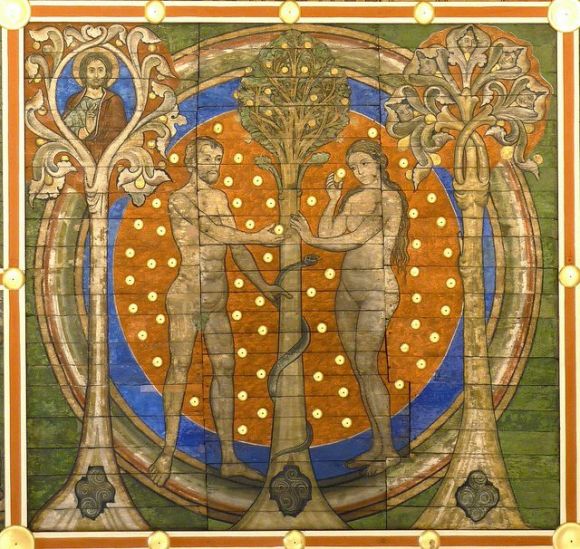

Do Orthodoxy and Catholicism significantly disagree on original sin? Both agree that by his sin and disobedience Adam broke fellowship with God and introduced into the world chaos, disharmony, corruption, evil, and death. But Orthodoxy dissents from Catholicism, we are told, on one crucial point: unlike the Catholic Church, Orthodoxy does not teach that the heirs of Adam inherit the guilt of Adam; rather they inherit mortality. Fr John Meyendorff elaborates:

Now, in Greek patristic thought, only this free, personal mind can commit sin and incur the concomitant “guilt”—a point made particularly clear by Maximus the Confessor in his distinction between “natural will” and “gnomic will.” Human nature as God’s creature always exercises its dynamic properties (which together constitute the “natural will”—a created dynamism) in accordance with the divine will, which creates it. But when the human person, or hypostasis, by rebelling against both God and nature misuses its freedom, it can distort the “natural will” and thus corrupt nature itself. It is able to do so because it possesses freedom, or “gnomic will,” which is capable of orienting man toward the good and of “imitating God” (“God alone is good by nature,” writes Maximus, “and only God’s imitator is good by his gnome“); it is also capable of sin because “our salvation depends on our will.” But sin is always a personal act and never an act of nature. Patriarch Photius even goes so far as to say, referring to Western doctrines, that the belief in a “sin of nature” is a heresy.

From these basic ideas about the personal character of sin, it is evident that the rebellion of Adam and Eve against God could be conceived only as their personal sin; there would be no place, then, in such an anthropology for the concept of inherited guilt, or for a “sin of nature,” although it admits that human nature incurs the consequences of Adam’s sin.

The Greek patristic understanding of man never denies the unity of mankind or replaces it with a radical individualism. The Pauline doctrine of the two Adams (“As in Adam all men die, so also in Christ all are brought to life” [1 Co 15:22]), as well as the Platonic concept of the ideal man, leads Gregory of Nyssa to understand Genesis 1:27—”God created man in His own image”—to refer to the creation of mankind as a whole. It is obvious, therefore, that the sin of Adam must also be related to all men, just as salvation brought by Christ is salvation for all mankind; but neither original sin nor salvation can be realized in an individual’s life without involving his personal and free responsibility.

The scriptural text, which played a decisive role in the polemics between Augustine and the Pelagians, is found in Romans 5:12 where Paul speaking of Adam writes, “As sin came into the world through one man and through sin and death, so death spreads to all men because all men have sinned [eph ho pantes hemarton].” In this passage there is a major issue of translation. The last four Greek words were translated in Latin as in quo omnes peccaverunt (“in whom [i.e., in Adam] all men have sinned”), and this translation was used in the West to justify the doctrine of guilt inherited from Adam and spread to his descendants. But such a meaning cannot be drawn from the original Greek—the text read, of course, by the Byzantines. The form eph ho—a contraction of epi with the relative pronoun ho—can be translated as “because,” a meaning accepted by most modern scholars of all confessional backgrounds. Such a translation renders Paul’s thought to mean that death, which is “the wages of sin” (Rm 6:23) for Adam, is also the punishment applied to those who, like him, sin. It presupposes a cosmic significance of the sin of Adam, but does not say that his descendants are “guilty” as he was, unless they also sin as he sinned.

A number of Byzantine authors, including Photius, understood the eph ho to mean “because” and saw nothing in the Pauline text beyond a moral similarity between Adam and other sinners, death being the normal retribution for sin. But there is also the consensus of the majority of Eastern Fathers, who interpret Romans 5:12 in close connection with 1 Corinthians 15:22—between Adam and his descendants there is a solidarity in death just as there is a solidarity in life between the risen Lord and the baptized. …

Mortality, or “corruption,” or simply death (understood in a personalized sense), has indeed been viewed since Christian antiquity as a cosmic disease, which holds humanity under its sway, both spiritually and physically, and is controlled by the one who is “the murderer from the beginning” (Jn 8:44). It is this death, which makes sin inevitable and in this sense “corrupts” nature. (Byzantine Theology, pp. 143-145)

Meyendorff reiterates this difference between East and West in his brief discussion of the Immaculate Conception. “Byzantine homiletic and hymnographical texts,” he writes, “often praise the Virgin as ‘fully prepared,’ ‘cleansed,’ and ‘sanctified.’ But these texts are to be understood in the context of the doctrine of original sin which prevailed in the East: the inheritance from Adam was mortality, not guilt, and there was never any doubt among Byzantine theologians that Mary was indeed a mortal being” (p. 147). He even goes so far as to suggest that “the Mariological piety of the Byzantines would probably have led them to accept the definition of the dogma of the Immaculate Conception of Mary as it has been defined in 1854, if only they shared the Western doctrine of original sin” (p. 148).

I distinctly remember reading these pages many years ago and wondered whether Meyendorff had accurately stated the Latin understanding of original sin. I knew that I did not understand it as a sharing in the guilt of Adam; but my knowledge of magisterial Roman Catholic teaching was limited at that time. I would not explore the matter until many years later. And the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception was beyond my Anglican sympathies. Of course Mary was a sinner—how could she not be?

Tracing the doctrine of original sin within the Latin tradition is beyond my competence. Those who are interested in the topic might want to borrow Henri Rondet’s book Original Sin. Rondet discusses at some length St Augustine’s construal of the Fall and its effects on humanity. For Augustine, he writes, “the most important consequence [of Adam’s sin] is sin itself. The children of Adam come into the world in a state of sin. To this sin of nature that they bring with them on being born, they add personal sins, so much so that of itself the human race, fallen from its primeval state, has no prospect other than hell” (pp. 120-121)—think massa damnata. In mysterious solidarity every human being shares in the sin of Adam and consequently deserves divine wrath and condemnation, even apart from their personal sins. Commenting on Ezekiel 28:4 (“Both the soul of the father is mine and the soul of the son is mine. The soul that sins is the one that will die”), the Bishop of Hippo writes:

This is why he contracted from Adam what is absolved by the grace of the sacrament: for he was not yet a a soul living separately, that is, an other soul of which it could be said, “both the soul of the father is mine and the soul of the son is mine.” Thus when he is already a man existing in himself, having become other than the one who begot him, he is not held responsible for another’s sin without his own consent. Therefore he does contract guilt [from Adam] because he was one with him and in him from whom he contracted it, when what he contracted was committed. But one does not contract it from another when each is already living his own life, of which it is said: “the soul that sins is the one that will die.” (Letter 98.1; see Phillip Cary, Outward Signs, pp.205-212, and Jesse Couenhoven, “St Augustine’s Doctrine of Original Sin“)

On the basis of this profound solidarity with Adam, Augustine concludes that infants who die without baptism are justly damned; more accurately perhaps, he infers Adamic solidarity on the basis of the salvific necessity of sacramental initiation into the body of Christ. The condition of original sin can only be cured by rebirth in the New Adam. Rondet makes clear, however, that as influential as the Augustinian construal has been, Latin theologians have not been content to simply reiterate it. Significant modifications and corrections have been made over the centuries.

