As readers of Eclectic Orthodoxy know, my wife and I offer the Office of Matins each day from the Holy Transfiguration Prayer Book. We like its structure, rhythm, and balance. It only provides one psalm, so we substitute others from the Psalter, which we are reading in course. It all works quite nicely.

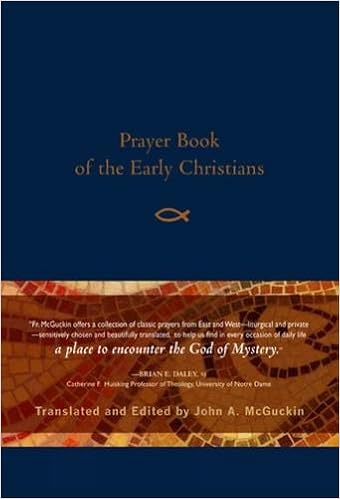

Recently, we have begun incorporating into our morning prayers one of the Twelve Prayers of Dawn from the Prayer Book of the Early Christians. And that brings me to the point of this post. I strongly recommend this little book not only to Orthodox Christians but to everyone who might feel drawn to pray the Eastern Offices. Edited by the fine patristics and Byzantine Christianity scholar Fr John McGuckin, this is a high quality hardcover at an affordable price (with ribbon!). The prayers are presented in contemporary but dignified language, which is a plus for some and a negative for others. I tend to prefer a traditional idiom (thee’s and thou’s and that sort of thing), but I know I’m in an ever-diminishing minority, particularly when it comes to the offering of prayers in one’s home. Regardless, all will find this book useful.

Recently, we have begun incorporating into our morning prayers one of the Twelve Prayers of Dawn from the Prayer Book of the Early Christians. And that brings me to the point of this post. I strongly recommend this little book not only to Orthodox Christians but to everyone who might feel drawn to pray the Eastern Offices. Edited by the fine patristics and Byzantine Christianity scholar Fr John McGuckin, this is a high quality hardcover at an affordable price (with ribbon!). The prayers are presented in contemporary but dignified language, which is a plus for some and a negative for others. I tend to prefer a traditional idiom (thee’s and thou’s and that sort of thing), but I know I’m in an ever-diminishing minority, particularly when it comes to the offering of prayers in one’s home. Regardless, all will find this book useful.

And remember—be flexible. If you find, say, Vespers too long, then trim it down until it becomes an office that works for you. In the oft-quoted maxim of Dom John Chapman: “Pray as you can, not as you can’t.” The monks in heaven are not grading you. The important thing is to pray.

The best part is the Amazon description of the author of the The Prayer Book of the Early Christians– John A. McGuckin (Creator)

I always suspected it was true. But now Amazon confirms it.

http://amzn.to/2dOkJlZ

LikeLike

What was true?

LikeLike

John A. McGuckin is the Creator! He’s certainly written enough. 😊

LikeLike

One nitpicky note, the HTM Morning Prayers don’t actually correspond to Matins. If you look, there is an order of Matins contained in the HTM book as well. Morning Prayers generally correspond to the Midnight Office, as an extremely abbreviated form, or replacement, of it.

LikeLike

Old Anglican habits. 😊

LikeLike

I left the Grail Psalms behind gratefully when I left behind by Christian Prayer breviary. I could never go back. May be a terrible fault that I have but there it is.

LikeLike

Someone help me out here because I spoke too soon and too briefly earlier, about the Grail Psalms. To me the Grail Psalms sound and feel watered-down in my mouth. They are difficult, I think, to chant and leave me, at the end, wanting more than I got from the saying of the Psalm…any of the Grail Psalms. But they are pervasive in many ways and people like them…really them…like them with the same intensity that I dislike them. So what is it about them that draws people to them? Wax eloquent; I don’t mind nor will I think you silly for doing so. Help me to see in them what you who appreciate them see in them.

LikeLike

I have no idea what the Grail Psalms are. Sounds like I don’t want to know.

LikeLike

Fr John uses the Grail Psalms for the psalm texts in this book. (I have no experience with them myself so can’t comment either way about them).

LikeLike

Thanks for the explanation.

LikeLike

A great word! Pray as you can and not as you can’t.

LikeLike

The Grail Psalms are the standard for the divine office in the Latin rite. They are said to be a modern language translation of the Psalms that make them more accessible to people. Compared to the Jordanville Horologian, I think that the psalms in the Christian Prayer breviary are, superficially, more familiar to the contemporary English-speaker’s ear. But I also think that much is lost by way of more meaty grammar and syntax, and that meat is worth the extra effort to adjust one’s ear to the less familiar manners of the older constructions/translations.

LikeLike

That explains my ignorance. I’ve never offered the Divine Office according to the Latin Rite.

LikeLike

I’ve wavered a lot on the question of “hieratic” English versus contemporary English, but I feel pretty confident at this point that the use of archaic grammar/ syntax/ diction, while a legitimate literary device for giving a venerable aura to a text, is not essential for this purpose, and that, if the translator/ writer knows what he’s doing, a prayer rendered in contemporary English can sound exalted and elevated in its own right. Of course a lot of our prayers are translated in a pedestrian way, but I think the fault for this has more to do with translator’s lack of poetic sense than their avoidance of archaism. Archaism is not immune to falling flat; IMO the “Spiritual Psalter” of Saint Ephraim, in its English translation, is an example of a text in “hieratic” English but largely lacking musicality.

LikeLike