who fear my name, the sun of righteousness shall rise with healing in its wings. You shall go out leaping like calves from the stall. And you shall tread down the wicked, for they will be ashes under the soles of your feet, on the day when I act, says the Lord of hosts.”

Malachi 4:1-3 ESV

LikeLike

Maximus, why do you think that anything in this article denies synergism? Re-read it again, and I think you’ll see that it’s about the conditions for rational freedom and our divinely-given desire for the Good. The human being is not free if he finds himself jumping off a cliff to his doom for no reason whatsoever—at least that is what I would argue.

But a different understanding of freedom arose with Ockham in the late middle ages, what has been described as a “freedom of indifference,” which simply amounts to individualistic autonomy. But I don’t think St Maximus can be recruited for this view. But I acknowledge that autonomy is what many Christians today, including Orthodox, seem to mean when they speak of synergism or cooperation with God.

LikeLike

It seems to me that the problem is an underlying Platonism that assumes that seeing God is loving Him. When one takes a stance more like critical realism it is entirely plausible to think of Hell as an unending spiral of self-deception. People who do not believe continue to deceive themselves and to interpret their experiences in a way that validates their self-deception. It is akin to the gambling addict who thinks the next coin in the slot machine will be the big winner.

LikeLike

Interesting suggestion, Carey. Could you elaborate further for us, please.

LikeLike

How might this relate to character at the end of Charles Williams’s Descent into Hell, and to the reaction of some of the Dwarves near the end of C.S. Lewis’s Last Battle? And, again, to Eric Voegelin’s characterization in Science, Politics and Gnosticism of Nietzsche’s approach in terms of “demonic mendacity”?

Might one speak here of possible questions of a ‘gradual irreparabality’ and/or a ‘voluntary irreparability’ of conscious, volitional creatures? An eventually irreversible occlusion?

But, it is possible for God so to create beyond His gracious, miraculous intervention?

If so why would God actualize that possibility?

If not, why would God choose not lovingly to intervene?

LikeLike

Descent into Hell is a terrifying story: it depicts the incremental process of damnation that is existential possibility for all of us.

And I agree with you, why would the God of love actualize a world in which the objects of his love could so barricade themselves against him that even he could not penetrate the egoistic walls of perdition? In fact, I’m not even sure that it makes sense. It sounds like the question, Can God make a rock that even he could not lift?

LikeLike

Hi Carey,

I’m trying to understand your example of the gambling addict.

First, are you imagining a gambler who has an endless supply of money and therefore never experiences the kind of financial disaster and personal misery that might persuade a minimally rational person to seek treatment for his or her compulsive behavior? If so, then the example seems to me a tad unrealistic; and if not, then the gambling addict seems to illustrate, contrary to your apparent intention, how the disastrous consequences of acting upon an illusion can sometimes shatter it to pieces. If I deceive myself into believing that I have the skill to ski down a treacherous slope and act upon it, for example, a fall and a broken leg (or a series of similar disasters on consecutive occasions) will presumably shatter that illusion—unless, of course, I am too irrational to qualify as a free moral agent.

Second, are you supposing that, no matter how compulsive and irrational the gambling addict’s behavior becomes, he or she remains morally responsible for that behavior? If so, why? If not, then how could the damned be morally responsible for “an unending spiral of self-deception” that eventually becomes utterly irrational? Would a schizophrenic young man who believes his loving mother to be a sinister space alien who has devoured his real mother be morally responsible for having killed her?

Thanks for an important contribution to the discussion.

-Tom

LikeLike

It seems to me that Fr. Lawrence is doing the very thing he accuses David B. Hart of doing? Must not his own philosophical conception of “the sovereignty of the human will” (his words) and of a person’s “own eternally-fixed will” also “take an epistemological backseat to the teaching of Scripture”? Where, after all, does Scripture speak of the sovereignty of the human will?

LikeLike

Fr.

Nothing in your articles ever deny freedom. I just sought to demonstrate that it’s not “God damnation OR self-damnation”; it’s both. And both are scriptural, and it does not have to mean that Fr. Lawrence utilized a philosophical shift to emphasize one aspect in one writing and the other in another.