So what does the Catholic Church presently teach about original sin? Fortunately for our purposes, the Catechism of the Catholic Church devotes several pages to a discussion of the creation and fall of man. It tells us that man was created in the image of God and “established in friendship with his Creator and in harmony with himself and with the creation around him” (§374). This state of friendship and harmony is called “original holiness and justice.” But man let trust die in his heart and disobeyed the command of God. He “preferred himself to God and by that very act scorned him. He chose himself over and against God, against the requirements of his creaturely status and therefore against his own good” (§398). Consequently, humanity immediately lost the grace of original holiness. The Catechism describes the consequences of this fall:

The harmony in which they had found themselves, thanks to original justice, is now destroyed: the control of the soul’s spiritual faculties over the body is shattered; the union of man and woman becomes subject to tensions, their relations henceforth marked by lust and domination. Harmony with creation is broken: visible creation has become alien and hostile to man. Because of man, creation is now subject “to its bondage to decay”. Finally, the consequence explicitly foretold for this disobedience will come true: man will “return to the ground”, for out of it he was taken. Death makes its entrance into human history. (§400)

All men are implicated in Adam’s sin, as St. Paul affirms: “By one man’s disobedience many (that is, all men) were made sinners”: “sin came into the world through one man and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all men sinned.” The Apostle contrasts the universality of sin and death with the universality of salvation in Christ. “Then as one man’s trespass led to condemnation for all men, so one man’s act of righteousness leads to acquittal and life for all men.” (§402)

So far so good. Is there anything in this presentation to which an Eastern Orthodox theologian would strongly object? One even notes the adoption by the Catechism of the Greek text for Rom 5:12: “sin came into the world through one man and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all men sinned.” But the above passage intimates mankind’s Adamic solidarity: “all men are implicated in Adam’s sin.” Perhaps here we finally arrive at the dreaded Augustinian assertion of inherited guilt. The Catechism, however, decisively qualifies such an assertion:

Following St. Paul, the Church has always taught that the overwhelming misery which oppresses men and their inclination towards evil and death cannot be understood apart from their connection with Adam’s sin and the fact that he has transmitted to us a sin with which we are all born afflicted, a sin which is the “death of the soul.” Because of this certainty of faith, the Church baptizes for the remission of sins even tiny infants who have not committed personal sin.

How did the sin of Adam become the sin of all his descendants? The whole human race is in Adam “as one body of one man”. By this “unity of the human race” all men are implicated in Adam’s sin, as all are implicated in Christ’s justice. Still, the transmission of original sin is a mystery that we cannot fully understand. But we do know by Revelation that Adam had received original holiness and justice not for himself alone, but for all human nature. By yielding to the tempter, Adam and Eve committed a personal sin, but this sin affected the human nature that they would then transmit in a fallen state. It is a sin which will be transmitted by propagation to all mankind, that is, by the transmission of a human nature deprived of original holiness and justice. And that is why original sin is called “sin” only in an analogical sense: it is a sin “contracted” and not “committed”—a state and not an act.

Although it is proper to each individual, original sin does not have the character of a personal fault in any of Adam’s descendants. It is a deprivation of original holiness and justice, but human nature has not been totally corrupted: it is wounded in the natural powers proper to it, subject to ignorance, suffering and the dominion of death, and inclined to sin—an inclination to evil that is called “concupiscence”. Baptism, by imparting the life of Christ’s grace, erases original sin and turns a man back towards God, but the consequences for nature, weakened and inclined to evil, persist in man and summon him to spiritual battle. (§§403-405; emphasis mine)

The Catechism’s presentation of original sin is open to interpretation. It does not seek to resolve the differences between the various Catholic schools. The catechetical doctrine excludes the Pelagian reduction of original sin to “the influence of Adam’s fault to bad example,” on the one hand, and the Reformation exaggeration of original sin as the radical perversion of human nature and destruction of human freedom, on the other (§406). Between these two boundaries lies the mystery of human iniquity. In the tradition of St Thomas Aquinas, the Catechism identifies the essential character of original sin as the loss of original holiness and justice: man is born into a state of spiritual death. Not only is every human being born into a world dominated by oppression, violence, and hatred; but he is also born into a condition of profound alienation from his creator. The Holy Spirit does not indwell his soul. Fallen man is thus deprived of sanctifying grace. His nature is wounded. This is the sin bequeathed to humanity by Adam. This original sin is properly understood as a condition and state, not as personal act: it “does not have the character of a personal fault.” The Catholic Church therefore agrees with Orthodox theologians that no person may be deemed morally culpable for a sin he did not personally commit. Individuals are not condemned by God because of Adam’s disobedience. In the words of Pope Pius IX: “God in His supreme goodness and clemency, by no means allows anyone to be punished with eternal punishments who does not have the guilt of voluntary fault” (Quanto conficiamur moerore [1863]). All human beings enjoy solidarity with Adam and share in the consequences of his disobedience. All are born “in Adam,” inheriting not personal guilt but corrupted human nature and separation from the divine life. In a 1986 catechetical teaching, Pope John Paul II elaborates upon the “sin” of original sin:

The Catechism’s presentation of original sin is open to interpretation. It does not seek to resolve the differences between the various Catholic schools. The catechetical doctrine excludes the Pelagian reduction of original sin to “the influence of Adam’s fault to bad example,” on the one hand, and the Reformation exaggeration of original sin as the radical perversion of human nature and destruction of human freedom, on the other (§406). Between these two boundaries lies the mystery of human iniquity. In the tradition of St Thomas Aquinas, the Catechism identifies the essential character of original sin as the loss of original holiness and justice: man is born into a state of spiritual death. Not only is every human being born into a world dominated by oppression, violence, and hatred; but he is also born into a condition of profound alienation from his creator. The Holy Spirit does not indwell his soul. Fallen man is thus deprived of sanctifying grace. His nature is wounded. This is the sin bequeathed to humanity by Adam. This original sin is properly understood as a condition and state, not as personal act: it “does not have the character of a personal fault.” The Catholic Church therefore agrees with Orthodox theologians that no person may be deemed morally culpable for a sin he did not personally commit. Individuals are not condemned by God because of Adam’s disobedience. In the words of Pope Pius IX: “God in His supreme goodness and clemency, by no means allows anyone to be punished with eternal punishments who does not have the guilt of voluntary fault” (Quanto conficiamur moerore [1863]). All human beings enjoy solidarity with Adam and share in the consequences of his disobedience. All are born “in Adam,” inheriting not personal guilt but corrupted human nature and separation from the divine life. In a 1986 catechetical teaching, Pope John Paul II elaborates upon the “sin” of original sin:

Therefore original sin is transmitted by way of natural generation. This conviction of the Church is indicated also by the practice of infant baptism, to which the [Tridentine] conciliar decree refers. Newborn infants are incapable of committing personal sin, yet in accordance with the Church’s centuries-old tradition, they are baptized shortly after birth for the remission of sin. The decree states: “They are truly baptized for the remission of sin, so that what they contracted in generation may be cleansed by regeneration” (DS 1514).

In this context it is evident that original sin in Adam’s descendants does not have the character of personal guilt. It is the privation of sanctifying grace in a nature which has been diverted from its supernatural end through the fault of the first parents. It is a “sin of nature,” only analogically comparable to “personal sin.” In the state of original justice, before sin, sanctifying grace was like a supernatural “endowment” of human nature. The loss of grace is contained in the inner “logic” of sin, which is a rejection of the will of God, who bestows this gift. Sanctifying grace has ceased to constitute the supernatural enrichment of that nature which the first parents passed on to all their descendants in the state in which it existed when human generation began. Therefore man is conceived and born without sanctifying grace. It is precisely this “initial state” of man, linked to his origin, that constitutes the essence of original sin as a legacy (peccatum originale originatum, as it is usually called).

