by Sinner Irenaeus (Brad Jersak, Ph.D.)

“That is all I ask of Orthodoxy—to permit me to hope.” — Fr. Aiden Kimel

After a decade of catechesis and struggle under the guidance of my spiritual father, Archbishop Lazar Puhalo, and godfather, David Goa, I was chrismated into the Orthodox Church in 2013. To some, the tutelage of these sages already disqualifies me, the rhetoric of unity of the Church notwithstanding. But I knew this. I proceeded with eyes wide open into the Orthodox Church despite her conflicts and dysfunctions. I proceeded because I felt drawn from my Evangelical foxhole into the harbor of Christian Orthodoxy, where I was exposed to a more Christlike God.

A key factor in the move was the assurance of some key Scriptures, catechisms and liturgies, along with a number of significant Orthodox saints, hierarchs and theologians, that Orthodoxy permits me to hope—that I could believe and teach my basic conviction (published in Her Gates Will Never Be Shut) of a humble eschatological hope, the possibility in principle of universal salvation—without being branded a heretic.

Not that I make the bold claims of St Gregory of Nyssa or St Isaac of Syria (their revised apokatastasis have never been anathematized). Nor do I insist on teaching the daring universalism of Fr. Sergius Bulgakov or David Bentley Hart as doctrine (although their arguments seem airtight).

My own project is far more modest. I ask and now assert that Christian Orthodoxy permits me to hope—permits a position elsewhere called “hopeful inclusivism.” Hopeful inclusivism says that we cannot presume that all will be saved or that even one will be damned. Rather, we put our hope in the final victory and verdict of Jesus Christ, whose mercy endures forever and whose loving-kindness is everlasting.

An incontrovertible fact of our tradition is that Orthodoxy at least permits (and may even require) us to hope, pray, preach and work for the salvation of all. Some Orthodox (usually convert priests) insist, like the shrinking majority of my Evangelical brethren, on the necessary and inevitable eternal damnation of the greater part of humanity. That position is permitted. It is easy enough to find the threat of eternal conscious torment within some of the Fathers, synods and traditions—even some Scriptures. But the infernalists cannot rightly deny the stubborn fact that Orthodoxy has and does also provide a harbor for those who ask only, “Permit me to hope.”

Those who embrace hope for a universal redemption should not be charged with heresy or a failure of Orthodoxy, given the irrepressible stream within the Tradition that runs through ancients such as Clement of Alexandria, St Macrina, St Gregory Nyssen, St Isaac of Nineveh (and other Fathers), and among moderns including Fr. Sergei Bulgakov, St Silouan the Athonite, Fr. Alexandre Turincev, Metropolitans Kallistos Ware and Hilarion Alfeyev, et al.

If Kallistos Ware, for example, is truly Orthodox, then I must be permitted the same hope he articulates in his essay, “Dare We Hope for the Salvation of All?” If I can be shown to disagree with his eminence on a single point of eschatology, I will gladly and swiftly repent (although he confirmed my understanding of his hope in person). Those who deny the orthodoxy of Ware’s hope are free to do so, but I will happily hide in the theological folds of his cassock. To repudiate anyone’s Orthodoxy on the basis that they hope that Christ will in fact be the Savior of all is simply not very Orthodox.

Now some of my universalist friends will say, “Yes, but ours is more than hope … we know by faith that this salvation will ultimately redeem all of God’s creatures.” I honor that conviction. I find it compelling and could even privately hold it. I’m personally just not able or allowed to teach it as doctrine. Hence my retreat to the language of hope, where I think we can make a strong case against all challenges to its Orthodoxy. My burden of proof is not that universal salvation should be doctrine (I leave that to others), or to refute strands of Orthodoxy that resist it. I need only maintain and demonstrate that hope for ultimate redemption is actually permitted.

With that long, rather defensive preface out-of-the-way, I am prepared to give an answer to those who have asked me to give the reason for the hope that I have. Please forgive me where I fail to do so with sufficient gentleness and respect.

The Scriptures Permit Me to Hope

First, the Scriptures (still central to the Orthodox tradition) permit me to hope. It is possible that when the Bible refers to Christ as Savior of all, they may actually mean he is Savior of all. I understand that theologians and commentators of Augustinian/Calvinist descent regard all in the limited sense of all of the elect. And some Scriptures do imply that all refers only to all who believe. But some texts say clearly, without caveat, that the all-embracing redemptive love of Christ includes all humanity, the entire world (cosmos) and the whole of creation.