LikeLike

Maximus,

I certainly agree (I think Fr Aidan would too) that there’s no ultimate contradiction between God’s will and our will when it comes to suffering the consequences of our choices (presently or eschatologically). God wills and sustains a world in which the abuse of freedom should suffer as it does, so your point is taken.

But as I understand Fr Aidan (and I might be wrong), I don’t think he set out to deny this; rather, he means to argue that within infernalism there is a tacit contradiction of this very principle in that infernalism has to suppose (philosophically mind you, for Scripture nowhere asserts it explicitly) that the created will can as a power God wills and sustains (which ‘sustaining’ as ‘willing’ is an Orthodox conviction) foreclose upon its powers all possibility of Godward movement. This places an ultimate symmetricality precisely where the doctrine of creation ex nihilo requires asymmetricality. How so? Because such ‘foreclosure’ cannot have God as its end/telos (since to have God as the end of your being is to have union with God as the possibility of your being). And to get that kind of absolute foreclosure one has to suppose God sustains in being that for which God does not will himself as end. And there’s a real problem here, for surely there is nothing beyond God’s willing himself as our end which constitutes the possibility of God’s actually being our end. So infernalists have to suppose God ceases willing himself as the end of that for which he imparts being—irrevocably so.

If the logic of creation out of nothing is maintained consistently, irrevocable foreclosure between God (as the uncreated summum bonum) and human being (as deriving the possibilities of its existence from God) is impossible. We are not self-existent—and therein lies the asymmetrical relationship between the limited but true liberty of choice we possess and the possibilities of being per se. The former cannot foreclose upon the latter. We cannot by any act of will constitute our ultimate possibilities of being. Given ex nihilo, nothing in us (which is just all God’s love endows us with) can determine whether or not what God wills for us is possible (and I emphasize “possible”). But this all has to be denied by infernalism which posits an inner contradiction within the very nature and will of God as the summum bonum willing possibilities that do not have him as their end. By willing to sustain in existence those irrevocably foreclosed upon all possibility of Godward movement, God ends up willing something other than himself as their final end, and that, Maximus, is a real ‘theological’ problem.

Tom

LikeLiked by 3 people

Maximus,

“Synergistic condemnation?”

This is ultimately a fancy way of saying that God is equally as complicit in damnation (as unending and irrevocable conscious torment) as in salvation, no? If a person were to “freely” will their own irrevocable demise, would even the tiniest divine preference in the direction of salvation make condemnation non-synergistic?

If one starts with God’s universal salvific will (very much at stake here), how could God possibly “synergistically condemn?” I would think that God only synergistically cooperates (when it comes to the eschatological destiny of creation) with that which He wills, with that which He wills being inseparable from His very nature.

This seems to be the hermeneutic of perdition on full display.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maximus, perhaps it might clarify our discussion by offering a brief statement of the two models:

1) Retributive model: at the Last Judgment, God will punish impenitent sinners, presumably by their works (Rom 2:6-8), with everlasting suffering and pain or, if one prefers, by depriving them of the Beatific Vision. This punishment is understood as the fulfillment of the divine justice: the wicked deserve their punishment. At this point God ceases to will their salvation. The governing image here is the court room.

St John Chrysostom (I think) and St Augustine (most assuredly) may be cited as representatives.

2) Libertarian model: at the Last Judgment, God will confirm the irrevocable rejection by impenitent sinners of his merciful offer of forgiveness, thereby permanently establishing them in their state of alienation, hatred, and torment. Typically the libertarian insists that God continues to desire the salvation of the damned, but because of their obduracy, his will is decisively frustrated.

St Maximus (possibly), St John of Damascus (possibly), and most modern Orthodox theologians may be cited cited as representatives.

How does the above sound? (Tom Talbott, how would you improve the above?)