Latin theologians typically employ the terms sin, stain of sin, guilt, punishment, and penalty to describe the condition of fallen man. Following the ritual practice of the Church, they even speak of infants and small children being baptized for the “remission of their sins.” But the Catholic Church is clear that this usage is to be interpreted analogically, not literally. The driving concern here is the universality of salvation in the New Adam and the necessity of Holy Baptism. Jesus is the savior of all humanity, infants and adults. All need to be regenerated by the Holy Spirit and incorporated into the glorified human nature of the eternal Son of God; all are summoned to the waters of baptism. Apart from this new act of grace, whether ministered sacramentally or extra-sacramentally, none can be saved.

Again I ask, Is there anything in this presentation to which an Eastern Orthodox theologian would strongly object? I acknowledge that the conceptuality of sanctifying grace, as developed in the medieval West, is alien to Orthodox reflection. Scholasticism’s concern was to explicate the impact of God’s gratuitous self-communication on the human being. But the Roman Catholic Church can hardly insist that the Eastern Church must think in scholastic categories. Consider, for example, the presentation of the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception by Fr Karl Rahner:

What is the meaning of the Immaculate Conception then? The Church’s teaching that is expressed in these words, simply states that the most blessed virgin Mother of God was adorned by God with sanctifying grace from the first instant of her existence, in view of the merits of Jesus Christ her son, that is, on account of the redemption effected by her son. Consequently she never knew that state which we call original sin, and which consists precisely in the lack of grace in men caused in them by the sin of the first man at the beginning of human history. The Immaculate Conception of the blessed Virgin, therefore, consists simply in her having possessed the divine life of grace from the beginning of her existence, a life of grace that was given her (without her meriting it), by the prevenient grace of God, so that through this grace-filled beginning of her life, she might become the mother of the redeemer in the manner God had intended her to be for his own Son. For this reason she was enveloped from the beginning of her life in the redemptive and saving love of God. Such is, quite simply, the content of this doctrine which Pius IX in 1854 solemnly defined as a truth of the Catholic faith. (Mary, Mother of the Lord, pp. 43-44; cf. “The Immaculate Burning Bush” and John Manoussakis, “Mary’s Exception“)

The Immaculate Conception means that Mary possessed grace from the beginning. What does it signify, though, to say that someone has sanctifying grace? This dry technical term of theology makes it sound as though some thing were meant. Yet ultimately sanctifying grace and its possession do not signify any thing, not even merely some sublime, mysterious condition of our souls, lying beyond the world of our personal experience and only believed in a remote, theoretical way. Sanctifying grace, fundamentally, means God himself, his communications to created spirits, the gift which is God himself. Grace is light, love, receptive access of a human being’s life as a spiritual person to the infinite expenses of the Godhead. Grace means freedom, strength, a pledge of eternal life, the predominant influence of the Holy Spirit in the depths of the soul, adoptive sonship and an eternal inheritance. (p. 48)

Like us, the Virgin Mary is born into a sinful world and must engage in spiritual battle against Satan and the principalities and powers. Like us, she lives in a world filled with violence, sickness, and death. Like us, she is mortal and lives in the knowledge of her mortality. Yet she differs from us in one crucial respect: from the very first moment she came into existence in her mother’s womb, she was indwelt by the Holy Spirit and enjoyed intimate, enduring communion with God. It seems to me that Rahner’s interpretation of the Immaculate Conception is easily translated into the language of theosis. In this sense, the blessed Virgin Mother was, by the grace of God, free from sin, original and actual. Do Orthodox Christians truly desire to deny this?

In one of his homilies on the Annunciation of the Virgin, St Sophronius of Jerusalem envisions the Archangel Gabriel speaking the following words to the young maiden:

Many became saints before you. But no one was full of grace like you; no one was blessed like you; no one was sanctified like you; no one was magnified like you; no one was purified in advance like you; no one was enlightened like you; no one was illuminated like you; no one was exalted like you; no one brought God forward like you; no one became so rich in God’s gifts like you; no one received God’s grace like you; you exceed in every human excellence. (Quoted in John Manoussakis, For the Unity of All, p. 9)

If the Latin doctrine of the Immaculate Conception is reformulated in positive terms, as the assertion of Mary’s possession of the Holy Spirit from conception, does the doctrine then become acceptable to the East? And if Catholics and Orthodox can agree on the original and life-enduring purity of the Theotokos, do they not in fact essentially agree on original sin?

(3 September 2015; rev.)

In this article Augustine’s use of analogous guilt is discussed and clarified over and against the common accusation that he taught we are personally guilty for Adams Sin. http://journal.orthodoxwestblogs.com/2018/12/03/inherited-guilt-in-ss-augustine-and-cyril/

LikeLiked by 1 person

404 How did the sin of Adam become the sin of all his descendants? The whole human race is in Adam “as one body of one man”.293 By this “unity of the human race” all men are implicated in Adam’s sin, as all are implicated in Christ’s justice. Still, the transmission of original sin is a mystery that we cannot fully understand. But we do know by Revelation that Adam had received original holiness and justice not for himself alone, but for all human nature. By yielding to the tempter, Adam and Eve committed a personal sin , but this sin affected the human nature that they would then transmit in a fallen state .294 It is a sin which will be transmitted by propagation to all mankind, that is, by the transmission of a human nature deprived of original holiness and justice. And that is why original sin is called “sin” only in an analogical sense: it is a sin “contracted” and not “committed” – a state and not an act.

405 Although it is proper to each individual,295 original sin does not have the character of a personal fault in any of Adam’s descendants. – Catechism of the Catholic Church

To impute guilt where none has objectively occurred is unjust. Catholics do not worship an unjust God. All human beings, including new-born babes who have never yet committed any personal sins, have naturally inherited the stain of that original disobedience, since Adam and Eve’s very nature was irrevocably altered. Thus, as declared by the Council of Trent, the “guilt” of original sin is not a “culpa,” which is personal guilt for a sin committed, but rather a “reatus” which is more like a debt or deprivation (of sanctity and justice) including an inherited one.

The name Adam is “mankind” in Hebrew. By being organic members of humanity or Adam, “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God” (Rom 3:23). By our very nature inherited from Adam, we are prone to commit personal sins, not unlike everyone else who reaches the age of moral reason. “Death entered the world on condition all sinned” (Rom 5:12). Infants and little children suffer and die, though they haven’t committed any personal sins. God isn’t unjust, since given the chance to grow up, they would undoubtedly sin. All human beings are implicated in the sin of Adam (mankind), guilty by association, so to speak. But no personal sin of Adam other than our own warrants the imputation of guilt.

LikeLike

And if mortality is not contracted from Adam/Eve’s sinful choice (because decay and mortality as such precede the arrival of human beings – per evolutionary history), what then? Do we push the deed back to a primordial/supratemporal rupture within ‘being’ when there were no human beings (or anything else) to do any choosing? Isn’t that essentially just disagreeing with Paul, despite minor agreements? I struggle with this.

LikeLike

Tom, in Romans 5, Paul is talking about how death has spread to the human race. He isn’t concerned with the death of other organic life forms, such as plants and animals. His message is that God intended Adam and Eve to be immortal, but by losing access to the tree of life through original sin, mankind lost the opportunity to live forever. The early chapters of Genesis are full of symbolic elements, and Adam and Eve themselves could very well be allegorical characters. Anyway, the entire physical universe, so far as we can tell, is entropic, or subject to entropy. All material systems run down or break down over time. For this reason we develop an appetite and must eat, and must sleep at night for loss of energy.

St. Thomas Aquinas recognized there was the tendency of all material things to break down over time. Aquinas’s basic answer to your question would be that because man’s body is material, it would have a natural tendency to run down and break down over time. Thus, death is natural to man. He proposed that the human body will eventually die – unless something (or someone) prevents that from happening. Nature can be supported and elevated by Divine favour, and so it is within the power of God to prevent death and our returning to dust. God chose to do this. He gave man the grace needed to avoid dying, but we lost this grace through the Fall. This is the underlying message in Genesis. Immortality isn’t something that was taken away from us but rather was denied because of sin. We forfeited God’s life-support or intervention. God could have prevented us from breaking down entirely together with the rest of the universe. But instead, man was expelled from the Garden of Eden after having fallen from God’s grace, being no longer sheltered. Paul writes, “Death entered the world on condition all sinned.”