What follows is a catena of biblical texts that together describe the scope of God’s salvation. This is not merely an exercise in proof-texting or “text-mining,” as some like to call it. A catena, in this case, is a chain of Scriptures strung together as commentary on the theme of God’s saving work for all—the grand arc of God’s drama of redemption. When read aloud with a touch of gravitas, rather than skimmed, mentally footnoting refutations, the momentum is impressive:

And then all flesh shall see the salvation of God (Lk 3:6).

This man came for a witness, to bear witness of the Light, that through him all might believe (Jn 1:7).

Behold, the Lamb of God that takes away the sin of the world (Jn 1:29).

For God so loved the world that He gave His only begotten Son, that whoever believes in Him should not perish but have everlasting life. For God did not send His Son into the world to condemn the world, but that the world through Him might be saved (Jn 3:16-17).

The Father loves the Son, and has given all things into His hand (Jn 3:35).

We no longer believe because of what you said, for we have heard for ourselves and know that this really is the Savior of the world (Jn 4:42).

For the bread of God is the bread that comes down from heaven and gives life to the world (Jn 6:33).

I am the light of the world (Jn 8:12).

And I, if I am lifted up from the earth, will draw all men to Myself (Jn 12:32).

Jesus knew that the Father had given all things into His hands (Jn 13:3).

All that the Father gives Me will come to Me, and the one who comes to Me I will by no means cast out. This is the will of the Father who sent Me, that of all He has given Me I should lose nothing, but should raise it up at the last day (Jn 6:37, 39).

For you granted him authority over all people that he might give eternal life to all those you have given him (Jn 17:2).

Heaven must receive him until the time comes for God to restore all things (Acts 3:21).

He made known to us the mystery of His will, according to His good pleasure which He purposed in Himself, that in the dispensation of the fullness of the times He might gather together in one all things in Christ, both which are in heaven and which are on earth—in Him (Eph. 1:9-10).

And He put all things under His feet, and gave Him to be head over all things to the church, which is His body, the fullness of Him who fills all in all. (Eph. 1:22-23)

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn over all creation. For everything was created by Him, in heaven and on earth, the visible and the invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things have been created through Him and for Him. He is before all things, and by Him all things hold together … and through Him to reconcile all things to Himself by making peace through the blood of His cross—things on earth or things in heaven (Col. 1:15-17, 20).

As through one man’s offense judgment came to all men, resulting in condemnation, even so through one Man’s righteous act the free gift came to all men, resulting in justification of life (Rom. 5:18).

For from him and to him are all things (Rom. 11:26).

He has shut up all to unbelief so that he might have mercy on all (Rom. 11:32).

For as in Adam all die, so also in Christ all will be made alive (1 Cor. 15:22).

Then comes the end, when He hands over the kingdom to God the Father, when He abolishes all rule and all authority and power. For He must reign until He puts all His enemies under His feet. The last enemy to be abolished is death. For God has put everything under His feet. But when it says “everything” is put under Him, it is obvious that He who puts everything under Him is the exception. And when everything is subject to Christ, then the Son Himself will also be subject to the One who subjected everything to Him, so that God may be all in all (1 Cor. 15:24-28).

At the name of Jesus every knee will bow—of those who are in heaven and on earth and under the earth—and every tongue should confess that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father (Phil. 2:10).

He will transform the body of our humble condition into the likeness of His glorious body, by the power that enables Him to subject all things to Himself (Phil. 3:21).

He desires all people to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth (1 Tim. 2:4).

We labor and strive for this, because we have put our hope in the living God, who is the Savior of everyone, especially of those who believe (1 Tim. 4:10).

For the grace of God that brings salvation has appeared to all men (Tit. 2:11).

He appointed the Son heir of all things, and through whom also he made the universe.in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed heir of all things (Heb. 1:2).

He is not willing that any should perish but that all should come to repentance (2 Pet. 3:9-10).

He Himself is the atoning sacrifice for our sins, and not only for ours, but also for those of the whole world (1 John 2:2).

I heard every creature in heaven, on earth, under the earth, on the sea, and everything in them say: Blessing and honor and glory and dominion to the One seated on the throne and to the Lamb, forever and ever! (Rev. 5:13).

Then He who sat on the throne said, “Behold, I make all things new” (Rev. 21:5).

