by Brian C. Moore, Ph.D.

thinking about jesus and

i believe i do. I believe, at least (i believe i believe)

in what he believed in.

i believe, at least, that he got where he was going,

and that where he was going is exactly where i

should like to go.

our identity is bound with our memories: wash away

memory and identity disappears…

only to reappear again with our next action.

i remember the people i loved (who have died) or

who’ve just disappeared – remember their traits

as though it were a sacred duty.

what possible use for all those memories

unless we were (somehow)

all to meet again?

(Robert Lax, Contemplative word # 60, In the Beginning Was Love)

Michel Henry’s phenomenology is a strange bird. I find myself by turns exasperated, intrigued, cheering, and then decrying the fella as a modern-day Cathar. One of the aspects of his thought that I like is his insistence on Life as unique and his situating of subjectivity as ultimately Christological. I surmise some critics think he is just translating his own philosophy into theological terms. I translate Henry’s Life as akin to uniquely divine Existence. Creatures participate in both analogously. Regardless, what I want to touch upon now may seem a banality, it is so obvious. It is so evident that Henry feels it necessary to point it out. I suppose it is helpful to know that Henry thinks divine life as “auto-affective.” Feeling is not directed to an “outside.” Henry’s truth is acosmic, so that the “appearance” that constitutes worldly truth is essentially a lie. This gets rather squirrelly and difficult and I’m not interested in hashing it out here. What does interest me is what Henry has to say about the poet:

Human speech says by showing in the world. Its manner of saying is a make-seen, that make-seen that is only possible within the horizon of visibility of the “outside.” … 1. It gives itself by showing itself outside in a world, in the manner of an image. 2. It gives itself as unreal. Let us consider the first verse of Trakl’s poem entitled “A Winter Evening”:

Window with falling snow is arrayed,

Long tolls the vesper bell,

The house is provided well,

The table is for many laid.The things referred to – the snow, the bell, the evening – named by the poet and called into presence by their names, are shown to our minds. Yet they do not take a place among the objects surrounding us, in the room where we are. They are present, but in a sort of absence … This is the enigma of the poet’s word … it gives the thing but as not Being. (I Am the Truth, pp. 218-219)

We are so used to this, it hardly seems worthy of remarking. Folks would be disconcerted should Hamlet’s ghost suddenly appear in their bedchamber. But ultimately, Henry wants to bring judgment on all human speech. The creature’s words are not merely impotent, they are inherently guilty, gesturing towards that which is a permanent absence. (Let us leave aside all the post-modern angst over presence and nostalgia and the like. None of that understands the gift or a dynamic eternity or much of anything at all, to be honest.) Thus, Henry: “Speech’s powerlessness to bring into existence what it names is not due to chance, to some exterior and contingent obstacle. It is the very way it speaks that de-realizes in principle everything of which it speaks … strips it of its reality, leaving behind only empty appearance” (p. 219).

