“A human being cannot fail to love the Christ who is revealed in him, and he cannot fail to love himself revealed in Christ” (The Bride of the Lamb, p. 459). This striking statement represents, perhaps, the most provocative claim in the eschatology of Sergius Bulgakov. Upon it rests his confident hope in apokatastasis. In one form or another, we find this claim sprinkled throughout the concluding chapters of Bride of the Lamb. To be glorified by Christ is to see him, and to see him is to love him, for in him we discover our authentic selfhood and the fulfillment of our deepest yearnings.

Yet this profound insight does not lead Bulgakov to conclude that at the parousia all will be instantaneously and magically converted to God. He knows both the Bible and the human heart too well. For some, perhaps many, the return of Christ Jesus in glory will ignite a gehennic conflagration in the depth of their souls. Imprisoned in their egoism and malice, they will hate the Son and with all their might will attempt to extinguish the love born in their hearts. And so they will burn. They will know the torment of hell, a torment of love, guilt, and self-condemnation. Guiding Bulgakov’s reflections here are the homilies of St Isaac the Syrian, which he knew in Russian translation. He refers to the following passage several times:

I say that those tormented in gehenna are struck by the scourge of love. And how bitter and cruel is this agony of love, for, feeling that they have sinned against love, they experience a torment that is greater than any other. The affliction that strikes the heart because of the sin against love is more terrible than any possible punishment. It is wrong to think that gehenna are deprived of God’s love. Love is produced by knowledge of the truth, which (everyone is in agreement about this) is given to all in general. But by its power love affects human beings in a twofold manner: It torments sinners, as even here a friend sometimes causes one to suffer, and it gladdens those who have carried out their duty. And so, in my opinion, the torment of gehenna consists in repentance. Love fills with its joys the souls of the children on high. (Quoted in Bride, p. 466)

This passage is perhaps the most quoted passage from all of St Isaac’s writings. But note the bolded sentence: the torment of gehenna is repentance generated by knowledge of the truth. This translation is unfamiliar to those restricted to the English translation of Isaac’s homilies. The Transfiguration Monastery version renders the bolded sentence differently: “Thus I say that this is the torment of Gehenna: bitter regret” (Homily 28, p. 266). There’s a world of difference between repentance and bitter regret. The older translation by A. J. Weinsinck renders the sentence differently still: “I say that the hard tortures are grief for love” (p. 136). I wrote the respected Syriac scholar Sebastian Brock and asked him his opinion about the passage. In his email response he states that the Syriac word twatha is probably best translated “remorse” and observes that in the original text it is followed by the phrase “which is from love,” which Brock interprets as that “remorse that comes from the sudden awareness of God’s love: i.e. it is the sudden realisation of how one has sinned against God’s love that produces the torment in which Gehenna/Hell consists.” This phrase, however, was dropped from the ancient Greek translation, which explains why it is missing from both the Russian and Transfiguration Monastery translations. Weinsinck, working from the Syriac, appears to have captured the meaning of the original better than the others.

Reading Isaac’s homily in the Russian translation, Bulgakov interprets the the sufferings of the damned as interior conflict, the painful struggle between their desire to be united to Christ, awakened in their hearts by the parousial manifestation, and their impotence to realize their desire because of their bondage to the dominating passion to live apart from God. “Hell is love for God,” Bulgakov writes, “though it is a love that cannot be satisfied. Hell is a suffering due to emptiness, due to the inability to contain this love of God” (p. 492). Hell is knowing what it means to be made in the image of Christ and being horrified by one’s deformity (p. 487). Hell is the suffering of receiving into oneself the judgment of God, the judgment of divine image upon failed likeness:

Judgment as separation expresses the relation between image and likeness, which can be in mutual harmony or in antinomic conjugacy. Image corresponds to the heavenly mansions in the Father’s house, to the edenic bliss of “eternal life.” Likeness, by contrast, corresponds to that excruciating division within the resurrected human being where he does not yet actually possess what is his potentially; whereas his divine proto-image is in full possession of it. He contemplates this image before himself and in himself as the inner norm of his being, whereas, by reason of his proper self-determination and God’s judgment, he cannot encompass this being in himself. He cannot possess part (and this part can be large or small) of that which is given to him and loved by him in God (cf. St Isaac the Syrian); and this failure to possess, this active emptiness at the place of fullness, is experienced as perdition and death, or rather as a perishing and a dying, as “eternal torment,” as the fire of hell. This ontological suffering is described only in symbolic images borrowed from the habitual lexicon of apocalyptics. It is clear that these images should not be interpreted literally. Their fundamental significance lies in their description of the torments of unrealized and unrealizable love, the deprivation of the bliss of love, the consciousness of the sin against love. (pp. 474-475)

There can be no easy escape from this suffering, for it is the inevitable consequence of a life lived in passionate attachment to the goods of the world. The soul now finds itself naked before fiery Love. The suffering of hell must be lived out to the end. Evil must be fully expiated; the debt to justice must be paid to the last farthing:

God’s love, it must be said, is also His justice. God’s love consumes in fire and rejects what is unworthy, while being revealed in this rejection. “For God hath concluded them all in unbelief that he might have mercy upon all. O the depth of the riches both of the wisdom and knowledge of God” (Rom 11:32-33). The one not clothed in a wedding garment is expelled from the wedding feast about which it is said: “If so be that being clothed we shall not be found naked” (2 Cor. 5.3). This nakedness, this absence of that which is given and must be present, stéresis, as the original definition of evil, is fundamental for the torments of hell. It is the fire that burns without consuming. One must reject every pusillanimous, sentimental hope that the evil committed by a human being and therefore present in him can simply be forgiven, as if ignored at the tribunal of justice. God does not tolerate sin, and its simple forgiveness is ontologically impossible. Acceptance of sin would not accord with God’s holiness and justice. Once committed, a sin must be lived through to the end, and the entire mercilessness of God’s justice must pierce our being when we think of what defense we will offer at Christ’s Dread Tribunal. (pp. 475-476)

This passage surprises and confuses. How can Bulgakov declare that sin cannot be absolved, given his emphatic assertion of the love and mercy of the Creator throughout the pages of his Great Trilogy? Surely he is not rescinding what he has so clearly declared. The contradiction can be resolved if we interpret the word “forgiveness” in this passage as “remission.” God cannot simply overlook our condition of sinfulness; he cannot receive the unholy into heaven. Every human being must be perfectly conformed to the divine Image and transformed in the Holy Spirit. In this sense God’s forgiveness of sin is nothing less than the regeneration of the sinner through repentance and synergistic cooperation with the Spirit. My interpretation is confirmed, I believe, by Bulgakov’s claim that the perditional suffering is redemptive in nature: “The weeping and gnashing of teeth in the outer darkness nonetheless bears witness to the life of a spirit that has come to know the entire measure of its fall and that is tormented by repentance. But, like all repentance, these torments are salvific for the spirit” (p. 499). Hell must be experienced to the end, until it has achieved its divinely-ordained purpose. “The torments of hell are a longing for God caused by the love for God. This longing is inevitably combined with the desire to leave the darkness, to overcome the alienation from God, to become oneself in conformity with one’s revealed protoimage” (p. 492).

Bulgakov describes gehenna as “universal purgatory” (vseobshee christilische), which, as Paul Gavrilyuk notes, “describes the gist of his teaching remarkably well” (“Universal Salvation in the Eschatology of Sergius Bulgakov,” p. 125). Rejecting the long-standing retributive construal of eternal punishment, Bulgakov interprets the punishment of hell as a freely accepted purgative condition:

Hell’s torments of love necessarily contain the regenerating power of the expiation of sin by the experiencing of it to the end. However, this creative experiencing is not only a passive state, in chains imposed from outside. It is also an inwardly, synergistically accepted spiritual state (and also a psychic-corporeal state). This state is appropriately perceived not as a juridical punishment but as an effect of God’s justice, which is revealed in its inner persuasiveness. And its acceptance as a just judgment corresponds to an inner movement of the spirit, to a creative determination of the life of the spirit. And in its duration (“in the ages of ages”), this life contains the possibility of a creative suffering that heals, of a movement of the spirit from within toward good in its triumphant force and persuasiveness. Therefore, it is necessary to stop thinking of hell in terms of static and inert immobility, but instead to associate it with the dynamics of life, always creative and growing. Even in hell, the nature of the spirit remains unchanging in its creative changeability. Therefore, the state of hell must be understood as an unceasing creative activity, or more precisely, self-creative activity, of the soul, although this state bears within itself a disastrous split, an alienation from its prototype. All the same, the apostle Paul defines this state as a salvation, yet as by fire, after the man’s work is burned. It is his nakedness. (p. 498)

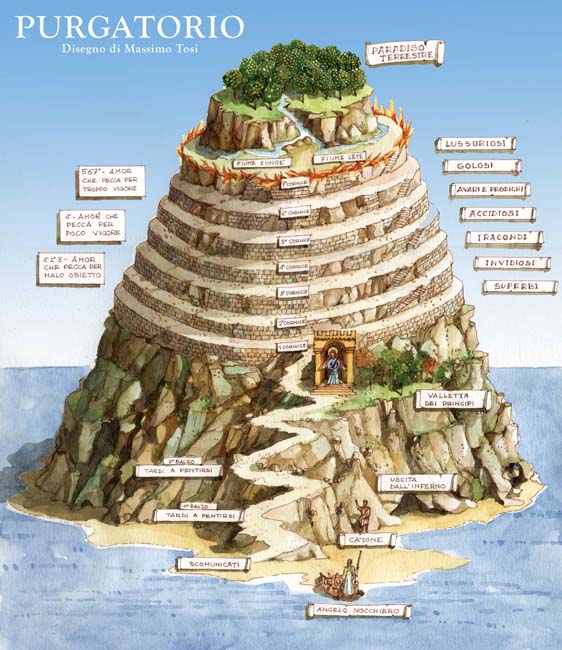

The Purgatorio of Dante Alighieri immediately comes to mind. Dante envisions purgatory as “the mountain that dis-evils those who climb” (XIII.3). Repentant souls ascend the mountain to be cleansed of their sins and made fit for the enjoyment of paradise. The punishments of each terrace are directly correlated to the vice or sin from which the soul needs to be delivered. As Anthony Esolen explains: “In purgatory man is made a ‘new creation’ by being restored to his original straightness, his original innocence before the fall of Adam” (p. xvi). It undoes the damage of sin and is thus best thought of as an infirmary rather than a prison or torture chamber.

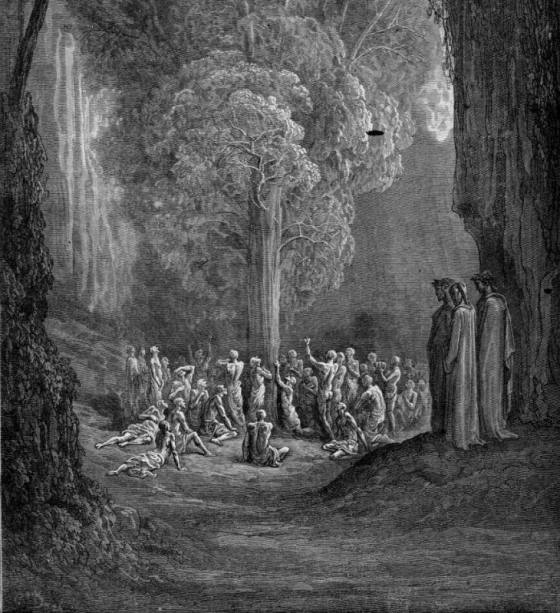

In the sixth terrace, for example, souls are cured of their gluttony by deprivation of food and drink. A large tree with “apples sweet to smell and good to eat” stands next to the path, but its branches taper downwards, thus preventing anyone from climbing the tree to reach its fruit. Dante comes across an old friend, Forese, now emaciated and gaunt, and inquires about his condition. Forese replies:

From the eternal providence divine a power descends into the tree and rain back there—a power that makes me lean and fine. And all these people singing in their pain weep for immoderate service of the threat, and thirst and hunger make them pure again. The odor of the fruit and of the spray splashing its fragrant droplets in the green kindle desire in us to eat and drink. And many a time along this turning way we find the freshening of our punishment, our punishment—our solace, I should say, For that same will now leads us to the tree as once led the glad Christ to say, “My God,” when by His opened veins He set us free. (XXIII.61-75)

The gluttons are subjected to the punishment of starvation and thirst, yet instead of raging against the punishment, they embrace it as medicine for the soul that conforms them to the sufferings of Christ. Their desire is purified and reordered to the love of God.

In an essay published in the Irish Theological Quarterly in 1922, “The Two Theories of Purgatory,” Maurice Francis Egan contrasts the two principal theories of purgatory then advanced by Roman Catholic theologians—the punishment theory and the purification theory. Proponents of both theories agree that all souls who enter into a condition of purgatorial suffering have already been pardoned of their sins and are thus destined for the beatific vision; but they disagree on the purpose of purgatorial suffering.

According to the punishment theory, the chastisements of purgatory are strictly retributive. There is a debt of justice (reatus poenae) that needs to be satisfied. Further cleansing and sanctification are unnecessary, for in death God accomplishes the regeneration of the elect. French theologian Martin Jugie succinctly states this position:

It follows from all this, that the principal—one might even say the unique—reason for the existence of Purgatory, is the temporal punishment due to sins committed after Baptism, since neither venial sin nor vicious inclination survives the first instant that follows death. Immediately on its entering Purgatory, the soul is perfectly holy, perfectly turned toward God, filled with the purest love. It has no means of bettering itself nor of progressing in virtue. That would be an impossibility after death, and it must suffer for love the just punishment which its sins have merited. (Purgatory and the Means to Avoid It, p. 5)

Those tutored in the Catholic Catechism are sometimes surprised to learn that this retributive understanding of purgatory was common among Latin theologians in the 19th and first half of the 20th century (see “Juridical Purgatory“). We find it expressed, for example, in the article on purgatory in the older Catholic Encyclopedia: “God requires satisfaction, and will punish sin, and this doctrine involves as its necessary consequence a belief that the sinner failing to do penance in this life may be punished in another world, and so not be cast off eternally from God.” When Bulgakov describes hell as “universal purgatory,” he is not thinking of this retributive view.

According to the purification theory, the chastisements of purgatory are primarily medicinal, reparative, and purgative. The theory does not deny, states Egan, that through their purgatorial suffering sinners pay the temporal debt and penalty incurred by their sins; “but it asserts that the payment is the means, the normal though not absolutely necessary means, by which God cleanses their sores and gives them the perfect spiritual health which their future life with Him requires” (p. 24). Dante’s vision of purgatory would definitely come under this category, as would also St Catherine of Genoa’s Treatise on Purgatory.

Since Vatican II the purification theory has emerged as the dominant interpretation of purgatory in the magisterial teaching of the Catholic Church. In a 1999 catechetical address Pope John Paul II describes the state of purgatory as liberation from sinful attachments:

For those who find themselves in a condition of being open to God, but still imperfectly, the journey towards full beatitude requires a purification, which the faith of the Church illustrates in the doctrine of “Purgatory.” … Every trace of attachment to evil must be eliminated, every imperfection of the soul corrected. Purification must be complete, and indeed this is precisely what is meant by the Church’s teaching on purgatory. The term does not indicate a place, but a condition of existence. Those who, after death, exist in a state of purification, are already in the love of Christ who removes from them the remnants of imperfection.

