After his harrowing battle with the Un-man and his rebirth in the bowels of Perelandra, Elwin Ransom finds his way to a hidden “valley pure rose-red, with ten or twelve of the glowing peaks about it, and in the centre a pool, married in pure unrippled clearness to the gold of the sky.” He is greeted by two eldila. Together they await the arrival of the king and queen of Perelandra, Tor and Tinidril. With Tinidril he was already acquainted, but this was the first he had met Tor. The king shares with Ransom some of what he has learned. He speaks of that day when evil will be conquered on Earth, wiping out the false start that was the Fall of humanity “in order that the world may then begin.” And when his and Tinidril’s children, and their children and great-grandchildren, have “ripened and ripeness has spread from them to all the Low Worlds, it will be whispered that the morning is at hand.” Tor’s prophecy, however, creates doubts in Ransom’s mind. It seems to imply that despite the Incarnation humanity has been displaced and no longer enjoys significance in the divine plan:

I am full of doubts and ignorance. In our world those who know Maleldil at all believe that His coming down to us and being a man is the central happening of all that happens. If you take that from me, Father, whither will you lead me? Surely not to the enemy’s talk which thrusts my world and my race into a remote corner and gives me a universe, with no centre at all … To what is all driving? What is the morning you speak of? What is it the beginning of?

To this last question Tor answers: “The beginning of the Great Game, of the Great Dance.” He asks the eldila to provide further illumination. They respond with a magnificent hymn of praise (please click on the hyperlink and read the entire hymn). Note especially these strophes:

The Great Dance does not wait to be perfect until the peoples of the Low Worlds are gathered into it. We speak not of when it will begin. It has begun from before always. There was no time when we did not rejoice before His face as now. The dance which we dance is at the centre and for the dance all things were made.

Where Maleldil is, there is the centre. He is in every place. Not some of Him in one place and some in another, but in each place the whole Maleldil, even in the smallness beyond thought. There is no way out of the centre save into the Bent Will which casts itself into the Nowhere.

In the plan of the Great Dance plans without number interlock, and each movement becomes in its season the breaking into flower of the whole design to which all else had been directed. Thus each is equally at the centre and none are there by being equals, but some by giving place and some by receiving it, the small things by their smallness and the great by their greatness, and all the patterns linked and looped together by the unions of a kneeling with a sceptred love.

All that is made seems planless to the darkened mind, because there are more plans than it looked for. In these seas there are islands where the hairs of the turf are so fine and so closely woven together that unless a man looked long at them he would see neither hairs not weaving at all, but only the same and the flat. So with the Great Dance. Set your eyes on one movement and it will lead you through all patterns and it will seem to you the master movement. But the seeming will be true. Let no mouth open to gainsay it. There seems no plan because it is all plan: there seems no centre because it is all centre.

All indwell the center for God is the center, and the center indwells both the all and the particular. St Bonaventure, quoting Alain de Lille, memorably stated: “God is an intelligible sphere whose center is everywhere and whose circumference is nowhere.” The Great Dance circles around God and within God, dance within dance, movement within movement.

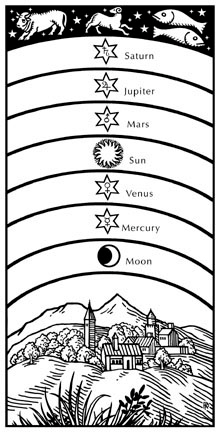

In his book The Discarded Image Lewis surveys the place of the Great Dance within medieval imagination. Intelligences and hierarchies; angels, archangels, cherubim and seraphim; the seven planets in their spheres; beasts and human beings: “everything has its place, its home, the region that suits it, and, if not forceably restrained, moves thither by a sort of homing instinct” (p. 92). Lewis invites us to gaze upon the sky on a starry night and attempt to envision it as the medievals did: “The Earth is really the centre, really the lowest place; movement to it from whatever direction is downward movement” (p. 98). Up and down are absolute. The medieval universe, “while unimaginably large, was unambiguously finite. … And because the medieval universe is finite, it has a shape, the perfect spherical shape, containing within itself an ordered variety” (p. 99). Whereas the modern eye sees the night sky as “a sea that fades away into mist,” the medieval sees it as a great building, each being given its divinely ordered place and purpose. The Earth is at the center but small when compared to the heavenly bodies and their concentric spheres. The largest sphere, enveloping all others, is the Primum Mobile. Indiscernible to the senses but posited as cosmological necessity, the first-moved and fastest sphere confers motion upon all other beings by love for the Primum Movens, the final cause of the universe. Aristotle states in his Metaphysics: “The final cause, then, produces motion as being loved, but all other things move by being moved” (12.7). God dwells with his elect beyond the Primum Mobile in the Empyrean. As Beatrice explains to Dante: “We’re on the outside of the highest body [del maggior corpo], in the purest light, in intellectual light, light filled with love, love of the true good, filled with happiness, happiness that surpasses all things sweet” (Paradiso XXX).