Against this pessimism, I want to set some thoughts of Eugen Rosenstock-Huessy. Before doing so, however, allow me to say that there is more than an intellectual stunt behind Henry’s critique of the poet. I think he expresses in a different key Plato’s objection to the mimesis of the poet. Both detect illusion in the artist that prevents encounter with the real (and here, more broadly interpreted, all men are artists, all their words pointed towards images that may betray or imprison.) This is not at all Plato’s last word on the poet, but ambivalence towards human language is noted. Rosenstock-Huessy wryly observes in The Origin of Speech that “the indicatives of language are the concessions to the scientific or reflective mentality. Yes, we may say `2 plus 2 is 4,’ we may say: `The Mississippi is the largest river in the United States.’ … The reflective mood surveys facts which can be labeled and defined, and Horace makes fun of it” (p. 38). I think the logicians who refuse the analogical gap between God and creatures, the ones who try to confine God to a Euclidean logic and measure divine freedom by concepts derived from the imperfect experience of fallen men, these would not laugh. If you like, there is a continual forgetting of what is real and what is provisional, on the way. We are pilgrims in status via and so the wise use of language must always remember the silent plenitude from which the word arises. “The meaning of meaning is not discovered by defining our terms. Our semanticists are alright when they apply their method to dead words of the past. They are gravediggers. They are quite helpless with regard to the names …” (p. 35). Yes, let the dead bury the dead. Whereas we are asked to be daring. There’s this thing about names that utterly escapes the nominalists for whom trivial convention is the apex of their intellectual achievement. “Names are promises to be acted upon” (p. 34). To be gifted a name is to be given a vocation barely discerned and beyond calculation. “Names, to the initiated adolescent were promises of a slow ascent to understanding. They were shrouded in mystery, not because they were not true but because they were meant to come true” (p. 37). And most importantly, “There are … no other living names but ‘theophoric’ ones” (p. 36). In Speech and Reality, Rosenstock-Huessy declares that “man’s real action is contained in the myth-weaving or truth-disclosing business. This is our action. For the rest we belong to nature” (p. 76). Once again, the counter-cultural impetus of “insight into image” and Goethe’s “listening” and Desmond’s metaxological porosity to things that metaphorize themselves into symbolic speech of the mysterious Origin, of Pickstock’s sign-bearing things that bump up unpredictably into meaningful juxtaposition asks of us a serious discernment between imagination rooted in what I would call prayerful openness and the kind of Gnostic imagination that runs rampant today. The former makes possible real action, while the latter is what Henry dismisses as terminal failure radically at odds with life as the power to give Being.

I prefaced this section with a brief rumination from Robert Lax, who was Thomas Merton’s great friend. Lax was eccentric, innocent, guileless, often astute to the Spirit. He once spent a fortnight in what he mistook for a hostel before realizing it was a bordello. He was that kinda fella. Lax spent the last part of his life living on the island of Patmos where he wrote disarming, simple poems that flash contemplative depths. He isn’t voicing triumphalism in the bit I quoted, but you’re missing it if you think it is skirting the line of skepticism or evincing a low Christology. But notice: the interlocutors questions about the victory of Christ are turned to memory and identity and the reverent service we offer to the dear ones by refusing to forget. Rosenstock-Huessy understands this as a communal piety. “I possess memories in the plural only, loves, desires, observations. The whole race is making up for my forgetfulness, my indifference, my fears, my madness. Mankind has a destiny, an origin, a self-revealing art …” (Speech and Reality, p. 63). History is disclosure only when it is memory made meaningful by passionate attachment. “Our fears while we listen to the tale are: will they obey their highest calling. If the tale ends in woe, it actually has not ended. It follows us into our dreams; it remains with us and we shall have to do something about it” (p. 55). That last is the Ecclesial challenge, the place where one must see who treats the gospel as written in the indicative and who attends to the silent artistry of the Comforter even now transforming horrors into the life of Christ. Catherine Pickstock hints at what I am after in Repetition and Identity. “It is too soon to say . . . what the French Revolution really means; it will always, in time, be too soon. We must await the final judgment, which is already made” (p. 100).

Bulgakov asks us to imagine a metaphysical reality beyond the deathward dispersion of what Paul Griffiths describes as “metronomic” time. Time as gift, as room for delightful event, time as God intends it for eternal wedding feast reveals a very different community from that conceived as an array of individuals passing on genetic information before an inevitable mortality. “In its idea the genus exists both as one and as the fullness of all its individuals, in their unrepeatable particularities, with this unity existing not only in abstracto but also in concreto” (Unfading Light, p. 236). Such unity demands an eschatological horizon where one lives and loves eternally. Within that horizon, the spousal truth of all being is manifest. Grace radiates iconicity.