” Now God, who is the author of man, is all-powerful, wherefore when He first made man, He conferred on him the favour of being exempt from the necessity resulting from such a matter: which favor, however, was withdrawn through the sin of our first parents.

Accordingly death is both natural on account of a condition attaching to matter, and penal on account of the loss of the divine favor preserving man from death” [Summa Theologica II-II:164:1 ad 1; cf. I:97:1].

LikeLike

While I am generally defending St. Thomas, his view that death is an intrinsic part of the material universe is difficult, both on theological and scientific grounds.

On theological grounds, St. Thomas’ view positively excludes the possibility of a material order that is disordered — no matter the level of suffering, breakdown, or dead ends that occur. His view makes it quite difficult to find an intrinsic good of order in the animal kingdom. Or rather, it makes it impossible to distinguish between the well-ordered and the ill-ordered except in human history.

On scientific grounds, we now know that St. Thomas was in a sense right to find the source of mortality in the structure of the material universe. What he did not anticipate is that the material universe itself will destroy all intelligible (material) orders, either through the big freeze or the big crunch. In either case, the liveable areas of the universe are bound to die in the dwindling light of burnt out stars on their return to the deadness of space.

The ultimate tearing apart of the fabric of the universe or the collapse into another singularity (or some other, equally dark end) is the natural end of this universe. The material universe as it is inherently lacks the order to adequately reflect divine providence. I would argue this means that natural evil must be really (and not as Aquinas has it, merely apparently) evil.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well I take it as pretty much a given fact that death proceeded humans, violence proceeded humans, pain, agony, famine, catastrophic destruction, predation, parasitism, disease, cancers and so on, stars go super-nova and black holes are formed, trapping the very light in them and kill the stars around them. For billions of years has there been destruction in the universe, which we see now as we look to the stars and so look back in time (light we see now being depending on the distance, something that happened thousands, to millions to billions of years ago, all starlight is a time capsule). The remains of our planet show that all biological life has been subject to death from it’s inception, with all the above, and our very bodies, like those of all animals alive and past, and plants and all lifeforms alive and past are formed and adapted to a universe in which death reigns, for our functions, or digestive systems, our senses and so on, have been conditioned by it. Our earlier human ancestors were just as conditioned by this, as is our mixed inheritance, both from those earlier forms, both far past (our early mammals and the reptilian ancestors that proceeded them and so on) to our recent ancestors, Australopithecus to emergence of the Homo genus, with homo habilus to the homo sapien sub-species such as the famous Neanderthal and of course modern humans (homo sapien sapien). And we are mixed because we share DNA from our Neanderthal and Devonian cousins (and possibly others which that human group coming out a Africa inter-breed with, and they with each other to an extent). We are the result of that mix, at least this is becoming ever more clear from both genetic and fossil remains (and their genetic yields).

Therefore it is seems beyond question to me, from the evidence of creation itself that death has been constant for billions of years throughout the universe, the universe has been Fallen for all that time, only our primordial instinct against this death, and the revelation, most of all in Christ and His Resurrection tells us this is truly not natural, and not what either us or creation is supposed to be. Our initiate rejection of death, our drive to eternity and paradise and utopia are not just fantasies but a deeper and truer realization of reality, both what is more fundamentally true, and what will be true (and is true in Christ).

When we turn to the Genesis account involving Adam and Eve, even in this mythic story we see a similar truth playing out. The universe is already fallen, before Adam and Eve ever listen to the serpent, there is still already a tree of the knowledge of good and evil, evil, which is the turn to nothing and non-being, already exists in creation. The serpent, as both a representation of both the animal community and of spiritual beings both, is hostile, dangerous, is full of deceit and lacks truth, and is not what is should be, it’s true and full self. Adam and Eve already exist and live in this tale in a fallen universe, but they also see Paradise around and with them, and permeating creation, they see it’s promise, the work God is bringing to a completion in and through His image and likeness, and therefore are the ones in and through whom creation is perceived more truly and clearly (and depending on the extent of that likeness, of theosis) and therefore in full in Christ, the exact image and likeness of the invisible God. In this story they see the promise of creation, and God’s purpose and the truth of it and what it will be but are also existing in the Fallen world of death that already exists.

The choice from at least one perspective then is a reflect of huamanity’s confused choice towards that fallen state as the medium of understanding and interacting with reality, both around them, of themselves and of God, who is Reality Himself. They accepted the Fall as the defining their nature and submitted to it, indicated in eating the fruit of the tree that represents this, and so dim and cut of the life seeing and towards Paradise, of the Logos present and imminent in all things, and interacting with that, which is the Tree of Life, so Paradise becomes seen only in a distance and confused, a sword of flame seeming to separate them. And they fall completely under the effects of the fallen world, and the power of death, through which they were meant (and of course ultimately still will, but through the context of their own subjection to the tyranny of death) to deliver creation.

This is I believe at least in part and indication of emergent humanity and us all, falling short of the glory of God, and submitting to idolatry as St Paul indicates in Romans, and warping both or developing natures and our perceptions and existence. And as idolatry is nothing but the turn from Being to non-being (since ultimately it is nothing, not even the supposed thing itself, since this is not seen or interacted with clearly, whether creation or any aspect of it) it binds humanity in the Fall and both diminishment of being, flourishing of being and disruption that is present and places us under that effect fully. This story tells the Fall of both humans but also the Fall as seen from a human perspective, all the more since it would always be through humans (and perhaps other embodied noetic beings, such as aliens, who knows) that God both intends to bring creation to completion (in creation as a temple, humans are the place of God’s presence and manifestation to creation, as idols were in pagan temples), and therefore in the context of the Fall salvation and redemption. Through humanity creation is and will be joined fully to the Life of God and participation in the love of the Trinity, and this I believe would always be fully in the context of the Incarnation even in a conceptual unfallen creation. The Incarnation is the heart of creation and God’s creation of all things itself, and in uniting humanity to Himself, the Son also brings in all creation (which is seen already in the Eucharist, in which the bread and wine are also the Body and Blood of Christ), and through and in which Christ is bringing all things into subjection to the Father so God will be all in all.

Since we are bound and part of creation, both in it’s earthly and celestial aspects, through this salvation connects and ripples out to all things and all things are joined in Christ, which since we are submitted and under the power of death, and are given over to it, our redemption also becomes the redemption through us of all creation with us. So as St Paul reminds us, all creation groans as with birth pangs, awaiting the revealing of the sons of God, so that in and through them, despite our own fall, it will be rescued from the futility of death, through their redemption which has also always been it;s own.

In this, I take the point in St Paul to be the shared and unified nature of humanity, which are equally connected and united into creation (to indication of Adam from the dirt but breathed into a living soul), we have a shared nature. This is so even biologically and genetically, both in life on earth having a shared ancestor, and humans come from a united and shared genetically family decent, even the cross paths interbreed, keeping that interconnected nature, as we ever become and responded to the call to be. And since we have a shared and single nature in communion, by being incarnate as one of us, from one of us, of the Virgin Mary, by grace allowed to grow as perhaps we could have done, to be the Theotokos, so is Christ united to us all, and all us to Him, and through and in us all creation is equally drawn in and united to us. And as death from Adam, which would be a shared and current nature, both from and submitted to the Fall in that turn to idolatry and to non-being and death in ignorance in misunderstanding their true good, and the true nature of reality, so that One Man, who has always been the Alpha and the Omega, the First and the Last, brings Life in place of death. And so is the sword removed from Eden and the Tree of Life opened up, and true wisdom and knowledge open, and the new and renewed nature open.