Again, these passages are not random beads gathered into one convenient lump. They represent the Christotelic purposes of God from Alpha to Omega. Many of them speak of a salvation given, not merely offered, to all, not merely the elect. They are the promise of the Good Shepherd who leaves the ninety-nine to seek and to save the lost sheep until he finds it (not just until the die).

In Revelation 1, we find the risen Christ, victorious over death, holding the keys of death and hades. It begs the question: if Christ holds the keys to death and hades, what do we believe he shall do with them?

The Scriptures allow me to hope that in the height, width, depth and length of God’s love for us—a love only grasped through the empowering illumination of the Holy Spirit—something more magnificent than I could either ask or imagine awaits us all (Eph. 3:14-21).

Competing interpretations and counter-texts do abound. But they do not negate the hope Scripture permits me.

The Fathers Permit Me to Hope

When referring to “the Fathers,” we cannot pretend they were of one mind on any given topic, least of all eschatology. I am sure that for every citation I offer from the Fathers for hopeful inclusivism, others can counter with a goodly list of their own, more infernalist references. My citations disprove nothing; nor do theirs. But what we can demonstrate that some of the great Fathers and Mothers either hinted at or taught publicly their hope (and in some cases, their firm conviction) that all might or would be saved at the last.

I will dispense quickly with the controversies surrounding Origen, his particular account of apokatastasis and the controversies surrounding the anathemas directed as later Origenism. Suffice it to say that I have not seen a remotely convincing refutation of David Bentley Hart on the topic.[1] In fact, he seems to echo the growing consensus. Nevertheless, I will completely concede that point and proceed only with those recognized officially as Fathers or Mothers and saints of the Church.

For brevity sake, I won’t even summarize the work of others who have gathered citations from a good number of the Fathers.[2] To my mind, some are a stretch, but I would mention just a few who have impacted me.

- Clement of Alexandria

Clement (150-c.215) was head of the catechetical school in Alexandria. His Stromata take us to his central beliefs. He offered to initiate the educated into “complete knowledge.” The following passage is typical of his redemptive hope:

Clement (150-c.215) was head of the catechetical school in Alexandria. His Stromata take us to his central beliefs. He offered to initiate the educated into “complete knowledge.” The following passage is typical of his redemptive hope:

The Saviour also exerts His might because it is His work to save; which accordingly He also did by drawing to salvation those who became willing, by the preaching [of the gospel], to believe on Him, wherever they were. If, then, the Lord descended to Hades for no other end but to preach the Gospel, as He did descend; it was either to preach the Gospel to all or to the Hebrews only. If, accordingly, to all, then all who believe shall be saved, although they may be of the Gentiles, on making their profession there; since God’s punishments are saving and disciplinary, leading to conversion, and choosing rather the repentance them the death of a sinner; and especially since souls, although darkened by passions, when released from their bodies, are able to perceive more clearly, because of their being no longer obstructed by the paltry flesh.[3]

Notice the main features above: (i) the Saviour is mighty to save; (ii) through preaching the gospel; (iii) even posthumously in hades; (iv) where the ‘punishments’ are saving and disciplinary; (v) leading to repentance and conversion; (vi) because death has freed them to perceive. Clement hopes that all will respond and he permits me to hope.

- St Gregory of Nyssa

Even after the sixth century condemnation of Origenism, commonly attributed to the Fifth Ecumenical Council (553), the Seventh Ecumenical Council (787) referred to St Gregory of Nyssa (c.335-c.395) as “father of the fathers” and “divine luminary of Nyssa.” Notably, no council ever condemned Gregory or his revised apokatastasis. In On the Soul and the Resurrection he taught ultimate redemption more boldly than Origen. And far from being a minor blemish on the fringe of his theology, Gregory’s universalist theosis permeates the whole and is central to it. For those who care to hear his blessed hope, this sample from his treatise on 1 Cor. 15:28 is typical:

Even after the sixth century condemnation of Origenism, commonly attributed to the Fifth Ecumenical Council (553), the Seventh Ecumenical Council (787) referred to St Gregory of Nyssa (c.335-c.395) as “father of the fathers” and “divine luminary of Nyssa.” Notably, no council ever condemned Gregory or his revised apokatastasis. In On the Soul and the Resurrection he taught ultimate redemption more boldly than Origen. And far from being a minor blemish on the fringe of his theology, Gregory’s universalist theosis permeates the whole and is central to it. For those who care to hear his blessed hope, this sample from his treatise on 1 Cor. 15:28 is typical:

What therefore does Paul teach us? It consists in saying that evil will come to nought and will be completely destroyed. The divine, pure goodness will contain in itself every nature endowed with reason; nothing made by God is excluded from his kingdom once everything mixed with some elements of base material has been consumed by refinement in fire. Such things had their origin in God; what was made in the beginning did not receive evil. Paul says this is so. He said that the pure and undefiled divinity of the Only-Begotten [Son] assumed man’s mortal and perishable nature. However, from the entirety of human nature to which the divinity is mixed, the man constituted according to Christ is a kind of first fruits of the common dough. It is through this [divinized] man that all mankind is joined to the divinity.[4]

Those who think to deny the Orthodoxy of the final editor of the Nicene Creed ought not tread where the 5th council dared not. As for me, at the least, St Gregory of Nyssa permits me to hope.

- St Isaac of Nineveh

![]() St Isaac (c.613-c.700) represents a Syrian monasticism filled with love, derived from the monk’s own mystical encounters with God. When Kallistos Ware dips most deeply into the well of hope, he draws from the words of St Isaac (citing Isaac from Ware’s “Dare We Hope?”):

St Isaac (c.613-c.700) represents a Syrian monasticism filled with love, derived from the monk’s own mystical encounters with God. When Kallistos Ware dips most deeply into the well of hope, he draws from the words of St Isaac (citing Isaac from Ware’s “Dare We Hope?”):

It is wrong to imagine that the sinners in hell are deprived of the love of God … [But] the power of love works in two ways: it torments those who have sinned, just as happens among friends here on earth; but to those who have observed its duties, love gives delight. So it is in hell: the contrition that comes from love is the harsh torment.[5]

Isaac believes the scourgings of love will come to a good end and “wonderful outcome”—for two reasons. First, because retribution is foreign to God’s nature. “Far be it, that vengeance could ever be found in that Fountain of love and Ocean brimming with goodness!”[6] And second, God’s love is unquenchable and all-powerful, so it is able to overcome evil and extend to all creation and through all eternity to everyone: “No part belonging to any single one of [all] rational beings will be lost.”[7]

Strong words. Bold convictions. And while we might stop short of Isaac’s confidence, he certainly encourages us to hope.

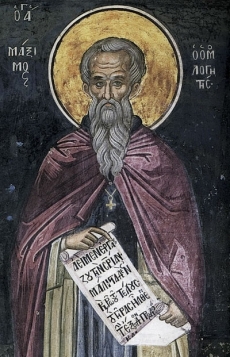

- St Maximus the Confessor

We complete our quartet of sample Fathers with the beloved and courageous St Maximus the Confessor (c. 580-662). Aside from my love for Maximus, I chose to include him precisely because he should not be cited as a universalist with certitude.[8] Maximus foresees how Christ will, at the end, restore humanity’s natural will and our capacity to desire only the good. Even so, he makes space for the necessity the humanity must, on its part, willingly engage that capacity. Thus, Maximus represents well the distinction between automatic universalism and the possibility that all will respond in the end. But listen to how confident he is of said possibility!

We complete our quartet of sample Fathers with the beloved and courageous St Maximus the Confessor (c. 580-662). Aside from my love for Maximus, I chose to include him precisely because he should not be cited as a universalist with certitude.[8] Maximus foresees how Christ will, at the end, restore humanity’s natural will and our capacity to desire only the good. Even so, he makes space for the necessity the humanity must, on its part, willingly engage that capacity. Thus, Maximus represents well the distinction between automatic universalism and the possibility that all will respond in the end. But listen to how confident he is of said possibility!

God will truly come to be “all in all,” embracing all and giving substance to all in himself, in that no being will have any more a movement independent of God, and no being will be deprived of God’s presence. Thanks to this presence, we shall be, and shall be called, gods and children, body and limbs, because we shall be restored to the perfection of God’s project.[9]

If Maximus was not a universalist, then he is a perfect example of the hopeful inclusivism to which I subscribe, and he definitely permits me to hope.

In fact, to those who would want Orthodox theologians to refrain from teaching hope or even to refrain from teaching precisely what these Fathers taught, as they taught it—I am pleased to simply teach that they taught it and that they permit me to hope.