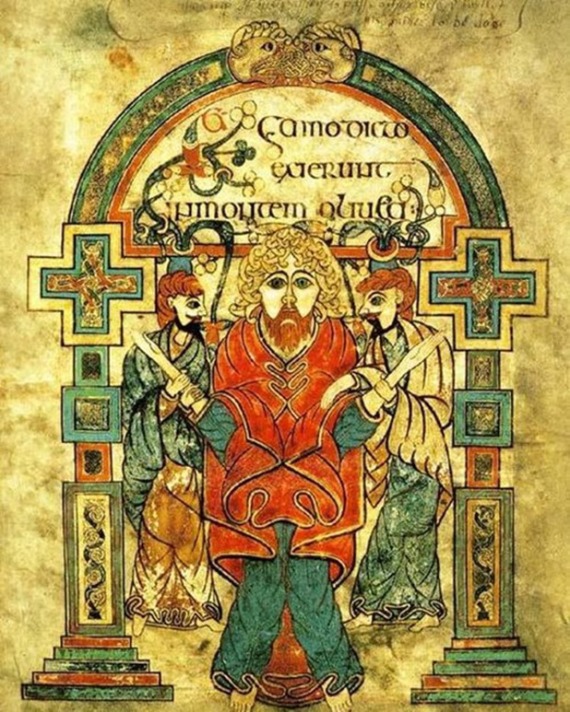

In totems, coats of arms, and sacred images this ideal reality of genus is symbolically expressed: a wolf exists not only as the totality of wolves but also as wolfness, as does a lion and lioness, a lamb and lambness; there is a rose that blooms in Sophia and a lily of the Annuncation; there is gold, frankincense, and myrrh, which are suitable for presentation to the infant boy of Bethlehem, not all by arbitrary selection but by their inner nature. An icon such as the image of the Theotokos in the fields, surrounded by sheaves of rye, speaks of this, or the so widespread symbolism of animals in iconography. (p. 236)

An economy based on scarcity which is synonymous with time as a dwindling, mortal element provokes the fear of Kierkegaard’s aesthete who must renounce plenitude with decision. Such thrift is an accommodation to diabolic illusion, even if we all experience it existentially in this world. Those who labor under the impression that it is a perduring rule for life are akin to those Sadducees who sought to test Jesus by inquiring about the marital status of the resurrected woman married sequentially to seven brothers. (You wonder how many brothers in before the next fella up started to wonder if Moses had left an escape clause.) The pleroma of eschatological humanity was simply beyond their imaginative capacity. But something like ecstatic plenitude is intuited by General Loewenhielm in a famous speech that marks the wise crescendo of Isak Dinesen’s “Babette’s Feast.” (I was going to make a brief allusion, but what’s one more long quotation, eh?)

“Man, my friends,” said General Loewenhielm, “is frail and foolish. We have all of us been told that grace is to be found in the universe. But in our human foolishness and shortsightedness we imagine divine grace to be finite. For this reason we tremble…” Never till now had the General stated that he trembled; he was genuinely surprised and even shocked at hearing his own voice proclaim the fact. “We tremble before making our choice in life, and after having made it again tremble in fear of having chosen wrong. But the moment comes when our eyes are opened, and we see and realize that grace is infinite. Grace, my friends, demands nothing from us but that we shall await it with confidence and acknowledge it in gratitude. Grace, brothers, makes no conditions and singles out none of us in particular; grace takes us all to its bosom and proclaims general amnesty. See! that which we have chosen is given us, and that which we have refused is, also and at the same time, granted us. Ay, that which we have rejected is poured upon us abundantly. For mercy and truth have met together, and righteousness and bliss have kissed one another!”

I rather doubt that Dinesen actually believed in the eschatological reality that makes sense of her General’s words, but poets often garner more truth than they intend.

