What is at stake in the universalist/infernalist debate? Perhaps the best way to answer this is to first identify what is not at stake.

What is not at stake is the christological foundation of salvation. I wholeheartedly affirm that salvation is through and in Jesus Christ, the incarnate Son of God.

What is not at stake is the freedom of the human being. I wholeheartedly affirm that God neither violates personal integrity nor coerces anyone into faith (though this does not mean that God will not allow the pain and suffering caused by a life lived apart from Life to reach intolerable intensity).

What is not at stake is the preaching of repentance. I wholeheartedly affirm that the preacher must summon sinners to repentance of their sins, moral behavior, ascetical practices, and personal participation in the life of the Holy Spirit.

What is not at stake is the horror of hell and the outer darkness. I wholeheartedly affirm that rejection of God necessarily results in spiritual death and is thus a fate about which the preacher most assuredly needs to warn his congregation.

And I’m sure there are several more “not at stakes” that I cannot think of at the moment.

So what is at stake?—the good news of Jesus Christ!

“God is love,” the Apostle John declares (1 Jn 4:8). In the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, God the Holy Trinity has been revealed as love—absolute, infinite, unconditional, abounding, ever-bestowing love. In the wonderful words of St Isaac the Syrian:

In love did He bring the world into existence; in love does He guide it during this its temporal existence; in love is He going to bring it to that wondrous transformed state, and in love will the world be swallowed up in the great mystery of Him who has performed all things; in love will the whole course of the governance of creation be finally comprised. (Hom. II.38)

All Christians affirm that God is love, though most disagree with the implications that the universalist draws from it.

Universalists affirm that God unconditionally wills the eschatological good and well-being of every human being. They reject the Augustinian, Thomist, and Calvinist positions that God elects only a portion of humanity to eternal salvation.

Universalists affirm that God never wills our our eschatological ill-being. They reject the claim that God everlastingly punishes the wicked or abandons them to interminable torment or lacks the resources to restore every person to himself in freedom and faith.

Specifically, most Christians balk at the description of the divine love as unconditional. They insist that God has in fact stipulated multiple conditions for the fulfillment of salvation, the most commonly mentioned being the free response of faith and repentance. Thus St Basil the Great:

The grace from above does not come to the one who is not striving. But both of them, the human endeavor and the assistance descending from above through faith, must be mixed together for the perfection of virtue … Therefore, the authority of forgiveness has not been given unconditionally, but only if the repentant one is obedient and in harmony with what pertains to the care of the soul. It is written concerning these things: “If two of you agree on earth about anything they ask, it will be done for them by my Father in heaven” [Mt 18:19]. One cannot ask about which sins this refers to, as if the New Testament has not declared any difference, for it promises absolution of every sin to those who have repented worthily. He repents worthily who has adopted the intention of the one who said, “I hate and abhor unrighteousness” [Ps 119:163], and who does those things which are said in the 6th Psalm and in others concerning works, and like Zacchaios does many virtuous deeds. (Short Rules PG 31.1085)1

Patriarch Jeremias II cites this passage from Basil in his critique of the Lutheran construal of justification by faith, which he interpreted as undermining the necessity of good works. His critique is well worth reading, as are the responses by the Tübingen theologians. For the Patriarch, as for so many of the Eastern Fathers, the emphasis falls not on the sola gratia, as one finds in St Augustine of Hippo and St Bernard of Clairvaux, but on the repentance that draws to us the divine mercy: “Even if salvation is by grace, yet man himself, through whose achievements and the sweat of his brow attracts the grace of God, is also the cause.” 2 Clearly, though, this is not the whole evangelical story. I understand such statements as expressions of pastoral care, as exhortations to devote our lives wholeheartedly to a life of holiness and discipleship; but I have also seen, and have experienced within myself, the spiritual and emotional damage that can be done by the rhetoric of “worthy repentance,” “worthy communion,” and of the need to become worthy of forgiveness. One cannot but hear this language as speaking of a divine love that is conditional upon the human response: God will be merciful to us if we believe, if we repent, if we obey or at least try very hard. Despite all that Christ has done, the burden of salvation falls upon the sinner. The Orthodox emphasis on synergism only reinforces the point. The cooperative interaction of divine grace and human agency is, of course, descriptively true—God saves us within, not apart from, our personal involvement—but when it is translated into the first- and second person discourse of prescriptive preaching, it will always be heard as law; and law never generates faith and hope; it only generates works-righteousness or suicidal despair. The urgent question then becomes, How do we fulfill the stipulated conditions and how can we ever know, can we know, we have fulfilled them? Jeremias offers sound counsel to the despairing, yet the despair is precisely the consequence of the exhortation to perfection that appears to call into question the all-embracing love of the Father: “those to whom the promise of the kingdom of heaven is proclaimed must fulfill all things perfectly and legitimately, and without them it shall be denied.”3 For Jeremias, justification before God is a purely future possibility and the threat of irrevocable failure is never far away.