The Ancient Liturgies Permit Me to Hope

While the theology of individual Fathers is their own, the liturgy of the Church is ours collectively and stands for something enduring (or why bother with it). It functions not only to give us words of worship, but also theological instruction.

Within the liturgy, we have a great many verses about Christ’s victory over death and hades, especially those referring to the rescue of those in the depths of the afterlife netherworld. Those who want to be precise like to distinguish hades from hell (gehenna), reserving the former for the place of the dead prior to Easter and the latter for the state of those in eternal torment after the Final Judgment. In the interim, between Holy Saturday and the Day of the Lord, the two words tend to get conflated. And that conflation has typically broadened to a general identification such that hades and hell are used almost synonymously.

We cannot entirely dismiss this conflation as sloppy semantics by English translators. In fact, hades and gehenna at times seem virtually interchangeable in Second Temple Judaism, into the first century and perhaps the New Testament.[10] I am beginning to see the wisdom of that move when it comes to the all-encompassing victory of Christ. The only function of a sharp distinction is to limit Jesus Christ’s saving power to the narrower era and smaller cosmology of hades, while the conflation makes Christ the Conqueror of every terrace and crevice of hell!

With that preface, rejoice with this reader in the first of two of my favorite liturgical passages:

- From the Oktiochos/Tone 2[11]

The Great Doxology and after it the Resurrection Troparion

Having risen from the tomb, and having burst the bonds of hades, * Thou hast destroyed the sentence of death, O Lord, * delivering all from the snares of the enemy. * Manifesting Thyself to Thine apostles, Thou didst send them forth to preach; * and through them hast granted Thy peace to the world, * O Thou Who alone art plenteous in mercy.

Typika and Beatitudes

We bring unto Thee the prayer of the Thief, and we cry: Remember us, O Saviour, in Thy Kingdom.

We bring unto Thee, for the pardon of our offences, the Cross, which Thou didst accept for our sake, O lover of mankind.

We worship Thy burial and Thy Rising, O Master, through which Thou didst redeem the world from corruption, O Lover of mankind.

By Thy death, O Lord, death hath been swallowed up, and by Thy Resurrection, O Saviour, Thou hast saved the world.

Those who slept in darkness, O Christ, seeing Thee the Light in the lowest depths of Hades, did arise.

On rising from the grave Thou didst meet the Myrrh-bearers and ordered them to tell Thy Disciples of Thine Arising.

Let us all now glorify the Father, worship the Son and praise with faith the Holy Spirit.

Rejoice throne formed of fire; Rejoice Thou Bride without bridegroom; Rejoice O Virgin who hath born God for mankind!

Resurrection Troparion Tone 2:

When Thou didst descend unto death, O Life Immortal, * then didst Thou slay Hades with the lightning of Thy Godhead. * And when Thou didst also raise the dead out of the nethermost depths, * all the Hosts of the heavens cried out: * O Life-giver, Christ our God, glory be to Thee.

Resurrection Kontakion Tone 2:

Thou didst arise from the tomb, * O all-powerful Saviour, * and seeing the marvel Hades was struck with fear, * the dead arose, and creation with Adam seeing this rejoiceth with Thee, * therefore the world doth glorify Thee, my Saviour.

- Paschal Homily

No discussion on eschatological hope in the liturgy can skip St. Chrysostom’s (347-407) Paschal homily. So anointed was this sermon that the Church has chosen to preach it every single Pascha from the time it was composed in the late 300’s until the Lord comes again with glory to judge the living and the dead. It is significant that the harrowing of hades is translated into the English and published on the O.C.A. website (for example) to say that Christ emptied hell. If the distinction between hades and hell were more important theologically than the proclamation of Christ’s total victory, then they should correct the translation. Why don’t they? I suspect that they have retained the language of hell because it best represents Chrysostom’s intent: total victory by the Risen King. Here are the relevant paragraphs that we do preach as doctrine in all Eastern Orthodox Churches around the whole world on the most important feast day of the year:

Enjoy ye all the feast of faith: Receive ye all the riches of loving-kindness. let no one bewail his poverty, for the universal kingdom has been revealed. Let no one weep for his iniquities, for pardon has shown forth from the grave. Let no one fear death, for the Savior’s death has set us free. He that was held prisoner of it has annihilated it. By descending into Hell, He made Hell captive. He embittered it when it tasted of His flesh. And Isaiah, foretelling this, did cry: Hell, said he, was embittered, when it encountered Thee in the lower regions. It was embittered, for it was abolished. It was embittered, for it was mocked. It was embittered, for it was slain. It was embittered, for it was overthrown. It was embittered, for it was fettered in chains. It took a body, and met God face to face. It took earth, and encountered Heaven. It took that which was seen, and fell upon the unseen.