Of course these are just some preliminary thoughts as I have reflected on things, and not what more systematic thinkers can perhaps suggest, nor perhaps have I presented my thinking here all to well, but I have been thinking something down these lines of such matters so far.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In some ways, yes, I would push the deed back to a primordial rupture or even just primordial distance between God and creation, and I think Fr. Teilhard de Chardin, S.J., and Tolkein (?), if one can use the Silmarillion as a theological source, were right in wanting to reemphasize Genesis 6, and its mythological successors, over and against Genesis 3, and the symbolism of fallen powers and authorities as responsible for malformed structures in nature. Our greater understanding of the chaoskampf motif in the HB can also help explain, I think, the inherency of nonhuman evil and deformation. Simply by virtue of being created, “flesh,” Saphon (cloudy heavens) and earth are “suspended” or “hung from” nothing (Job 26). Anything vital about anything has to lent from the shaking of the Spirit (Gen. 1:2), and the Spirit “contends” with “flesh” (Gen. 6:3). Mythologically, the waters, including rain and any “living” water (flowing and capable of ritual purification), are only vital by the Spirit, becoming the “dew of lights” and the shining crystalline upper sea infused with divine tongues of fire (?), but simply are dormant on their own. I’m thinking of Theophilus of Antioch, who talks of the subtle mingling of the Spirit with the tohuvabohu waters, and the Roman baptismal rite here. By turning away from the Tree of Life and the paradisal life of the Garden, Adam and Eve turned towards “flesh” and dormancy – not the body per se but rather created weakness. Somehow, it seems to me, creation, even before Adam and Eve, by virtue of being “flesh” from the beginning (maybe we can harken to Rahab, Leviathan, Mot/Belial in Ps. 18 as symbols?), “fell out” from God, increasingly distanced itself, with some of the angels into entropy? I know this sounds like Origen, but it seems like a possible solution. But, what I cannot explain is how this “felling out” took place. I mean, Genesis 1 (unless one takes Genesis 1:1 as an absolute rather than a construct) starts us out with a picture of tohuvabohu entropy with which God interacts and infuses with his own life, but nonetheless remains distinct from. Like Ouranos or Tiamat creating monsters in abandon, Genesis seems to suggest the Spirit and Word lent the waters and the earth some freedom to propagate in a responsive and coaxing way to divine love, as co-creators, which resulted in the great sea monsters, which are not evil per se but simply “chaotic” (like the evolutionary process). But, in a narrative way, they are distinct again from the “sons of God” in Genesis 6 (so also in Ps. 82, Isaiah 14, and Ezekiel 28 – though the last two may refer to a mythological take on Adam rather than any angelic sons of God) who make a truly evil choice. Doctrinally, however, we are usually left with merging these two developments so that the fall of the angels took place outside of time. But then we risk making the “chaotic”/entropic/potentiality tohuvabohu evil in a moral sense and end up with something too close to Gnosticism. The other problem is, outside Genesis 1 itself (when one takes bereshit as as a dependent clause, which most scholars do today – although most late antique Jews and Christians, such as in the LXX, Vulgate, Josephus, Philo, and 4 Ezra, took it as an independent clause), like in Isaiah 45 and the doctrine of creatio ex nihilo (which I accept), God is made responsible for tohuvabohu so potentiality/entropic capacity is either God’s responsibility, written into the creation, or itself a kind of Origenian fall. I’d prefer to think that anything outside God has an entropic capacity which can lead to death, but without ascribing evil. I just realized that the other responses below put forward similar thoughts.

LikeLike

JGC: I would push the deed back to [1] a ‘primordial rupture’ or even just [2] ‘primordial distance between God and creation’.

Tom: Yes, these are the only two options really. But they’re very different options. ‘Primordial rupture’ is bad. It describes mortal embodiment (bodies subject to decay and death) as a postlapsarian consequence of sin. ‘Primordial distance between God and creation’, on the other hand, is a God-given good insofar as that distance just IS creation’s being – as created, as finite, as non-divine, etc. And there’s nothing evil about finitude, and so nothing threatening or bad about the ‘truth of finitude’.

JGC: …so potentiality/entropic capacity is either God’s responsibility, written into the creation, or itself a kind of Origenian fall.

JGC: Exactly. My vote is it’s God-given.

JGC: I’d prefer to think that anything outside God has an entropic capacity which can lead to death, but without ascribing evil. I just realized that the other responses below put forward similar thoughts.

Tom: Well, we don’t have any experience of an entropy that only ‘can’ but ‘does not actually’ lead to death. Decay/Death just is what we give the name ‘entropy’ to. So my own feeling is that our actual mortality, our dying, is our God-given nature from the womb of his creative word, from the get-go, i.e., our prelapsarian state. We have to begin as such because the end to which we are intended requires it, for we have to ‘make our way’, ‘take the journey’, ‘responsibly determine ourselves as finite’ as needing God, and none of that is comprehensible to me apart from our experiencing our own finitude, and that’s not possible outside experience mortality.

Who can ‘know’ the nothingness which is the truth of his finitude if he lives forever? How does one who knows not death give embrace the utter truth of his absolute contingency? So mortality for me is just the truth of finitude. It’s not a ‘good’ in the telic sense, as an ‘end’ we should celebrate. We are both intended by God to experience our finitude as death AND constituted as the transcendent desire for permanence (and hence our aversion to dying, our sense that it is ‘wrong’). But it’s not biologically wrong so much as it is ‘existentially’ wrong when viewed as final, as having the last word. For our transcendent desire construes us for a permanent future open to God. My point: To stand at THIS painful intersection is not a postlapsarian catastrophe. It’s the very possibility of theosis.

But nobody wants to say the biblical tradition misread our aversion to dying and falsely took it to be postlapsarian (which is a kind of refusal to embrace our finitude when you think about it).

LikeLike

CORRECTION

JGC: …so potentiality/entropic capacity is either God’s responsibility, written into the creation, or itself a kind of Origenian fall.

JGC: Exactly. My vote is it’s God-given.

——————————–

Obviously I mean Tom for the “Exactly’ response. Sorry!

Also, JGC, if the options are what you describe (God’s responsibility or a kind of Origenian fall), then Paul’s idea that a human agency – Adam – is responsible has to be regarded as mistaken. One can mythologize Paul in one’s own world and construe him however, but one can’t pretend that Paul didn’t believe in death having its entrance into the cosmos historically in and through the abuse of human agency.

LikeLike

Thought. Perhaps the best word to capture what I’m getting at would be ‘vulnerability’. It is the experience of vulnerability which I think is necessary, and certainly vulnerability per se is no evil. But what vulnerability is equal to the task of mediating the truth of so absolute a contingency and ontological poverty as are the truth of finitude ‘as such’? Only the experience of mortality, as far as I can see.

LikeLike

…as ‘is’ the truth of finitude… (and typographical errors)