It’s not just a matter of achieving in our teaching a scholastic kind of harmony between divine grace and human effort but rather of understanding how authentic faith is grounded upon the unconditional promise of eternal salvation. Jeremias understands that the grace and mercy of God precedes and anticipates, yet he cannot declare the love of God as unconditional, for fear of cultivating sloth, indifference, and presumption. Not unexpectedly the Tübingen theologians found wanting Jeremias’s conditionalist construal of the gospel: “But it is necessary that the divine promise be most clear and certain, so that faith may depend upon it. For were the assurance and steadfastness of the promise shaken, then faith would collapse. And if faith is overturned, then our justification and salvation will vanish.”4 To a large extent the parties are talking past each other. Why so? I suggest the following: Patriarch Jeremias is reflecting on justification from within the existential struggles and dynamics of the ascetical life, in anticipation of the coming judgment; the Lutherans are reflecting on justification from within the existential situation of having heard the last judgment spoken to them in the gospel, “ahead of time,” as it were.5 The Lutherans understand that when God speaks his eschatological promise to us, we can no longer understand our life in Christ as a transaction: we do our part and God does his. In the right preaching of the gospel, God takes upon himself the responsibility for the fulfillment of the salvific promise. “In Christ your life is good and will be good—this I declare to you in the name of the crucified and risen Son.” From this moment on, there can only be living and doing that is grounded upon and flows from the gospel. This is saving faith—a trusting and hopeful living within the absolute love that has grasped us. Whereas the preaching of conditional promise produces either fervent effort to fulfill the soteriological conditions (hence the language of merit and reward), indifference or rejection (“I like my life of sin just as it is, thank you very much”), or despair (“this task is too much for me”), the preaching of unconditional promise generates unshakable faith and hope (“I trust you, O Lord, in all things”) or offense (How dare you violate my personhood! I get my salvation the old fashioned way—I earn it!”). Robert W. Jenson puts it this way:

“Faith” is not the label of an ideological or attitudinal state. Like “justification” the word evokes a communication-situation: the situation of finding oneself addressed with an unconditional affirmation, and having now to deal with life in these new terms. Faith is a mode of life. Where the radical question is alive all life becomes a hearing, a listening for permission to go on; faith is this listening—to the gospel.6

Note that faith does not liberate us from repentance or our need of moral and ascetical instruction (and admonition) by the Church; but the churchly exhortations are now heard differently, for they are spoken within the evangelical context of the giftedness of salvation. Can we exploit the gift for our own to sinful ends? Of course. The Apostle Paul had to address that situation in Romans 6: “Are we to continue in sin that grace may abound?” Note his response: “You have died to sin in baptism and are no longer the kind of persons who would even ask that question!” The gospel performatively creates and fulfills the condition for its regenerate reception in the Spirit. Unconditional love calls forth unconditional discipleship. Because God loves you unconditionally, because he has assumed human flesh and defeated death and Satan by his resurrection on Easter morning, because he has poured out his Spirit upon humanity; therefore, believe, repent, and be baptized into the eucharistic community of faith; therefore, go forth into the world, preach the gospel, serve the poor, and love your neighbor as your Savior loves you.