In his book The Discarded Image Lewis surveys the place of the Great Dance within medieval imagination. Intelligences and hierarchies; angels, archangels, cherubim and seraphim; the seven planets in their spheres; beasts and human beings: “everything has its place, its home, the region that suits it, and, if not forceably restrained, moves thither by a sort of homing instinct” (p. 92). Lewis invites us to gaze upon the sky on a starry night and attempt to envision it as the medievals did: “The Earth is really the centre, really the lowest place; movement to it from whatever direction is downward movement” (p. 98). Up and down are absolute. The medieval universe, “while unimaginably large, was unambiguously finite. … And because the medieval universe is finite, it has a shape, the perfect spherical shape, containing within itself an ordered variety” (p. 99). Whereas the modern eye sees the night sky as “a sea that fades away into mist,” the medieval sees it as a great building, each being given its divinely ordered place and purpose. The Earth is at the center but small when compared to the heavenly bodies and their concentric spheres. The largest sphere, enveloping all others, is the Primum Mobile. Indiscernible to the senses but posited as cosmological necessity, the first-moved and fastest sphere confers motion upon all other beings by love for the Primum Movens, the final cause of the universe. Aristotle states in his Metaphysics: “The final cause, then, produces motion as being loved, but all other things move by being moved” (12.7). God dwells with his elect beyond the Primum Mobile in the Empyrean. As Beatrice explains to Dante: “We’re on the outside of the highest body [del maggior corpo], in the purest light, in intellectual light, light filled with love, love of the true good, filled with happiness, happiness that surpasses all things sweet” (Paradiso XXX).

Lewis invites us to gaze once again upon the night sky:

Whatever else a modern feels when he looks at the night sky, he certainly feels that he is looking out—like one looking out from the saloon entrance on to the dark Atlantic or from the lighted porch upon dark and lonely moors. But if you accepted the Medieval model you would feel like one looking in. The Earth is ‘outside the city wall’. When the sun is up he dazzles us and we cannot see inside. Darkness, our own darkness, draws the veil and we catch a glimpse of the high pomps within; the vast, lighted concavity filled with music and life. And, looking in, we do not see, like Meredith’s Lucifer, ‘the army of unalterable law’, but rather the revelry of insatiable love. We are watching the activity of creatures whose experience we can only lamely compare to that of one in the act of drinking, his thirst delighted yet not quenched. For in them the highest of faculties is always exercised without impediment on the noblest object; without satiety, since they can never completely make His perfection their own, yet never frustrated, since at every moment they approximate to Him in the fullest measure of which their nature is capable. You need not wonder that one old picture represents the Intelligence of the Primum Mobile as a girl dancing and playing with her sphere as with a ball. Then, laying aside whatever Theology or Atheology you held before, run your mind up heaven by heaven to Him who is really the centre, to your senses the circumference, of all; the quarry whom all these untiring huntsmen pursue, the candle to whom all these moths move yet are not burned. (Discarded Image, p. 119)

Oh to see, if only for the briefest moment, the night sky in its Ptolemaic harmony and beauty. The vision is compelling, but in the Latin West it appears to have enjoyed its greatest appeal among poets and philosophers than among the spiritual writers. The reason is obvious: in the ancient cosmological model “God is much less the lover than the beloved and man is a marginal creature,” whereas for Christian preachers and spiritual writers “the fall of man and the incarnation of God as man for man’s redemption is central” (p. 120). The divine Creator of the gospel is not only the Beloved who draws creation to himself in his Goodness and Beauty but is first and foremost the Lover who seeks out his lost children to restore them to himself. Yet despite this critical difference, the cosmological and theistic visions appears to have been held together by medieval Christians without felt contradiction—at least until the revolutionary theories of Copernicus changed everything.