The key difference, it seems to me, is that in the retributive model, God acts as judge and punisher, while in the libertarian model, God acts as ratifier of the fundamental decision of the reprobate, with the reprobate suffering the consequences of their irrevocable rejection (think “The River of Fire” by Kalomiros). Advocates of the libertarian model continue to employ the language of condemnation and punishment, but this language no longer quite means what it means in the retributive model. Thus the Damascene: “God does not punish anybody in the world to come, but each person makes himself capable of participation in God. Participation in God is joy; non-participation in Him is hell” (Against the Manichaeans PG 94). I suppose it might also be said that the damned deserve their plight, since they brought it upon themselves, but this is not what “deserving of punishment” means in the retributive or juridical model.

Now go back and reread Fr Lawrence Farley’s article “Christian Universalism.” Does it not at least sound as if he falls into the retributive camp, given the emphasis he puts on the punishment of sin? What parts of the article would suggest otherwise? If I have misrepresented Fr Lawrence’s views, I’m more than happy to correct my error.

Which model of damnation do you think Jesus taught?

LikeLike

Maximus,

The kind of scriptural exegesis that takes the stark dichotomies of prophetic Old Testament language and apocalyptic in the New Testament as demonstrative of self-evidence fails to take into account either the relativization of Old Testament anticipations in the light of New Testament fulfillment or, in the case of Revelation, the nature and limitations of genre. One still has to make discerning judgements that do not simply erase ambiguities and equivocities. And in my opinion, all scriptural exegesis also invokes some form of metaphysics. The question is, which metaphysics is truly consistent with the revelation of the gospel? Hart, myself, and Father Kimel have tried to make the case that the universalist understanding of the gospel most coherently follows from the metaphysics intrinsic to revelation. As Tom Talbott points out above, Father Lawrence implicitly presupposes certain views of will and being. He reads the scriptures through that prism and thinks he is simply reading what is there. And you, of course, will see all this as evasive of the “plain meaning.” And I will counter that a literalist and univocal interpretation of scripture cannot discern the depth and mystery of Jesus Christ; the plain meaning of the gospel is the deep meaning.

LikeLiked by 2 people

“Given that God is our transcendent and perfect Good, can you imagine a genuinely informed human being freely choosing utter misery over eternal happiness with God? Can you imagine yourself doing so?”

Honestly, I think I can. Firstly, because I’ve sinned despite knowing not only that it would hurt me in the long run, but also knowing it brought me no pleasure in the short run. And secondly, because I know how proud, stubborn and self-destructive I can be.

I think you’re relying too much on the human desire for happiness. I don’t believe this is as fundamental as you seem to suppose (at least taking happiness as a mere emotion). I would argue that neither the holy nor unholy [I couldn’t think of better terms, I’m afraid] are really after happiness, but rather, the holy desire good for goodness’ sake/the love of God, while the unholy desire power/possession.

The holy surrender themselves to God, who then surrenders Himself to them; meanwhile, the unholy seek mastery over things, which then master them. I’d say we desire freedom more than happiness.

I suppose the question is whether “hell” would humble or pride its inhabitants. But if hell is understood as sin itself, it is perhaps also pride itself… I’d say it’s wrong to suppose hell would remove or loosen attachment to sin, pride and rebellion, however horrible it may be.

Concerning the interpretation of scripture, I’d just like to suggest that we shouldn’t suppose we can interpret one scripture in terms of another at all. Just as we can’t take a verse without its chapter, nor a chapter without its verses, we can’t take one part of scripture as prior (for interpretative purposes) to any other. Of course, such a course might be insightful, but it is not authoritative over any other technique/prioritising.

God bless you

LikeLike

Ignatius,

There is equivocity in the term happiness. It can mean a merely emotive state and a product of finite intentionality. This was discussed in a number of threads. I don’t have time to find it just now. No one here is naive about human perversity. I wrote a dissertation largely dealing with Dostoyevsky, who was a master at portraying the monstrous depths. But really, this does not touch the essential point. Tom is trying to get at some of this above. The main thing that Hart, for instance, has endeavored to show, is that the metaphysics of choice are constituted by an infrangible connection to the Good. The created will does not get to choose this — it is part of our “passio essendi” — what is gifted; all our subsequent acts, however depraved, remain founded on this givenness. And thus, one can argue that our perverse choices must be delusional, in some sense mad and rooted in error. One cannot radically choose against the Good when the Good is fully seen, because we simply are desire for the Good.