Another oft-stipulated condition of salvation is the time limit. This is the central assertion of Fr Stephen De Young’s article “Hell (Unfortunately) Yes.” At some point, typically the moment of death, repentance becomes an impossibility for the sinner. As Dumitru Staniloae puts it, the reprobate are “hardened in a negative freedom that cannot possibly be overcome.”7 At this point God has no choice but to withdraw his offer of forgiveness. God abandons the wicked to their infernal fate, or as St John of Damascus puts it, the condemned are “given over to everlasting fire.”8 The divine love is understood as truly conditional, at the practical level if not at the theological (absolute predestination creates its own problems). In traditional Western presentations the divine love gives way to divine justice. In Orthodox presentations, the divine love remains theoretically unconditional but now rendered impotent, thus emptying the the divine love of content and existential relevance. If the sinner has become constitutionally incapable of repentance, then God cannot will, or desire, his good and salvation. The Omnipotence is helpless before human freedom. God has made a rock that even he cannot lift. In both Eastern and Western construals, therefore, the gospel is necessarily presented as contingent promise: “If you repent before such-and-such a time, then you will be saved.” But how do the infernalists know that final impenitence is a possibility? They do not know. It is an inference drawn from a prior dogmatic commitment to everlasting damnation. Once we accept everlasting damnation, we will configure our understanding of human being and created freedom accordingly. The universalist dissents. No matter the depth of wickedness and obduracy the human being may achieve, his or her primordial desire for God remains. There is always an open window into the soul, however tiny, for the grace of Christ to enter and work the miracle of conversion.

Those who confess the universalist hope, whether in its weaker version (St Gregory Nazianzen, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Met Kallistos Ware) or its stronger version (St Gregory Nyssen, St Isaac the Syrian, Sergius Bulgakov, David Bentley Hart), vigorously protest against the conditionalist portrayal of deity. Their objection is not grounded on the exegesis of a particular verse or two but rather upon a profound apprehension of the God they have encountered in Jesus Christ. How someone achieves this apprehension no doubt varies from person to person. Some experience it through their reading of Scripture, others through sacrament and liturgy, others through prayer and mystical experience, others through their service to the poor, others through philosophical reflection, still others through the love bestowed upon them by their neighbors and fellow believers—or any combination of the above. But once the love of God is known in the fullness and power of its radical unconditionality, there can be no turning back. Once we know God as unconditional love, we cannot unknow it. It is now the fundamental truth of God’s self-revelation. The unconditionality of the divine love can never, therefore, be just one option among many options, or be qualified, subordinated, or dismissed in the name of dogma. It is the dogma! It can only be affirmed, if it is to be affirmed, unconditionally, absolutely, uncompromisingly, immoderately, categorically—nothing less will suffice. It is the prism through which all of reality is apprehended and experienced. Absolute and infinite love—this vision of divinity now informs the faith, hopes, and dreams of the believer. As Balthasar declares:

Love alone is credible; nothing else can be believed, and nothing else ought to be believed. This is the achievement, the “work” of faith: to recognize the absolute prius, which nothing else can surpass; to believe that there is such a thing as love, absolute love, and that there is nothing higher or greater than it; to believe against all the evidence of experience (credere contra fidem” like “sperare contra spem“), against every “rational” concept of God, which thinks of him in terms of impassibility or, at best, totally pure goodness, but not in terms of this inconceivable and senseless act of love.9

In the lapidary words of the Apostle Paul: “Christ died for the ungodly” (Rom 5:6).

Yet there is much in Scripture that seems to argue against the unconditionality of divine love, including some of the parables and teachings of Jesus. We need not rehearse these texts. I imagine that we all have wrestled with them and continue to wrestle with them. I remember posing this question to Jenson in the late 80s. His reply: “Go back and reread the Bible.” At the time I didn’t find the reply particularly helpful, but I eventually came to understand what I think he was saying: “Try looking at the Bible differently. Put on a different pair of spectacles.”

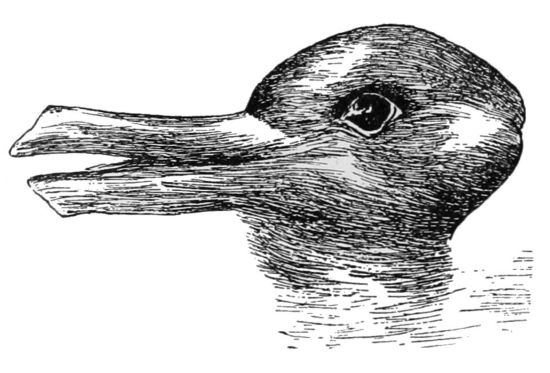

Is it a rabbit or a duck?