In an illuminating essay, “For the Dance All Things Were Made,” Paul Fiddes calls our attention to Lewis’s reworking—perhaps we might even call it his Christianization—of the medieval model of the cosmos. Recall Ransom’s concern that the creation of Perelandra has effectively displaced humanity, thus implying a meaningless, centerless universe. In the Eldelic Hymn Lewis corrects this misunderstanding by asserting the indwelling of God in creation: “He dwells (all of him dwells) within the seed of the smallest flower and is not cramped: Deep Heaven is inside Him who is inside the seed and does not distend Him.” Everything exists in the center, is the center, for God is the omnipresent center. Fiddes suggests that Lewis’s view might be called panenthesm, which to me seems anachronistic. What Lewis is presenting is simply the dynamic theism of older Christianity, without taint of Enlightenment deism. Here’s the crucial passage from Fiddes:

Certainly then, Lewis’s picture of the Great Dance combines transcendence with immanence, eternity with time. But something even more extraordinary is happening here. He is merging two images—the cosmic dance and the universal indwelling of the center. Both images in Christian tradition assume that the center is unmoving, in accord with Aristotle’s definition of the Unmoved mover, assumed (though with qualification) by Plotinus. According to the traditional image of the dance, angels, planets, and other created beings circle around the still center of God, moving around a God who is unmoving in a Neoplatonic stasis. God moves all things but remains motionless as God’s self. As Lewis summarizes the medieval tradition in his book The Discarded Image, “There must in the last resort be something which, motionless itself, initiates the motion of all other things.” In a Neoplatonist universe, indebted to both Aristotle and Plato, God, or “the One” as pure Being, cannot share in the qualities of a world of becoming and change. Further, according to the image of the center that is everywhere, God can be in all time and space just because God is eternal and unmoving. As Bonaventure puts it, pure and absolute Being “comprises and enters all durations, as if existing at the same time as their centre and circumference, because it is eternal and most present”; quoting Boethius, he goes on to say “Because it is … most immutable, for that reason ‘remaining at rest [stabilis manens] it grants motion of everything else.” The images of both dance and omnipresent center have thus traditionally relied upon the conviction that the center of the dance does not move, but when Lewis brings them together here they make a different imaginative impact. The impression made on us is that the center of the dance is itself dancing. We are not just witnessing a dance around God, but the dance of God. Lewis’s version of the Great Dance is not merely an “updated form of Christian Neoplatonism,” or a medieval commonplace. It deconstructs Neoplatonism while using its images. (C. S. Lewis’s Perelandra, pp. 34-35)

I am unconvinced that Lewis is deconstructing Neoplatonism—at least not any more so than St Athanasius, the Cappadocians, St Maximus the Confessor, and St Thomas Aquinas had already done—but clearly he is creatively revising the ancient cosmological model in a way that better expresses the Christian vision of the unmoved yet always moving Creator.

Fiddes suggests the “dynamic naturalism” of Henri Bergson as a possible source of Lewis’s metaphysical vision, despite Lewis’s own strong critique of Bergson. For Lewis the universe exists in a state of evolving unfolding. This unfolding seems to be embedded in the very structure of Perelandra. Everything is movement; everything flux and novelty. The Green Lady is commanded by Maleldil not to stay the night on the fixed island. Wave by wave, she is bade to receive the innumerable and surprising goods of his divine providence (see “Riding the Waves of Providence“). Even while journeying through the subterranean depths of Perelandra, Ransom discovers a world full of life and majestic beauty. “Assuredly the inside of this world was not for man. But it was for something.” Again the Eldilic Hymn:

Never did He make two things the same; never did he utter one world twice. After earths, not better earths but beasts; after beasts, not better beasts but spirits. After a falling, not a recovery but a new creation. Out of the new creation, not a third but the mode of change itself is changed forever. Blessed be He!

Lewis rejected the “life force” of Bergson, but retained the vitalism of his evolutionary vision. As Sanford Schwartz comments: “The Adversary may preach the gospel of creative or emergent evolution, but Lewis designs his own version of creative evolution by endowing his imaginary world with a principle of dynamic change in which even the evolutionary lapses, including the spiritual catastrophe that has overtaken our own fallen planet, are transfigured into something new and more marvelous by the redeeming act of God” (“Perelandra in Its Own Time,” in C. S. Lewis’s Perelandra, p. 55).