LikeLike

I’ve been thinking about what you said these last few evenings, and I think it’s true. If one had to summarize the meaning of the Pentateuch as a whole, I would be tempted to put forward “fear of Yhwh,” vulnerability, in narrative form, as perhaps the most important ethical contribution and theme of the Pentateuch and maybe the Yahwism of the Sages as a whole (?), hence also Job and Proverbs. So, for Deuteronomy (I’m plagiarizing from Stephen Geller here), cosmological wisdom is beyond our reach, with God in the darkness, ensconced in the ancient “heart of heaven,” hidden, like God’s form, whereas the Law/Instruction alone, like the Voice, is within humanity’s reach. Our only accessible wisdom is our vulnerability, manifested in that “fear/awe.” Genesis 2-3 deals with overreaching the boundaries of our finitude, contravening the nakedness which puts us firmly with creatures despite Adam’s naming of the animals – and that vulnerability, being with creatures on the one hand and only partly being God-like in the other (hence exercise of reason and speech). This controversy regarding of “the Fall” and its consequences partially has to do, I think, with different reading traditions about Man, Woman, and the Garden in both Jewish and multiple Christian strands. Is the Garden itself Paradise, or the mere doorway to a spiritual Paradise? Was Adam clothed in God’s garments of glory already or just an “ordinary” man? What constitutes the Image? I think some other commentator also pointed to the Tree of Life as mere figurative and Cruciform possibility, a symbol of cleaving to the divine in finitude, rather than something Adam and Eve partook of, juxtaposed with an egoistic attempt at divinity. So, Augustine, as far as I can remember his Literal Commentary on Genesis, is remarkably naturalistic, and I seem to recall he allows for some quiet death as an expression of finitude, something like the Dormition. Wasn’t it Athanasius who said sin comes from our “fear of death,” rather than natural death per se, generated by alienation from God? On the other hand, Fathers and Mothers like Anthony, Macrina, and Macarius (?) – as well as Qumran and the Dead Sea Scrolls and Enoch 1 and 2 – take very literally “all the glory of Adam,” Adam being a terrifyingly bright giant, to quote the DSS, or even to the point of denying sexual differentiation. Personally, while I understand where the more exuberant tradition comes from, my reading of Genesis tends to be less florid than the latter and more like the former. I seem to recall C.S. Lewis’ Space Trilogy did something like this, where the dying Martian simply lays down peacefully and vanishes. Scripturally, one might think of the death of Moses where he dies peacefully at full age, full of vigor, and his eyes “undimmed,” unlike the rather sad death of the blinded Isaac. I recently read an article in the current Jewish Biblical Quarterly (Vol. 48, Issue 2) that put forward the idea, quite apart from the old midrash that Moses died, literally, “by the mouth of Yhwh,” that Moses died by sight of God’s face, having finally achieved that which had been denied to him in Exodus 33. On the basis that Moses was actually given the odd imperative form of “die” (Deut. 32:50), rather than mere prediction that he would die, the authors put forward that only in Deuteronomy 34:10 Moses “knew” God “face to face,” a meaning which can range from mere physical contact to a sexual euphemism, while in the other vss. that speak of Moses’ intimacy “face to face” (Numbers 12:7-8) with God, the verb is “speaking” and not “knowing.” One could imagine, maybe, that Moses’ fatal “knowing” of God could be a commentary on Deuteronomy’s primary ethical injunction for all to “cleave” to Yhwh, which can a marital term. I seem to recall somewhere that in the Hebrew Adam was said to “divorce” Yhwh in the Garden. Fancifully, maybe it’s a kind of Adamic inclusio, between Adam and Moses, of the Pentateuch in its final form? Might we be able to get Paul off the hook by saying that the kind of vulnerability and finitude, including the “door of death,” to the resurrected/theotic life, would be un-traumatic, a death, but not the “second death”? Can one enter quietly into finitude without “striving” with the Spirit, but rather “cleaving” to God? Anyhow, just my closing thoughts on this for awhile.

LikeLiked by 1 person

JGC, thank you! Just saw this.

LikeLike

I have to admit that the immaculate conception is rather foreign to my Protestant sensibilities. Do you have any literature that can help me understand what it means?

LikeLiked by 1 person

For a Roman Catholic perspective on the IC, see John Henry Newman’s “Letter to Pusey.”

LikeLike

Thank you

LikeLike

I recommend the exposition of John Duns Scotus, a mediaeval Franciscan theologian and Doctor of the Church. What he proposed eventually ended all debate among theologians over the credibility of the immaculate conception. Pope Sixtus lV established the Feast of the Immaculate Conception on 8 December 1476 and ruled that all debate should cease. Duns Scotus argued that Mary was redeemed in the most perfect way – that is by being prevented from contracting the stain of original sin – in view of the foreseen merits of Christ. We, on the other hand, are redeemed by having the stain remitted. Our redemption is curative rather than preventive. In his Apostolic Constitution Ineffabilis Deus (8 December 1854), Pope Pius lX states that this singular privilege was granted to Mary because of her election to the divine maternity. How I see it, since original sin isn’t a committed personal sin but a condition, God could mercifully intervene without negating His justice in view of her Son’s foreseen redeeming merits which aren’t constrained by linear time.

LikeLike

Thank you very much

LikeLike

Grant, I think you might like James Arraj’s book, Mind Aflame, which is a brief survey of the thought of Emile Mersch. Philip Sherrard and Hildegard of Bingen have insight into the cosmological aspect of Christ. The basic thrust of your thoughts is the kind of generous theological vision that needs to be nurtured and made the common, living thought of the Church.

LikeLike

Thanks Brian, I’ll try and see if I can find it, finances permitting of course 🙂 , theology books tend to be expensive. And I’ll try and find more about the thoughts of all the above. Thank you again for the recommendations, and I to both feel drawn to see this larger nature to salvation and would wish to see this vision flourish in the mind and thought of the Church as part of it’s regular understanding and discourse.

LikeLike

Thank you Grant and Marian. I appreciate your thoughts. There’s too much for me to respond point for point. But there is portion from each of your responses that might help me summarize my issues:

Marian: Tom, in Romans 5, Paul is talking about how death has spread to the human race. He isn’t concerned with the death of other organic life forms, such as plants and animals. His message is that God intended Adam and Eve to be immortal, but by losing access to the tree of life through original sin, mankind lost the opportunity to live forever. The early chapters of Genesis are full of symbolic elements, and Adam and Eve themselves could very well be allegorical characters. Anyway, the entire physical universe, so far as we can tell, is entropic, or subject to entropy. All material systems run down or break down over time. For this reason we develop an appetite and must eat, and must sleep at night for loss of energy.

Tom: I’m fine with symbolic elements. But death is not symbolic. We actually (not symbolically) die. Equally, the means or mechanism by which we became subject to death cannot itself be a symbol. When you say humanity “lost the opportunity to live forever” you’re presumably not describing a mere symbol, but you mean humanity did something or experienced something that marks our having become subject to death. Even if there was no historical first pair whose names were Adam and Eve, you’re still describing some event (some actuality – a choice, a failure to perceive, what have you) by which humanity subjected itself to mortality.

The problem is connecting the two (cause and effect – i.e., the event by which humanity subjected itself to death, and the effect of our actual dying). It’s a problem because the effect (death) precedes the cause (humanity). But Paul cannot not know this, and however we tweak “Adam” and “Eve” away from “a historical first pair” to represent “humanity” as such, we still have Paul believing that humanity is the doorway through which death enters. And this is simply not possible on an evolutionary timeline. So one has to then push the ‘cause’ (or event or choice or whatever it was about creation that is the occasion for death’s entry) back to creation’s origin, locate the cause back far enough to precede the death we’re trying to explain. But at that point I think we should just say we’re disagreeing with Paul, because there is no primordial human ‘agency’ convertible with the origin of the universe – and even if we wanted to imagine some such primordial vision of ‘humanity’ as such (even in Bulgakov’s terms), I mean, what would that even mean? And how could it do the job of explaining death? An original, primordial humanity (Conscious? Volitional? Who knows?) who misrelates itself to God and falls into death; then eons later, this same humanity emerges embodied through evolution and recapitulates it own primordial fall by sinning from the get-go? Are this all nice accommodates what Paul is saying? I don’t think so.

Grant: The choice from at least one perspective then is a reflect of humanity’s confused choice towards that fallen state as the medium of understanding and interacting with reality, both around them, of themselves and of God, who is Reality Himself. They accepted the Fall as the defining their nature and submitted to it, indicated in eating the fruit of the tree that represents this, and so dim and cut of the life seeing and towards Paradise, of the Logos present and imminent in all things, and interacting with that, which is the Tree of Life, so Paradise becomes seen only in a distance and confused, a sword of flame seeming to separate them. And they fall completely under the effects of the fallen world, and the power of death, through which they were meant (and of course ultimately still will, but through the context of their own subjection to the tyranny of death) to deliver creation.

Tom: Same thing here Grant. You’re imagining a concrete reality, humanity, “falling under the effects of a fallen world.” I don’t even know what that means. If humanity “falls,” then we’re imagining an “unfallen” state in which humanity was not subject to death. OK. (Though given evolution we know there is no such state human beings ever experienced.) And they then fell “under the effects of a fallen world.” So now we have a “fallen world” subject to death but human beings live in that death-filled world and they are NOT subject to death. (If they are subject to death, then from what state and into what state do they fall?) So they misrelate to reality and join the already dying world (from which they evolved through a process of death?) in being subject to death.