In his book Imagining God Garrett Green invites us to consider the role of theological paradigms in our interpretation of Scripture. Analogous to the role of paradigms within modern science, theological paradigms and metanarratives organize the data available to us and help us to make sense of it. “Our perception of parts,” he writes, “depends on our prior grasp of the whole.”10 Perhaps the greatest stumbling block to a serious consideration of the universalist reading of Scripture is our inability, or refusal, to step outside the traditional paradigm of conditional love. How is it possible that the holy God of Israel could accept us in our sinfulness, “just as we are”? How is it possible that by his Spirit, God might convert even the most wicked and pervicacious of sinners? What is needed is an imaginative leap to a new, but also very old, paradigm. Only then will we be able to apprehend the universalist reading of Scripture and Tradition as a coherent gestalt. Another way of putting it: we must read both Scripture and Tradition through a hermeneutic of Pascha.

Five years ago Fr Patrick Reardon answered the question “Dare we hope that all men be saved?” thusly: “No, we do not dare to hope for such a thing. It is a delirious fantasy, neither a proper object of Christian hope, nor a proper subject for Christian speculation.” I was a tad scandalized. I understand that Fr Patrick and other Orthodox (and Catholic) priests who have written on the topic believe that the universalist hope is heterodox; yet when I read their articles and books, I am shocked nonetheless. I hear them declaring a different, and quite depressing, gospel than the one I have long believed, confessed and preached. If God is not absolute, infinite, and unconditional love, then there is no good news of Jesus Christ to believe and proclaim, and our lives are not worth living and dying. God has been reduced to punitive divinity who commands us to achieve our righteousness, lest we be eternally damned. But if God is absolute, infinite, and unconditional love, then we may not restrict his desire, willingness, and power to accomplish his salvific ends for mankind; we may not put limits on his love, for he most certainly puts no limits on it. God wills our salvation and only wills our salvation. He never accepts our no as our final answer. In the words of the Apostle Paul: “For all the promises of God find their Yes in [Jesus Christ]. That is why we utter the Amen through him, to the glory of God” (2 Cor 1:20). And again Paul:

For I am sure that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord. (Rom 8:38-39)

What is at stake in this present debate? Nothing less than our understanding of who God has revealed himself to be in the crucified and risen Jesus Christ. Any qualification of the unconditionality of the divine love is intolerable. If there should come a point, any point, where God abandons the one lost sheep or no longer searches for the one lost coin, then God is not the Father of Jesus Christ, and our worst nightmares are true.

Apokatastasis is but the gospel of Christ’s

absolute and unconditional love

sung in an eschatological key.

(27 June 2015; rev.)

Footnotes

[1] Quoted in Augsburg and Constantinople, p. 38.

[2] Ibid., p. 42.

[3] Ibid., p. 39.

[4] Ibid., p. 126.

[5] “‘Gospel!’ is the news of God’s completely remarkable affirmation of just this rebel [i.e., sinful man], the Last Judgment let out ahead of time and revealed as, of all things, acquittal.” Robert W. Jenson, “A Dead Issue Revisited,” Lutheran Quarterly (1962): 55.

[6] Lutheranism, p. 41. On Jenson’s understanding of unconditional promise and hell, see “Hell, Freedom, and the Predestinating Gospel.”

[7] The Experience of God, VI:42.

[8] On the Orthodox Faith IV.27.

[9] Love Alone is Credible, pp. 101-102.

[10] Imagining God, p. 50.

QUOTE: “God will be merciful to us if we believe, if we repent, if we obey or at least try very hard. Despite all that Christ has done, the burden of salvation falls upon the sinner. The Orthodox emphasis on synergism only reinforces the point. The cooperative interaction of divine grace and human agency is, of course, descriptively true—God saves us within, not apart from, our personal involvement—but when it is translated into the first- and second person discourse of prescriptive preaching, it will always be heard as law; and law never generates faith and hope; it only generates legalistic works-righteousness or suicidal despair.”

Having gone through this myself – first in thirteen years of Bob Jones Southern Fried Fundamentalism, then twelve years of PCA Calvinism (the correct Calvinism, mind you!), I can only heartily agree with this last sentence. The love of God was always mentioned as a kind of sidelight to the justice that was waiting at the hands of an ever-angry God who was just waiting for Jaaaaaayzuz to return and start whuppin’ some ass on His behalf!