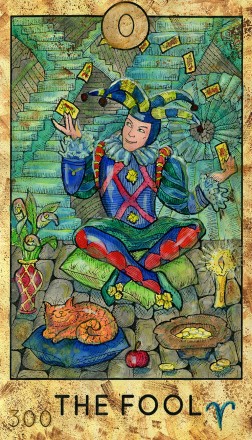

A more likely source for Lewis’s creative reworking of the medieval model is Charles Williams’s The Greater Trumps (see “The Dispassionate Sybil“). In the novel the Lee family has long guarded a set of golden figurines. The figurines are the archetypes of the forms depicted on the ancient Tarot cards. Emperor and Empress, Hierophant and High Priestess, the Hanged Man, Justice, the Devil, the Tower, the Lovers, and the Juggler circle perpetually around the seemingly stationary Fool, “reflecting the dance of the cosmos and all the movements of people and nations of the world” (Fiddes, p. 40). Henry explains the dance to Nancy:

Imagine, then, if you can, imagine that everything which exists takes part in the movement of a great dance–everything, the electrons, all growing and decaying things, all that seems alive and all that doesn’t seem alive, men and beasts, trees and stones, everything that changes, and there is nothing anywhere that does not change. That change—that’s what we know of the immortal dance; the law in the nature of things–that’s the measure of the dance, why one thing changes swiftly and another slowly, why there is seeming accident and incalculable alteration, why men hate and love and grow hungry, and cities that have stood for centuries fall in a week, why the smallest wheel and the mightiest world revolve, why blood flows and the heart beats and the brain moves, why your body is poised on your ankles and the Himalayas are rooted in the earth–quick or slow, measurable or immeasurable, there is nothing at all anywhere but the dance. Imagine it—imagine it, see it all at once and in one!

But the figure of the Fool remains a mystery. Neither Henry nor his father can explain why the Fool does not participate in the dance. Only to Sybil, purified and possessed by the divine Love, is given the revelation that the Fool moves so swiftly through the cosmic dance that he only appears immobile. “Surely that’s it,” she exclaims, “dancing with the rest; it seems as if it were always arranging itself in some place which was empty for it.” With boundless exuberance the Fool steps in and completes the measures. Williams never explicitly names the Fool as the eternal Word through whom the world was made, but the symbolic identification seems obvious to the Christian reader. But equally as fascinating is the figure of the Juggler. The Juggler dances round the edge of the circle, tossing up his little balls and catching them. When Nancy asks of Henry the import of the Juggler, he replies: “It is the beginning of all things–a show, a dexterity of balance, a flight, and a falling. It’s the only way he–whoever he was–could form the beginning and the continuation of the dance itself.” “Is it God then?” She asks. “What do we know?” he answers. “This isn’t a question of words. God or gods or no gods, these things are, and they’re meant and manifested thus. Call it God if you like, but it’s better to call it the juggler and mean neither God nor no God.” Neither God nor no God—“the Juggler,” Fiddes proposes, “is the Primum Mobile of medieval cosmology, the first moved reality moving the other spheres (balls)” (p. 41). Nancy’s subsequent vision of the Dance appears to confirm his proposal: “The dance went on in the void; only even there she saw in the centre the motionless Fool, and about him in a circle the juggler ran, for ever tossing his balls.” Yet I wonder if another interpretation might be possible. When Sybil returns to the house, having found her lost brother in the apocalyptic blizzard, the Juggler comes to her mind: “She saw–but this more in her own mind–the remote figure of the juggler, standing in the void before creation was, and flinging up the glowing balls which came into being as they left his hands, and became planets and stars, and they remained some of them poised in the air, but others fell almost at once and dropped down below and soared again, until the creating form was lost behind the flight and the maze of the worlds.” Would it be too fanciful to see here the Holy Spirit, ordering and propelling the beings made by the Word? Given his hermetic convictions, Henry could not, of course, make this identification; but Sybil certainly could. But perhaps I am working too hard to find references to the Holy Trinity.