The Catholic Church authoritatively teaches that the eternal destiny of the individual is irrevocably settled at the moment of death. At this point the person has made a definitive decision for or against God. Many theologians invoke the language of “fundamental option” to describe this life-decision. Entrance into the purgatorial condition thus presupposes a “state of grace.” In his encyclical Spe Salvi Pope Benedict XVI uses the language of personal encounter to speak of the sanctifying process:

Some recent theologians are of the opinion that the fire which both burns and saves is Christ himself, the Judge and Saviour. The encounter with him is the decisive act of judgement. Before his gaze all falsehood melts away. This encounter with him, as it burns us, transforms and frees us, allowing us to become truly ourselves. All that we build during our lives can prove to be mere straw, pure bluster, and it collapses. Yet in the pain of this encounter, when the impurity and sickness of our lives become evident to us, there lies salvation. His gaze, the touch of his heart heals us through an undeniably painful transformation “as through fire”. But it is a blessed pain, in which the holy power of his love sears through us like a flame, enabling us to become totally ourselves and thus totally of God. In this way the inter-relation between justice and grace also becomes clear: the way we live our lives is not immaterial, but our defilement does not stain us for ever if we have at least continued to reach out towards Christ, towards truth and towards love. Indeed, it has already been burned away through Christ’s Passion. At the moment of judgement we experience and we absorb the overwhelming power of his love over all the evil in the world and in ourselves. The pain of love becomes our salvation and our joy. (§47; cf. the discussion of purgatory in Joseph Ratzinger, Eschatology)

The 16th century Reformers rejected purgatory and prayers for the dead as subverting the atoning sufficiency of the death of Christ and justification by faith. But in recent years some Protestant theologians and philosophers have proposed models of purgatory very similar to that of John Paul and Benedict. The best book on this subject is Purgatory: The Logic of Total Transformation by Wesleyan philosopher Jerry Walls. Walls sees purgatory as a post-mortem educational process in which justified but imperfect sinners come to a deeper understanding of their vices and sinful dispositions, thus being led by the Spirit into perfect holiness. It is unreasonable, he argues, to think that God would magically transform sinners into saints, without their free cooperation and involvement. Just as sanctification is a synergistic process in our earthly lives, so we may reasonable expect an analogous process to occur in our heavenly lives, until complete deliverance from sin is achieved.

How might we envision the educational process of purgatory? Consider Charles Dickens’s classic tale A Christmas Carol. Ebenezer Scrooge, whom the narrator describes as “hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire,” is visited on Christmas Eve by three spirits. These spirits disclose to him the truth of his life—past, present, and likely future. The spirits assist Scrooge, Walls explains, “to see others in ways he had not been able to before. By seeing himself rightly in relation to others, he comes not only to see them differently, but himself as well” (pp. 85-86). Scrooge’s encounter with reality results in his spiritual awakening and moral conversion. The narrator concludes the story: “And it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge.” Perhaps we may think of purgatory as that eschatological event in which God takes us on a review of our lives, allowing us to “see with full clarity not only how our lives have hurt others, but most importantly, how God sees them. Even more than the visits of the three spirits to Scrooge, such an extended encounter with truth through the Holy Spirit would alter us and heal our disposition to sin” (Walls, p. 85).

How might we envision the educational process of purgatory? Consider Charles Dickens’s classic tale A Christmas Carol. Ebenezer Scrooge, whom the narrator describes as “hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire,” is visited on Christmas Eve by three spirits. These spirits disclose to him the truth of his life—past, present, and likely future. The spirits assist Scrooge, Walls explains, “to see others in ways he had not been able to before. By seeing himself rightly in relation to others, he comes not only to see them differently, but himself as well” (pp. 85-86). Scrooge’s encounter with reality results in his spiritual awakening and moral conversion. The narrator concludes the story: “And it was always said of him, that he knew how to keep Christmas well, if any man alive possessed the knowledge.” Perhaps we may think of purgatory as that eschatological event in which God takes us on a review of our lives, allowing us to “see with full clarity not only how our lives have hurt others, but most importantly, how God sees them. Even more than the visits of the three spirits to Scrooge, such an extended encounter with truth through the Holy Spirit would alter us and heal our disposition to sin” (Walls, p. 85).