I can’t imagine any of this. For Paul at least, death enters through Adam, but you seem to be imagining death preceding Adam, i.e., death present in some created context and infecting all creation EXCEPT for humanity, and humanity finally falling into death through choice. Again, ‘choice’ is not a symbol. Adam can stand in symbolically for humanity as such. Fine. But choices (responsibility, misrelation, perception, etc) are events as such. When we say humanity ‘chose’, ‘misrelated’, ‘fell’, ‘lost the opportunity’, ‘became’ – we’re talking actual events within the created order.

LikeLike

Hmm, I would not at least be saying humans were unfallen if by that you mean that emergent humans were not affected and formed by death, and by a fallen nature of reality. The evidence as I started with does not back this up, our own bodies are formed by over a billion years of evolution in a world that is part of a death-subjected universe, even our genetics and our brains are conditioned by it, including pathways of thoughts and ideas and so on. So no, humans emerging were not free of the futility of creation, but I am suggesting in part that in that call to being (to God’s let there be) in this case becoming and forming even in a fallen Cosmos the image and likeness of God, an understanding an awareness of the unnaturalness of the ‘natural’ world. The ability to begin to percieve along with an awareness of God (however we formate this conception, and it way well have been a long time through the development of humanity) the wrongness of creation, as well as the truth of what creation both should be, and what it will be.

I suggest also that at least in part the mythic story of Eden contains this very tension, on one hand in with their new and young conciousness the primordial pair percieve both promise of creation as Paradise, just as they begin to openly percieve and know God, but they also live and interact with a fallen creation (again the tree of the knowledge of good and evil already exists in the garden they percieve, as does the serpent and so on, the garden is both fallen yet they can perceive the Paradise it should be and will be). Part of this perception is the present and promise of the Tree of Life, yet they have not eaten of it, even here they are yet subject as all other things to death, the Tree of Life being Christ Himself. What I do suggest further is that that God is revealed by the first Genesis account (and more fully in John 1:1) to bring creation to fullness through and in humanity, and most expectily through and in His Son, the Logos, through the Incarnation.

As creation is Fallen, this would take the context of humanity being the focal point of redemption and restoration for creation, which is Christ the Tree of Life Himself (it should also be reflected that in part this story is all of us as much as humanity’s early experience in mythic form), and through the revelation of the sons of God. Also that this story is a mythic depiction of the Fall not just of ourselves but of creation but from a human perspective, in both how we experience it and how we live through it, and how we emerged into this state of affairs (you could also see death only being fully confirmed with humanity’s experience and knowledge of it).

I also suggest somewhat speculatively that it marks humanity’s early misunderstanding of God and creation, not likely through any singular choice, but an awareness that accepted and turned to the fallen creation they were apart of as humanity developed rather then the awareness of God and of what creation should be (indicated in the story by responding to the serpent and to turning to that Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil), to that vision for want of a better word. This would also be humanity falling short even as it developed in being called into being (as coming into being by God even in creating and calling forth grants otherness to the created and I think makes it participatory in it’s emergence and creation) of the glory of God. This again could also be understood as death reign becoming complete in terms of conscious, embodied beings being and developing in subjection to it. But again, we never entirely loss the sense of the wrongness of death, and of creation around us, even as humans keep trying to accommodate it, and this sense is fully endorsed in the Resurrection.

Now this raises a possibility we could or might have developed differently, but also perhaps not, ultimately it is a story that is illuminated to understand the Fall from a human perspective, including our understanding of it’s wrongness, though only in light of Christ do we see this fully and clearly. It also underlines that it is through humanity God will bring creation, and also it’s redemption to completion, and that were are completely linked and intertwined with the creation we are part of, our redemption is it’s, and vs versa, and all centred in the Incarnation.

It is worth considering though, in light of the article’s discussion on the Theotokos, of conceptually at least the possibility of a emergent humanity, pictured as children responding to the call better. And as with the Virgin Mary in herself, the sanctifying grace of God, that of the presence of the Holy Spirit, as Father Kimel puts it.

‘Like us, the Virgin Mary is born into a sinful world and must engage in spiritual battle against Satan and the principalities and powers. Like us, she lives in a world filled with violence, sickness, and death. Like us, she is mortal and lives in the knowledge of her mortality. Yet she differs from us in one crucial respect: from the very first moment she came into existence in her mother’s womb, she was indwelt by the Holy Spirit and enjoyed intimate, enduring communion with God. It seems to me that Rahner’s interpretation of the Immaculate Conception is easily translated into the language of theosis. In this sense, the blessed Virgin Mother was, by the grace of God, free from sin, original and actual.’

It seems at least conceivable to me to think that an a developing humanity to have more fully participated in this, which would be to more fully participate and receive the grace of Christ from their perspective yet to be, at least to increasing extents like the Theotokos actually did and does. But this is speculation, though one I see contained in the frame and lens of the story that God has illuminated to help us gain understanding. And would that have preserved humans from death, or be assumed as they waited for the Incarnation, or lived increasingly not subject to the effects of a Fallen world around them, but rather been a far stronger conduit of the Life of God in Christ to the redemption of the world, and of realizing that Paradise they perceived, of being the image and likeness of God into the world, of Christ into reality far more than now? Perhaps in ways we cannot know, I don’t no for sure, though mankind through the story is given to subject the earth, which is Christ’s purpose, which means to liberate the world to be what it is truly intended to be. And in the true Man Christ we see even prior to His Resurrection that He was not subject to the futility of creation against His will, He could walk on water, survive without food and water, creation was subject to and liberated by Him. Holy Mary is also assumed rather then subject to death, and the accounts of apostles and saints down the centuries him and revelations of that glory that God shines through humanity, St Gerasimos and the lion of Jordan, St Francis of Assisi and his brother wolf showing authority over animals (and since a wolf was found buried in the church of the town in question that might not be just a pious fable), that Christ’s redemptive life towards and through humanity towards creation could have conceptually manifested, had we responded through our awareness and evolutionary and becoming differently. So could the path have been otherwise, whether or not it might have involved complete freedom from death, any more than us until the Resurrection I do not know. The story does suggest a path deviated from, as does St Paul, and this we became and confirmed ourselves as remaining fully subject to death, and of creation being and remaining subject fully to death, and of our mind, beings and whole nature including our conscious action and awareness (even where we perceived God) subjected and conditioned fully by death. God’s redemption therefore needs to not only lift us from the death of creation we a part of, but that which warps our minds, hearts and souls, and heal our wounded and enslaved natures. As suggested the Theotokos shows an image of a possibly difference in development that never happened.

How to concieve this action and confirmed embrace of non-being, of idoltary in it’s truest sense, and of creation as is and of our full subjection under it, confirming death’s dominion rather then being to source of liberation by partipationg in more openly in the Life of Christ through the Holy Spirit, through the development of humanity is probably impossible, asside from very abstractly. They only way to get a spective on it is through the medium of story, of the mythic story that has been illumiated, where Adam and Eve represent us all in our emergence, and emergence sense of humanity responded as it developed to the reality around it. Only through that lens I suggest to we gain a context to theologically understand our condition, that we are as that earthly humanity of the fallen world, bound ourselves to it in it’s Fallen state and so fully ensalved by death and are united in a shared nature, and linked to and part of the Cosmos around us. And that therefore, by uniting to Himself in the Incarnation are we, and all creation delivered from death, a promise of this seen fully in Christ Himself, and also in His Mother, through her free fait and her holiness which is the full Presence of the Life of Her Son in her. Which might yet also be a illumiation of what might have been, and how humanity at least conceptually might have partipated in that redemptive Life.

But yes, long-winded way of say, no I don’t think humanity in it itself at any point was not subject to mortality and death, and even to story indicates this as Adam and Eve never eat of the Tree of Life, and move away from it. That also does raise a possibility that perhaps it could have been otherwise in our creative becoming, as it did in person with the Mother of God, but that is only very tentative suggestion, as she was also granted that grace for a key purpose of the Redemption and salvation of all creation.