This legal framework produces a quiet, inner despair that crescendos every time there is a “Revival Service” with a good ole altar call. There is never any sense of assurance from constantly measuring yourself to see if you have made the cut and placated the sure wrath of God. I cannot tell you how many times I make the trek up the “sawdust trail” to once again confess my sins and ask God to save me. Along with me were many others who desperately felt their failure to meet the standard and were starting all over again by asking God to save them, only to fall into the same level of failure and despair until the next round of verbal beatings from an evangelist would send them up to the altar again to beg God for mercy.

Sick theology produces sick people.

LikeLiked by 5 people

A couple of older priests have shared with me their discouragement regarding the influx of Reformed-evangelical Christians into Orthodoxy. These new converts seem to be tone deaf to the unconditional love of God–their burning concern being the infallibility of doctrine, the need to have a closed system of tradition by which one may enjoy certainty against conflicting interpretations of Scripture. Their doctrine of infallibility is so comprehensive that by the doctrine of infallibility formulated by Vatican I pales by comparison.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As I replied to one such convert from Calvinism at his blog spot – “I’m glad you found Orthodoxy. Now I pray that Orthodoxy finds you.” Such baggage is hard to get rid of. As Fr. Joseph Huneycutt told me in an exchange of Emails: “I’ve been in the Orthodox Church 27 years and I am still learning to be Orthodox.” We converts have a lot to overcome, and the best thing we can do is to sit quietly and listen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Concerning “their doctrine of infallibility,” lot of people do seem very uncomfortable with not knowing everything. This expresses in this area about “Who will be saved? Can all be saved?” and also in other areas – I’m thinking now of those who think that if you don’t believe with certainly that God created the world in six literal days that uncertainty on your part undermines your faith in Jesus Christ, and of several other similar-ish issues.

LikeLike

This is the cataclysm of American Orthodoxy, the American reinvention of Orthodoxy in its own chiliastic, legalistic, apocalyptic, violent, cruel, fundamentalist, and deeply moronic image. Christianity rarely has much purchase in America. Inevitably, the true American religion changes everything into a parody and then into an idol.

But, for a while, Orthodoxy in America looked good. Back in the days of Meyendorff and Schmemann and the like, when Orthodoxy drew its converts mostly from high Anglicanism and Methodism and other mainstream traditions. Today, if one were to approach American Orthodoxy from outside, and from one of those saner backgrounds, one would be utterly mystified at the appeal the tradition once had. In the age of Ancient Faith Radio and so on, the American religion has simply learned how to disport itself in Orthodox garb.

We really do corrupt everything with our barbarism.

LikeLike

> In the age of Ancient Faith Radio and so on, the American religion has simply learned how to disport itself in Orthodox garb.

What particular criticisms of Ancient Faith do you have David? I’m interested to hear your thoughts on this, as AFR seems to be pretty well respected

LikeLike

Ed – we have even more in common (I now see) other than our ages: I too was raised (the son of a) Baptist (pastor) – Then (starting in college) spent about 15 years in the PCA (as a graduate of RTS and a pastor myself) – But I (like you) certainly don’t try and make my current Christian Universalist perspectives comport to Calvinism. Instead I just shake my head in disbelief that I could have ever believed many of the things I did “back when”, and (hopefully) have a little more patience with my Reformed brethren whose scales have not yet fallen when it comes to God’s Sovereign (Unconditional) Love! – Thanks!

LikeLike

Infernalism is simply an evil belief that has yet to be excised from Christianity. You still have Chrisitians who support chattel slavery, so it’s not surprising. Shocking, but not surprising.

All this energy to establish God is the source and author of evil. It beggars the imagination. But here we are.

LikeLike

If universalism is not true, then this is what the gospel must be: “Hey earthlings”, announce the angels, “Here’s some good news – not all of you will be damned forever, but a tiny and arbitrary number of elected ones will be saved. Furthermore, neither the elect nor the reprobate will know which category they are in until it’s too late anyway.” Now, go, create another world religion based in the bondage of guilt and fear.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another? What other world religion does that?

Corruptio optimi pessima.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Religion of Peace

LikeLike

Universalism changes the “if” to a “when”, as I see it, and changes the tense:

“God has been merciful to us, and through his mercy we will come to repentance, and when we repent, we will be saved.”