In disagreement with Catholic magisterial teaching, Walls is willing to entertain the possibility of post-mortem repentance. Surely the God of infinite love will go to every length to secure the eternal happiness of all human beings. “If we take this picture of God’s love as a serious truth claim,” he writes, “and not merely a piece of pious rhetoric, we have reason to accept a modified or expanded view of purgatory that grace is further extended not only to the converted who are partially transformed and imperfectly sanctified, but also to those persons who have not yet exercised any sort of saving faith” (p. 150). But the God of love will not coerce. Human beings remain free to choose eternal alienation from the Father of Jesus Christ. Yet Walls is cautiously hopeful: “The fact that we are created in God’s image is a much deeper and more resilient truth about us than our sin and whatever damage we have done to ourselves” (p. 151).

Clearly Sergius Bulgakov’s understanding of hell as universal purgatory can be helpfully supplemented by contemporary discussions of purgatorial sanctification. Those who claim that a person’s eternal destiny is definitively determined at death will, of course, disagree. But on the basis of Holy Scripture and mystical experience, Bulgakov boldly declares the salvation of all. God will never cease to summon all human beings to himself, until his universal salvific will is accomplished and sealed on the Day of Judgment.

And when all things shall be subdued unto him, then shall the Son also be subject unto him that put all things under him, that God may be all in all (1 Cor 15:28).

[24 July 2014; mildly edited]

A few questions that come to my mind as I (re)read this:

-Does Bulkagov think that anyone at all will avoid this purgation? Or is it truly “universal” – an ontological necessity that all experience to some degree?

-If Bulkagov speaks of “remission” of sins rather than “forgiveness”, where and how does “forgiveness” come into play? Does it? How does he define forgiveness? Why should people forgive if God does not? Bulkagov seems (rightly) concerned with forgiveness being construed as a legal declaration that amounts to tacit approval or “overlooking”, but there is also a sense in which forgiveness (or, perhaps, the recognition of being forgiven) is the very thing that enables repentance and new possibilities. It breaks the cycle of the torment of the “crimes against love”.

Also, I can’t help but think of George MacDonald’s Lilith….

LikeLike

Mike, regarding your first question, check the previous article on Bulgakov’s exegesis of the Lord’s parable of the Last Judgment. I think he believed that all will undergo purification, to one degree or another.

Regarding your second, I honestly do not know. My suggestion of “remission” came to me when I wrote this piece two years ago. I may be totally off-base. For me the question is, Once we understand that God is unconditional Love, what does forgiveness mean? It cannot mean that God changes his mind about us. There is a sense, I think, where we may understand forgiveness as the completion of God’s sanctifying work within us, where we are made capable of seeing and loving him. “Blessed are the pure in heart …”

LikeLike

Father,

At it’s core, it seems like Bulkagov’s thoughts here address what it means to “take sin seriously” assuming that God is love (unchangingly) within the context of the actual complexity and messy contradiction of human beings. Of course all that needs fleshing out, but I definitely don’t want to lose sight of his fundamental answer; to take sin/evil seriously is to defeat and heal it’s sting out of irrevocable love for humanity. So I suppose my focus on that issue of forgiveness and it’s role is more practical in nature.

I don’t think “remission” is off base at all given the context. George MacDonald does the same thing in “It Shall Not be Forgiven” (Unspoken Sermons), and I recall Tom Talbott doing something similar as it relates to the “unforgivable sin”. But given what’s being said here (and I realize that this is just one tiny part of Bulkagov’s thought), isn’t everysin an ‘unforgiveable’ one? So what role is there for forgiveness – then or now?

There are particular views of the cross (Penal Substitutionary Atonement) that, I think, do away with the idea of forgiveness all together. There is no forgiveness, only payment. And there is simply is no coherent substance to ‘forgiveness’ if it’s only procured after the debt that needs forgiveness has been ‘paid’. That entire line of thinking filters all terminology through an economic/judicial lens, whereas Bulkagov (and MacDonald) view things ontologically. So there is a fundamental difference.