I’m very fond of Plato. He’s the most congenial pagan thinker, in my view. His Socrates was surely placed providentially so that his life might act covertly as John the Baptist to the gentiles. That is my private speculation, but whether one entertains that or not, no one can credibly dispute that Plato is a master artist which is why those who uncritically accept the exile of the poets from the ideal Republic must account for an obvious contradiction. The answer, as David C. Schindler argues in Plato’s Critique of Impure Reason, lies in the transformative role played by the concluding myth of Er upon the dialogue as a whole. One has to remember that Plato’s project is driven by the life and death of Socrates. It is particularly the death of Socrates at the hands of the Athenian bien pensant that drives him to seek justice and to reconcile the horror and anguish of loss with the mysterious Agathon. Schindler persuasively asserts that Er is a stand in for Socrates. Like Er, Homer’s Odysseus has journeyed in the Underworld and returned to the living. The sly cunning of Odysseus, however, is not altered by such an adventure (so much is he not changed that Straussians and other skeptics believe the whole episode a bit of wily yarn-spinning.) Regardless, Odysseus remains “a master of deception” who aims “primarily at glory.” In contrast, Er/Socrates “has `recovered from love of honor’ through ‘memory of my former labors,’ i.e., because he has suffered through the whole of human experience and is now in a position to view it from an eternal perspective” (pp. 330 – 331). This is recalled in Desmond’s concept of posthumous mind. Desmond asks one to imagine one is thrown into the future beyond one’s mortal years. How differently would one look upon the cosmos as if from beyond death? “Beyond the instrumental relation of means and end, posthumous honesty would serve nothing but the praise of the worth of being, of truly worthy being . . . Posthumous mindfulness makes us wonder about what we so love now that its loss or desecration would grieve us to the roots on our restoration to life” (The Intimate Strangeness of Being, pp. 294-95). Anxiety, envy, ill-will, ambition, the petty maladies of soul sickness destroy vision. For these, death is the cure that restores sight. Schindler notes, “By being allowed to return to life without drinking from the river Lethe, Er carries the ‘eschaton’ back with him into this world. His return is, so to speak, the entry of the infinite into the finite, the insertion of the ‘beyond’ into the ‘here and now'” (p.333).

I’d like to think about what happens to time for the posthumous? Time is no longer running inexorably through the hour-glass. That kind of time, time as a product of scarcity, has died with death. My argument is that Socrates’ daimon, the spirit that I suspect was his guardian angel, the one that would leave him standing in a field for hours contemplating whilst others puzzled over him as they passed by on serious matters, had already drawn him into a temporality beyond this world of ruin. Hence, Socrates’ actions, his mode of quest, are already implicitly eschatological and dependent on an everlasting time that does not know famine. Schindler specifies that the sophists are inevitably associated with efficiency. “Plato regularly emphasizes speed when he refers to sophistry. ‘But the greatest thing of all,’ Socrates tells a couple of sophists, ‘is that your skill is such, and is so skillfully contrived, that anyone can master it in a very short time'” (p. 261). Quickness to adapt and readily apply skill can also be thought as indicative of Michel Henry’s poet. It doesn’t take very long to conjure an entire ocean or nation or world. One need only jot down the words. So, maybe in all this there is a common element. Socrates thinks the chief vice of the sophists is that they are always in a hurry. (They are the opposite of Ents.) Indeed, Socrates grants that the sophist has attained a technical ability that surpasses the ancient thinkers. Yet it is a false triumph: “this both makes wisdom a ‘skill’ and makes it subservient to ends other than itself, i.e., practically useful. Sophists are never therefore wise because it is good to be such, but always simply as ‘wise as they need to be'” (p. 268). The expedience of that last line is of course the virtue of a strumpet. I believe this is what they tout nowadays as “transferrable skills” as a means of making the liberal arts relevant. Meanwhile, Socrates the annoying gadfly, the poor man who is constantly trying to drag folks into endless dialogues about useless questions devoted to what everybody already knows is decidedly not interested in what makes a thing useful. A paradox emerges. Schindler asserts that Socrates’ leisure is the flower of an ardor that transcends the limited desires of practical men:

Freedom from time implies in another respect a greater responsibility to time, which expresses itself existentially as a certain patience. Desire for the goodness, i.e., the real reality, of a thing is a desire for the whole of it. But though the whole is revealed in one respect “in a flash,” in another respect it does not show itself all at once but takes time. Something great, Plato explains, cannot come to be in a short time. (pp. 263–64)