God’s mercy consists in procuring our repentance, not in accepting it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very well put. In this case, the term ‘repentance’ loses any negative aspect (introspective shame, guilt) and is uplifted into a two-fold song of Joy and Thanksgiving directed in praise of the infinite beauty of the goodness of God. Unconditional love, coming from the Creator of all things, is an irresistible force that honours our free will, for attraction never becomes coercion, and God is the most attractive and desirable object of human love. (This is how the Prime Mover is properly understood.)

LikeLike

I deeply hope universalism is true. Because of infernalism I deeply regret the birth of my daughter. I refused to have more children, and incurred the wrath of other churchgoers (in a church where people tend to have larger families) by saying that having children simply added more souls to eternal damnation. Looking back I’m rather surprised I wasn’t tossed out. However the choking fear that my daughter will not be saved hovers over me every day. I have no idea how parents cauterize their feelings in this area; I can only read articles such as these to lessen the fear.

However there is one verse that concerns me, that I have not seen dealt with, whether by Thomas Talbott, DBH, or others. Using Dr. Hart’s New Testament translation, 1 Peter 4:17-18 “For it is the time of judgement to commence with the house of God; and if it starts with us, what will the end be for those who are recalcitrant to God’s good tidings? For, “If the righteous man is barely saved, where will the impious and sinful man show up?”

LikeLike

Sarah, I just discovered your comment hiding in the spam queue. This rarely happens but for whatever reasons sometimes the WordPress software screws up. My apologies.

LikeLike

Sarah – you are rare among believers in that you take infernalism deeply seriously – that IF it is true then your logic is irrefutable.

But – I am personally convinced it is not true. I would point out a few things about this verse in particular:

1. The question is asked and not answered (“then what will become of the ungodly and the sinner?”) – I take the emphasis to be on the seriousness and the severity of God’s judgment – which “sound” Christian Universalism never denies. But it does NOT have anything to say about **eternal** conscious torment.

2. Somewhat ironically – whatever this passage means – it should in some sense be tempered by things stated earlier in the same epistle: we have the scriptural basis of what is called “the harrowing of hell” – which at least gives us a small glimmer into the gracious disposition that God in Christ has toward us – see especially 3:18-19 and 4:6.

3. Finally it is very interesting to realize that Peter’s quotation of this proverb almost certainly is from the Greek translation of the Old Testament (the Septuagint) – whereas the Hebrew more accurately translated says, “If the righteous receive their due on earth, how much more the ungodly and the sinner!”. What that should do in the very least is to remind us that the judgement of which Peter speaks has far more to do with earthy discipline than “eternal”.

I often am reminded of a most wonderful verse from Psalm 119:160: “The sum of thy Word is Truth”. It is not a verse here or there that will establish us in the peace that surpasses understanding. It is only as we gaze contemplatively into the “face” of Jesus that we will even begin to see the infinite depths of His eternal nature: Love.

Please know you are in our prayers as you struggle with these issues – Above all I pray along with Paul that you will “see” and know from the depths “Christ’s love that surpasses knowledge”… God loves your daughter (and you!) more than you could ever begin to imagine…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Sarah, it is truly heart-wrenching to hear the suffering and fear for yourself and your daughter that you have lived under, the terror of infernalism never produces good fruit, but rotten fruit of fear, terror of God, of depression and constant anxiety and bondage. There is no freedom or love in it, none the fruits of the Spirit and found in this doctrine.

I can’t add much to what Wayne here talks concerning the verse, I would just add it is addressed to Christians to exhort them to keep living faithfulness and love even in hard and trying situations, even if the world is mocking you or calling you naive, or worse, it is to share as it says in the Cross where Christ is mocked and hurt. It isn’t addressing non-Christians (or currently non-Christians) at all. Secondly, see how this doctrine makes you read into the text what isn’t there, nowhere does this verse announce or talk about non-Christians or unrighteous (we are all unrighteous) at a certain point (say death or Christ’s appearing) are given over to eternal torment and torture, nor even are they destroyed. It at most means a harder and tougher experience and shock will be in store (which universalism as here doesn’t deny), but nothing says eternal torment or even annihilation. It is a pretty clear point but one, and I know, I’ve been very much where you are, we just don’t see, the interpretive ‘glasses’ we are given by the tradition we are in, and even wider Western society that we grow up in, condition both assume eternal hell is part of Christianity without question, and to therefore read that into verses without question. But Scripture does not explain itself, it doesn’t stand independent of the interpretative tradition it is read through, through conditions and determines how anything in it is understood and heard.