But I’m left wondering if the following statement would hold up in this context: “There is no forgiveness, only remission.”

I don’t think the terms (forgiveness and remission) are synonymous. Take these two statements, what they suggest about forgiveness, and the practical implications for the ways that we Christians walk the world and try live to the gospel:

(1) To forgive is to enable, ignore, and tolerate evil and prevents repentance.

(2) To forgive is to disable, confront, and defeat evil and inspires repentance.

I typed those rather quickly and don’t doubt that the dichotomy could be torn to shreds. But like you said, it does get back to what we even mean by “forgiveness” if it isn’t a changing of God’s mind about us OR a forensic term without any sort of an ontological grounding, etc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Father, an Orthodox understanding of what forgiveness as “remission of sins” means similar to your conviction expressed in this comment is evident in Alexandre Kalomiros’ work, Nostalgia for Paradise. In his chapter, “Thy Sins Are Remitted” (p. 121), he opens:

Remission of sins and the healing of the soul are one and the same thing. Our repentance of sins is also our remission. Repentance means the change of our heart and mind, and our coming close to God, instead of living far from Him. Remission of sins is the overturning of the consequences of having been far from our Father’s House. In other words, it is our return to His House and His embrace, and to living once again as His children. Our departure from Him was our illness and death, and our return to Him is our cure and our eternal life.

It seems to me this is the Orthodox understanding of the nature of forgiveness. It is not essentially a legal pronouncement, neither is it a change in God or His disposition toward sinners; rather, it is a change (healing) in us effected by the Cross. Through our union with Christ, our sin goes into remission. It seems to me the Orthodox understanding consistently reflects an ontological disease model of the nature of sin and its healing (including “forgiveness”). Even where Orthodox and biblical Tradition may employ the Bible’s more forensic language, the underlying reality being referenced is this ontological actuality.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Karen. I’m glad to know that my tentative suggestion of “remission” isn’t totally off-base. I must have picked up the idea somewhere. I have not read Nostalgia for Paradise, but perhaps I picked it up from another Orthodox writer.

LikeLike

I vaguely recollect offering this quote another time in comments somewhere. I don’t know if it was under another post at your site or perhaps at Fr. Stephen’s (if so, likely during one of those long comments discussions with penal substitution advocates! :-/).

LikeLiked by 1 person

See what an influence you have been on me! 🙂

LikeLike

*Gulp!*😳

LikeLike

If forgiveness and remission are just two ways of saying the same thing, I guess there’s no issue. Semantically though, I don’t think that ‘forgiveness’ is synonymous with ‘remission’ (which then makes it the same thing as cleansing, purification, purgation, refinement, etc.) Something different is intended. And I’ve had a hard time making that intelligible in the context of forgiveness not being God changing his mind and liking me a little bit more in one moment in time vs. another.

In any case, Bulkagov (even within his thoroughly ontological framework) doesn’t treat the two terms as synonymous. If he did, it’d make no sense for him to say God does not tolerate sin, and its simple forgiveness is ontologically impossible. Substituting ‘remission’ for ‘forgiveness’ makes it unintelligible.

And that left me wondering what to do…what to do in my life and relationships if forgiveness is conceived of as something that sort of inhibits the process of ‘purgation’. From a purely human standpoint, I hope grace is more than just “allowing people to experience the results of their sins so they can learn from them.” That generally doesn’t lead to ‘keeping no record of wrongs’.

Forgiveness, in my mind, is fundamentally restorative and relational and, among other things, has to do with not holding one’s feet to the fire until the bitter end – even when all signs of sin haven’t been completely purged. And even if it’s not really a moment to moment change in God, it might seem like one for us.

LikeLike

I’m not happy with “remission” either and will probably eliminate it from the article once the thread is closed (which happens automatically after 30 days). My problem is that I’ve been away from the text for two years. I know what *I* mean by divine forgiveness, but I don’t want to import that into Bulgakov.

LikeLike