But the figure of the Fool remains a mystery. Neither Henry nor his father can explain why the Fool does not participate in the dance. Only to Sybil, purified and possessed by the divine Love, is given the revelation that the Fool moves so swiftly through the cosmic dance that he only appears immobile. “Surely that’s it,” she exclaims, “dancing with the rest; it seems as if it were always arranging itself in some place which was empty for it.” With boundless exuberance the Fool steps in and completes the measures. Williams never explicitly names the Fool as the eternal Word through whom the world was made, but the symbolic identification seems obvious to the Christian reader. But equally as fascinating is the figure of the Juggler. The Juggler dances round the edge of the circle, tossing up his little balls and catching them. When Nancy asks of Henry the import of the Juggler, he replies: “It is the beginning of all things–a show, a dexterity of balance, a flight, and a falling. It’s the only way he–whoever he was–could form the beginning and the continuation of the dance itself.” “Is it God then?” She asks. “What do we know?” he answers. “This isn’t a question of words. God or gods or no gods, these things are, and they’re meant and manifested thus. Call it God if you like, but it’s better to call it the juggler and mean neither God nor no God.” Neither God nor no God—“the Juggler,” Fiddes proposes, “is the Primum Mobile of medieval cosmology, the first moved reality moving the other spheres (balls)” (p. 41). Nancy’s subsequent vision of the Dance appears to confirm his proposal: “The dance went on in the void; only even there she saw in the centre the motionless Fool, and about him in a circle the juggler ran, for ever tossing his balls.” Yet I wonder if another interpretation might be possible. When Sybil returns to the house, having found her lost brother in the apocalyptic blizzard, the Juggler comes to her mind: “She saw–but this more in her own mind–the remote figure of the juggler, standing in the void before creation was, and flinging up the glowing balls which came into being as they left his hands, and became planets and stars, and they remained some of them poised in the air, but others fell almost at once and dropped down below and soared again, until the creating form was lost behind the flight and the maze of the worlds.” Would it be too fanciful to see here the Holy Spirit, ordering and propelling the beings made by the Word? Given his hermetic convictions, Henry could not, of course, make this identification; but Sybil certainly could. But perhaps I am working too hard to find references to the Holy Trinity.

Lewis makes the decisive move in Mere Christianity. As understood by Christianity, he avers, divinity is inadequately described as a person. The life of the Father, Son, and Spirit is better understood as an infinite movement of self-giving and receiving:

All sorts of people are fond of repeating the Christian statement that “God is love.” But they seem not to notice that the words “God is love” have no meaning unless God contains at least two Persons. Love is something that one person has for another person. If God was a single person, then before the world was made, He was not love. Of course, what these people mean when they say that God is love is often something quite different: they really mean “Love is God.” They really mean that our feelings of love, however, and wherever they arise, and whatever results they produce, are to be treated with great respect. Perhaps they are: but that is something quite different from what Christians mean by the statement “God is love.” They believe that the living, dynamic activity of love has been going on in God for ever and has created everything else.

And that, by the way, is perhaps the important difference between Christianity and all other religions: that in Christianity God is not a static thing—not even a person–but a dynamic, pulsating activity, a life, almost a kind of drama. Almost, if you will not think me irreverent, a kind of dance. (p. 152; emphasis mine)

The Triadic God not only creates the Great Dance; he is the Great Dance and participates the Great Dance. “The dance of heaven in which the creation participates is not merely that of the ranks of angels,” writes Fiddes, “but that of the triune God” (p. 36). For the first time in the history of dogmatic reflection, a theologian of the Church explicitly identifies the inner trinitarian relations of the Godhead as the eternal Dance who grounds, generates, and sustains the Dance of the Cosmos.

Fr Aidan, I can’t thank you enough for this. I have read both Perelandra (just out of college) and The Greater Trumps (a few years ago). Perelandra came sweeping into my life transforming my view of God, sin, purpose, everything. But in the Greater Trumps the only thing I understood (at least partially) was Sybil. Now I am excited to go back and try to comprehend more in that book. The juggler possibly representing the Holy Spirit? Wow! Everything you have written here has been so delightfully illuminating for me.

“Oh to see, if only for the briefest moment, the night sky in its Ptolemaic harmony and beauty.” Yes!

Again, thank you!

LikeLiked by 4 people

A tour de force and a rich source for meditation. As with Connie I wish to go back to Perelandra and to read The Greater Trumps for the first time. Even more to learn better how to participate in the Dance.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Interesting essay, Father. Brings to the fore just how modern Lewis’ cosmos is — the medieval/Renaissance mind was no fan of mutability, as it was known. Perhaps that is because for them the cosmos that Lewis was later to appropriate was something they could believe literally and symbolically, while for Lewis and us it is believable only metaphorically. The dance is a metaphor for us (or perhaps, if you like, a hermeneutic); the music of the spheres or the great chain of being were not metaphors for the people who thought of those things. So it seems to me, the inescapable difference between the medieval and the modern mind.

LikeLiked by 2 people

This blog post and the links it provided were an answer to a prayer I hadn’t known I was praying.

You are doubtless aware that the word perichoreuō is used for dancing. It’s arguable that applying this to Patristic use of the term perichōrēsis in Trinitarian theology would be anachronistic, but the serendipity is more than suggestive.

LikeLiked by 2 people