LikeLike

Ignatius, let me leave you this citation from Herbert McCabe for you to chew on:

I suspect that this quote will not make sense to many contemporary Christians, of whatever tradition. I know it would not have made sense to me twenty-five years ago. It requires some understanding of (1) humanity’s divinely-given orientation to the Good and (2) evil as privation.

Is McCabe (and before him much of the classical Christian tradition) minimizing or underestimating the power of evil. I don’t think so. But I think he has placed in in a context unfamiliar to most of us.

LikeLike

Then he said it: A man had two sons.

And he who hears it for the hundreth time,

It’s as if it were the first time.

That he heard it.

A man had two sons. It is beautiful in Luke. It is beautiful everywhere.

It’s not only in Luke, it’s everywhere.

It’s beautiful on earth and in heaven. It’s beautiful everywhere.

Just by thinking about it, a sob rises in your throat.

It’s the word of Jesus that has the greatest effect

On the world.

That has found the deepest resonance

In the world and in man.

In the heart of man …

A man had two sons. Of all God’s parables

This one has awakened the deepest echo.

The most ancient echo.

The freshest echo.

Believer or unbeliever.

Known or unknown.

A unique point of resonance.

The only thing the sinner has not been able to silence in his heart.

Charles Peguy on the Parable of the Prodigal in The Portal of the Mystery of Hope

I think Peguy is “hearing the Gospel” in a way those who espouse infernalist views are not. Yet one cannot prooftext this kind of “hearing” or explain in discursive terms and in an argument that will utterly compel agreement why Peguy has understood and those who think God cooperates in the damnation of his creatures do not. I have quoted a poet, because I want to emphasize that what is involved is first simply vision — a gifted intimacy with the tender mystery of the agapeic God, but coming from this cardiognosis, speech and the ability to interpret and translate the letter, to know what truly is primary and, as Father Lawrence would say, “unambiguous” and what, in fact, should be relativized. What is certain, certain, certain, is that the scriptures read without finesse, with the absolute stolid literalism of a computer, so that there is no spirit of wisdom to discern the music, is confronted with contradictions. It simply isn’t true that one side has all the clarity and the other is chasing after will-o-the-wisps predicated on ambiguity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I have changed a sentence in the article to read: “It would make no sense—a choice made for no reason or motive whatsoever.” I’m hoping that this tiny addition will clarify the point being made—namely, if someone has no motive for doing what he does, then either he is acting randomly, i.e., indeterminately, or pathologically. In either case, it would be unjust for God to punish that person or to abandon him to the consequences of his actions.

LikeLike

I have also added a link to Jonathan Kvanvig’s contribution on heaven and hell to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

LikeLike

Still pondering things. A bit garbled, but thinking out loud. Pardon the typos.

To view hell as ‘retributive’ is to view its suffering as a ‘satisfaction’ of divine justice. And to view such suffering as ‘irrevocable’ is to say such suffering can never satisfy divine justice.

The obvious question is: How does a finite creature—of finite capacities, finite understanding, finite influence, finite perspective—commit an offense (or a finite history of offenses) justly worthy of infinite suffering?

The infinitude couldn’t derive from anything inherent to creatures, for everything about creatures is finite. It could only derive from the infinitude of God as the offended party. Finite creatures—of finite understanding, finite capacities, finite perspectives, finite worth/value—justly deserve infinite suffering because the impassible (!) God they’ve refused is of infinite value. As such, God infinitely deserves our choosing rightly and any willful disobedience, even if determined by a finite mind of finite understanding, becomes deserving of infinite retribution. The infinitude of God “justly” transfers to finite creaturely choice so that the deserved retribution of the latter is said to be “justly” unsatisfiable. It must suffer irrevocable torment, and even THAT fails to satisfy justice since the suffering never accomplishes the infinitude required of it.