It depends strongly also in interpreting a verse of Scripture what is prioritized, so for infernalists clear statements by St Paul are heavily qualified such as 1 Corinthians promising death will be destroyed and God will be all in all, which means death can nowhere in all creation, there cannot therefore be some eternal death going on somewhere with some lost forever, as then death is neither destroyed and is in fact triumphant in places and very much remaining, whether in eternal torment or annihilation. Or in Romans that as all in Adam die, all in Christ are made alive, or the clear statement that all shall bow and declare Christ Lord, yet telling us prior that we can only call Him Lord in truth by the Spirit and to salvation, or Christ stating that when raised on the Cross He would draw, in fact drag, all people to Him. And so and so on, but coming as we do from infernalist dominated traditions, we automatically miss the force of these, qualifying them already in our heads, because of course we are conditioned to see infernalism as unquestionable (and we wouldn’t be taking Scripture, tradition or what have you seriously and probably be weak-willed liberal/unbelievers if we did, or gas-lighting and terror tactics), and instead both privilege judgement passages that are often more ambiguous, certainly in their interpretation (as even here) and also read those judgement passages as meaning infernalism (which they don’t say, and definitely not here).

I really recommend these articles (particularly the first for getting the main point I’m driving at across) that can help:

Truly again my heart goes out to you and all this has stolen from you, the more I reflect and the more hear from people suffering under this teaching the more horrid and evil it is to me, a teaching that comes to steal and destroy, and does not give life and that abundantly, it is of the thief not the Shepard, one that takes your joy and love for God and replaces it with fear, terror and horror. Please know this isn’t Christ, and this isn’t your loving Father, thinking of how much you love your daughter, how could your Father and hers, who loves her even more greatly, intensely and devotedly then even you, bring about a reality freely under His ultimate control without anything constraining or forcing Him, in which there is even the shadow of the smallest sliver of a possibility where she could be lost forever, tormented forever. NO, that isn’t possible, God is love, and nothing can separate you or her from the love of God in Christ, not life, not death, not heaven nor hell, nor earth, no devils, angels or anything else, nothing could ever keep her or you from fully enjoying the fullness of life, joy and wonder beyond imagining He has in store for you. Be not afraid, He will never abandon you or her, or anymore, no matter how far they wonder, He will not cease until the last sheep has been found, until all is restored, and all paths will lead to Him even as He is on the journey with you, until death is destroyed and God all in all, and all tears shall be wiped away and everything made new.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much for your beautiful comment-it was very much needed tonight. I cried from relief at reading the hope in your words.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your reply. The comments and articles on this site have been a beacon of hope.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfortunately Roman Catholicism has always had this literalistic, rigid view of doctrinal authority. For a great exposition of that view, please see Justin Coyle’s explication of Denzinger Theology in his article “May Catholics endorse universalism. “, which is on this blog.

Conservative Catholics who subscribe to such views are every bit as self- righteous and obnoxious as evangelical fundamentalists. I had an extremely unpleasant experience with such an individual. She happened to be my secretary and was unfortunately quite strident in her efforts to convert others to her way of seeing things. She began proselytizing to one of my colleagues, an affable lad who was searching for both meaning and female companionship. One day at lunch, he sat down and asked me about my view of Catholicism and whether conversion might be a viable option. I shared my honest opinion: that religious conversion is a very serious matter which might generate negative consequences for him by alienating family and friends; this colleague was Jewish. So I suggested that he talk to his Rabbi to see if he might be able resolve his search within his own tradition first.

Needless to say, my colleague did not convert. But as soon as my secretary got wind of everything, I incurred the full force of her unbridled wrath. She actually went to great lengths to spread ugly rumors and even sabotage my work at that particular firm. It was a very unpleasant experience.

BTW, Father Al, I think that you showed remarkable patience and restraint in the way in which you responded to Mr. Truglia’s baseless claims. You are a paragon of integrity and Christian charity!!

LikeLike

Patience and restraint are virtues we ought to recognize as common to Christians; the tone of these pieces speaks as strongly as any argument made. In any case, Truglia is just a kid. He will grow out of this stuff – a calm and gentle reply will only hasten that.

LikeLiked by 1 person