I would say though, irrespective of most of the speculation above, that both perceiving that fallen universe they a part of, and then definitively moving into it, we inherit and are subject to death through Adam in anycase. As we through our shared nature of Adam, of being from the earth and being earthly, are part of creation and not separate from it, and our nature like creation is Fallen and subject to death and mortality, to futility and destruction and turn to non-being. Just as we are all saved together, and that salvation is not individual but communal, this is not just towards humanity but the inter-relation and communion of all things together, we are part of the creation we live in, and so our nature is fallen even as it is. And whether the story is read as depicting possibility of another direction, or whether instead, humanity here as priests to God, represent and embody the Fallen creation and it’s whole Fall from away from the participation and call to the glory of God, channelled and focused into the personal story and decision of Adam and Eve, who represent both humanity but also all creation and it’s Fall through a human perspective. It is likely both/and, as I think the story likely reflects this and much more, it remains that through Adam, and through Fallen creation which Adam, our early human nature is part and parcel of, is subject to futility and death (as the fossil record, our biology and former ancestors also very clearly shows). Could things have been somewhat different, perhaps, Christ’s earthly life, that of His Mother, and of the apostles and saints show flashes of glory of not only what will be, but also perhaps a path humanity might have had and now in Christ begins to falteringly follow again, but that is my own personal inclination. I also would tend to think that conceptualisation it outside the context of the myth itself is somewhat difficult as it’s a vast and complex response and interaction towards God and creation in humanity emergence, and therefore can I think best and right now only be approached through myth. Only through myth and story can some aspects of reality like this be known, and which can then give us context in which to understand and give deeper context to the more empirical ways of knowing (such as the yields of the sciences).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Grant. Appreciate that. So – as I understand – you’re saying:

(1) Death (i.e., mortality, entropy, decay) defined the world before humanity arrived on the scene and quite apart from any choice made by human beings. That right there is huge. [I agree, but I hope you and others realize the implications, namely: (a) Death did not enter the cosmos in and through human choice (neither Adam’s nor any “human” agency we can give the name “Adam” to), and, therefore, (b) Paul, being unaware of this timeline, wrongly reasoned from the natural God-given aversion we have to dying (our capacity for transcending death) that death must have entered creation through sinful human choices. What else could he have thought? But the essential distinction between our sin and ‘death’ qua existential enemy (the sinful despair that perverts us from our misrelation to mortality) is something I think we CAN thank Paul for.]

(2) Human beings evolve into the KIND of conscious agency capable of transcending death, i.e., capable of perceiving and meaning-making in terms that transcend death. As you say, Grant, we have a God-given aversion to death. We’re intended for eternity. Human consciousness as such is a desire for God as the transcendent – and this creates the impasse: We evolve into a consciousness that cannot accept death as having the last word.

I hope you’re OK with this 2-point summary. I’m not interested in ‘what could have been’. But I do want to ask you this: If God intends us for himself, for transcendent union with him (which I agree we are so intended/designed), and if ‘death’ naturally confronts this desire as something to be ‘overcome’ and ‘transcended’, and if ‘death’ (entropy, decay, corruption) defines the material order from the get-go (not the result of any human agency) – where, pray tell, did ‘death’ come from? How did the material order come to be subject to decay?

I know my answer. I’m interested in yours. :o)

Tom (please pardon my typos – they are my original sin)

LikeLike

My answer, or at least my current sense and groping into this mystery would be firstly to always hold first the truth of Christ and His Resurrection, and in that event to absolute and clear revelation that death is utterly and completely unnatural, it is as St Paul perceived through this clearly, the enemy of God. Not from some perspectives but all, death in any form is not God’s desire or purpose for anything, and that there is this decay, lost and tend to nothingness, enslavement to it is a horror, and that horror is starkly revealed in the Resurrection. For me, that before anything is a fundamental truth, from which to think or consider anything else, it is the last and greatest enemy, and will be destroyed by being swallowed up by Life itself.

The second key I would add is that our aversion to death and inclination towards eternity has never just been our own, it is that of all creation to which we are intentionally intertwined and a part of, in communion with even. God creates and intends all creation for Himself, and will be all in all in all things, not just us, and our redemption just as our creation is not just about us at all, it is about the whole Cosmos. I would view the Genesis text as indicating that God brings creation to completion (and as part of this, redeems it) through humanity which are called into His image and likeness through that through humanity creation is also drawn to Himself, and to participate ever more deeply into His infinite Life and Love. And with this being seen as a gloss on John 1:1 this is with humanity itself drawn, formed and redeemed through the Logos, and through the Incarnation in which all things are drawn into and summed up in Christ (and reconciled to God in Him, which again is all things).

That would be the second point, we cannot think of humanity separate from the rest of creation, our very nature and even the calling to being in the image and likeness of God is related to it and in communion with it. And since creation is fallen, we form and emerge from that fallen creation, as the role of the Incarnation (which is also the heart of God’s creation and His very eternal act of creation itself) now includes redemption as part of that, and humanity are part of parcel of that purpose and calling. Creation as a whole in it’s free calling into being fell towards non-being, our own emergence being only a part of that larger drama, all things given the freedom to be and respond to that calling in some mysterious manner fall or twisted in the creative response to the agapic call to be. In this I would suggest the deeper spiritual reality and life to much of all things in the universe, and at levels beyond our current understanding (spiritual aspects of reality, heavenly realms and such things), the spiritual life and agencies that lie behind and within and interact in all things, angelic, powers and principles and such like. Like the Music of the Ainur in Tolkien’s Silmirillion something went askew in response to God’s creative call, and turn to nothingness in attempting to be, and this would not be something seen in temporal time as such (at least in terms of current perception of reality and time) but more primordial and fundamental to being called into being as a whole. Again in that mythic story of Tolkien’s it seems to be talking place ‘before’ creation or at some border of creation from nothingness, and what is seen in time is the response or playing out of that giving of space to the other, and the response of it, into which all things, even or responses are part. This could be called the Fall of the angelic beings such as Satan if you like, though to me that is part and parcel of the wider and fuller sense of Original Sin, which is the Fall and it’s affects, we are a part of it, and through us comes the completion and therefore redemption of creation, which is of course the Incarnation of the Logos and the defeating of death and drawing of all things to and into Himself, through the human nature assumed (so creation waits for the revealing of the sons of God to be freed from it’s futility).

That at least is as far as my current thoughts go, to centre on Christ and to always frame things into the larger cosmological aspect of things, both in terms of creation and within that of salvation of all things.

So those are my thoughts and reflections on this forbidding mystery as they currently sit, for what they are worth 🙂 .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom no doubt you are familiar with Nyssa’s take on the so-called double creation. I find this the most cogent to the conundrum you are dealing with. In linear time death precedes humanity’s fall, but in non-linear time the fall occurs before death.Think of the discussion re: the pre-existence of the incarnation fallacy (McCabe, Behr, Williams, etc.).

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Robert. Oh yeah. Gregory’s take is definitely in my mind. I don’t seem to be able to make sense of it though. (Side note: Hey – Anita and I are in San Diego next week! 35th anniversary. I can’t see myself getting free from the grip of her loving plans for us long enough for you and me to visit, and requesting time off would mean a swift and certain end to me; so we’ll have to meet up later under different circumstances.)

LikeLike

Gregory’s approach requires the shedding of notions of linearity. Which is not too strange given creatio ex nihilo and non-linearity as applied to the incarnation. Of course Christ pre-exists in relation to our existence, but in terms of the divine life we strictly cannot speak of pre-existence, only of existence (“before Abraham, I am”). And if the incarnation to cure sin/death is timeless (i.e. not an episode in the life of God), then sin/death and our fall is timeless as well. So the conundrum touches not only how it is God is, but also how he creates, and also on how it is God knows. In light of this, Gregory’s approach works I think.

Surely you can wrest away an hour for a pint of SD IPA! 🙂

Happy Anniversary 35th, that’s quite an accomplishment!

LikeLike