Consider, the Orthodox hold that God creates freely and unnecessarily. That has to figure in. And he is infinite benevolence and beatitude. That too has to figure in. God help me, but as hard as I try to make it work, I can’t give meaning to the notion of infinite retribution.

Jerry Walls is right, I think. No sense can be made of the justice of infinite retribution. The only way to make sense of an irrevocable hell, he argues, is if one supposes that creatures—fully informed, lacking no relevant knowledge of the nature of the choice or its consequences—were to freely choose hell. He claims to find such a choice meaningful, but I think he fails to appreciate what such a choice would need to involved. It would mean the infinitude of the consequence is “per se” comprehended in its infinity and knowingly chosen as an end in itself. That is, the choice could not be in any measure grounded in a motivation that even references God or other created entities negatively. It couldn’t be chosen as a means to anything—not escaping or avoid God or anything else. It would be an infinitely informed positive choice for hell as such. (Obviously, I don’t find Ignatius’ claim to find this meaningful to imagine at all convincing. There really is nothing analogous in our experience to ground the meaningfulness of such a choice.)

And in this case hell would become neither ‘retributive’ (not designed to satisfy or slate God’s thirst for justice) nor ‘remedial’ (since it’s irrevocable). Indeed, no teleology would define created being at all. There would literally be nothing one could say about the nature of such suffering, the purpose for it, the meaning of it, the reasons of it, the divine sustaining of it, the divine relation to it, the transcendental ground of it, its place relevant to God’s purposes, or the justice of it. It would be an absolutely ‘meaningless’ reality—void of logos, void of telos, void of divine benevolence as its ground and so void of ground, and so void of relation. A finite point of pure privation having comprehended itself infinitely and so chosen itself as its own end positively, as such, without even tacit reference to anything outside itself. I apologize for the bold font. I’m just trying to SEE it clearly for what it is.

Having come to learn of Orthodoxy chiefly through its view of God as infinite beatitude, goodness and benevolence and the transcendent presence of this beatitude and benevolence as the sustaining ground and end of all things, and having been captivated by this vision myself, on the verge of conversion now and then, I now daily shake my head in disbelief that there are any Orthodox on the planet who find it possible from within the contemplation of God’s transcendent beatitude and benevolence also to embrace the doctrine of the eternal, irrevocable suffering of any person.

Tom

LikeLike

[An infinite hell would be possible only as] “a finite point of pure privation having comprehended itself infinitely and so chosen itself as its own end positively without even tacit reference to anything outside itself.”

But of course this is impossible. To choose one’s self as infinite suffering for its own sake is to act ‘teleologically’ (with suffering self as ‘end’), and as we know, the teleology of finite creatures is grounded in God and has GOD as telos, and such a choice would amount to our reconstituting ourselves ex nihilo.

smh

LikeLike

Well put Tom.

My take on it is that most (including the Eastern Orthodox) have not thought this through very well, and instead have been inundated with popularized notions of hell, heaven, justice, love, infinite, being etc.

As to conversion, I would not look to the theologoumena of anyone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Tom. You’ve done us all a good service here. Very well articulated.

LikeLike

I confess that I really have not thought through the retributive model in great depth. I read C. S. Lewis too early (late 70s) for it to influence me. Hence it became almost self-evident to me that the retributive model could not be reconciled with the gospel of grace. Hence I am not surprised by the the move from the retributive model to the free-will model that we appear to see in the Eastern tradition in the latter half of the first millennium, even while retaining the language of punishment. The tragedy is St Augustine’s retention and elaboration of retribution unto eternity.

Speculative question: What if Augustine understood so deeply the logic of damnation that he came to see that the only way to save a populated hell and unconditional divine Love was to invent the doctrine of (double) predestination?

LikeLiked by 1 person

One more thought: the retributivist model seems to work best with annihilation. After the impenitent are duly punished, why does God not withdraw from them the gift of existence, given that they are incapable of repentance?

LikeLiked by 1 person