The beautiful is loved for its own sake. Moreover, beauty is the radiance of goodness, the witness of truth. It remains to be said that the poetry of Er may also be written in words, at least sometimes. The difference is that language that comes from long acquaintance compactly references what takes not only a vast amount of time, but the whole of a lifetime. Only from the deepening of eschatological insight is the name of the beloved discerned. Participation in divine delight is the necessary flourishing from which one can recognize the transient cosmic expressions of even a world marked by death as fundamentally rooted in generosity. The image is not an empty signifier as Henry seems to fear. Rather, forms are made more full and loveable by the images that spark from them as living fires.

“When Jesus takes our human nature, it does not become less, but more human, and it is made more by its contact with God, the very source of all being, and this intensification of Jesus’ human nature must be understood not only in a personal sense, but in a social one, as well,” states James Arraj (Mind Aflame, p.33). Sherrard adds “Human potentialities go infinitely beyond the parameters of any kind of perfection we can visualize as possessing on our own account or that can be actualized without divine intervention and guidance” (Christianity, p. 12). And this is S. L. Frank: “Outwardly, the human personality appears to be self-enclosed and separated from other human beings, but, inwardly, in its depths, it communicates with all other beings, is fused with them in primordial unity” (The Meaning of Life, p. 90). Last, here is Bulgakov: “Christ is a human being as such, the whole idea of the human, and in this sense the genus in the human being … If it were possible to look from within at the family, the clan, the nation, humanity, all of this would be presented as a single, many-faced, many-eyed entity” (Unfading Light, p.236). Of course, this sense of ontological solidarity is an interpretation. It is certainly not a given available through demonstration or the logic of univocal philosophers. Yet it is the fundamental secret entrusted to the Church — and so often betrayed. Holiness is not a judgment from the outside. It is the leaven of Christ healing and empowering from within. Generations of Christian belief have softened the existential vertigo of the Passion. Folks like to condescend about Peter, that rough fisherman who was brave enough to follow Christ so far as the court of the high priest, but then faltered. When Pilate asks the bedraggled, country prophet from a benighted and troublesome province “what is truth?” all the weary experience of antique civilization shrugged before the dreamy inconsequence of any answer. Even Christ’s family had wondered if he was mad. The death-bound world, the world of violence and power, has not left off condescending dismissal. The line between a sovereign and kingly patience that bears everything in order to attain the “it is good” of creative victory and an impotence that simply permits everything can be impossibly obscure from the side of shadows and tears. The courage of ecclesial existence is to dare to tell the story of God’s impossible love, which is the story of us.

* * *

Dr Moore has a Ph.D. in literature from the University of Dallas. He has been a contributor to Eclectic Orthodoxy since before the beginning of time. There is, it must be said, no truth to the rumor that he comes from a family of Druids or that he will drink only plum wine, though it is possibly true that he prefers cats to humans, allowing for exceptions. He is the author of the recently published tale of Noah and the ark, Beneath the Silent Heavens.

Thank you, Brian, for this wonderful series!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Truly, this series has been a delight to encounter. Many thanks for the reflections. (And though you weren’t looking for laurels, I think you deserve one for the LOTR reference.)

“Man is the revelation of the Infinite, and it does not become finite in him. It remains the Infinite.” -Mark Rutherford

“Or am I there already, and it is Paradise to look on mortal things with an immortal’s eyes?” – AE The City

LikeLiked by 1 person

Mysteries herein I don’t understand, like when I was reading Wolfgang Smith a few days ago. “There are more things in heaven and earth…”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Now be so good as to knit it all together into a small book.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Thanks for the kind words, old friends and new. My limited leisure is generally devoted to a novel that thematically ties very much into the substance of these reflections. I take note of the suggestion, however, and will see about the knitting.

LikeLiked by 2 people