O Death, where is your sting? O Hell, where is your victory? Christ is risen, and you are overthrown. Christ is risen, and the demons are fallen. Christ is risen, and the angels rejoice. Christ is risen, and life reigns. Christ is risen, and not one dead remains in the grave. For Christ, being risen from the dead, is become the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep. To Him be glory and dominion unto ages of ages. Amen.[12]

If hell is overthrown and “not one dead” remains in the grave—if Christ is the first fruits of the resurrection of all who have fallen asleep, then the Paschal homily of St John Silver-tongue permits me to hope and to preach that hope. If I were restricted to preaching the hope described above, I would do so with very great joy.

The Modern Catechisms Permit Me to Hope

But perhaps my interpretation of Scripture, the Fathers and the liturgies is immature and unwarranted. I doubt it; I’ve avoided interpretations in favor of letting them speak for themselves. But when in doubt, no problem. This is why we have the authorized interpretations of formal catechisms. Catechisms, as I understand them, are teaching tools formally approved as Orthodox for use in preparing catechists for baptism.

That said, not all catechisms speak in unison. They reflect their authors, regions and eras like all the other Orthodox sources. Still, when one finds a catechism that resonates, would it be fair to say the catechist can teach what it says? I will mention and quote just two.

- Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev’s The Mystery of Faith[13]

Metropolitan Hilarion’s catechism, The Mystery of Faith (published by St. Vladimir Seminary Press), concludes with these powerful thoughts on judgment, hell and the end:

What is hell? Why Hell? many people ask. Why does God condemn people to eternal damnation? How can the image of God the Judge be reconciled with the New Testament message of God as love? St Isaac the Syrian answers these questions in the following way: there is no person who would be deprived of God’s love, and there is no place which would be devoid of it; everyone who deliberately chooses evil instead of good deprives himself of God’s mercy. The very same Divine love which is a source of bliss and consolation for the righteous in Paradise becomes a source of torment for sinners, as they cannot participate in it and they are outside of it.

… If God is love, He must be full of love even at the moment of the Last Judgment, even when He pronounces His sentence and condemns one to death.

For an Orthodox Christian, notions of Hell and eternal torments are inseparably linked with the mystery that is disclosed in the liturgical services of Holy Week and Easter, the mystery of Christ’s descent into Hell and His liberation of those who were held there under the tyranny of evil and death. The Church teaches that, after His death on the Cross, Christ descended into the abyss in order to annihilate Hell and death, and destroy the horrendous kingdom of the Devil. Just as Christ had sanctified the Jordan, which was filled with human sin, by descending into its waters, by descending into Hell He illumined it entirely with the light of His presence. … This does not mean that in the wake of Christ’s descent into it, Hell no longer exists. It does exist but is already sentenced to death.

And then, under the heading “… A New Heaven and a New Earth,” the catechism comes to its climax with this final paragraph:

Thus, according to St Gregory and to certain other Fathers of the Church, the final outcome of our history is going to be glorious and magnificent. After the resurrection of all and the Last Judgment, everything will be centered around God, and nothing will remain outside Him. The whole cosmos will be changed and transformed, transfigured and illumined. God will be ‘all in all’, and Christ will reign in the souls of the people whom He has redeemed. This is the final victory of good over evil, Christ over Antichrist, light over darkness, Paradise over Hell. This is the final annihilation of death. ‘Then shall come to pass the saying that is written: ‘Death is swallowed up in victory’. ‘O death, where is thy sting? O Hell, where is thy victory?… But thanks be to God, Who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ’ (1 Cor.15:54-57).

Is Metropolitan Hilarion a universalist? In Christ the Conqueror of Hell, he quotes the Great Saturday Matins Canon:

Hell reigns, but not forever, over the race of mortals; for you, O Mighty One, when placed in a tomb, shattered with your Life-giving hand the bars of death, and proclaimed to these who slept there from every age no false redemption, O Saviour, who have become the first-born of the dead. [14]

But he immediately resists easy answers and insists that “the services of Great Saturday raise the curtain of mystery … revealed only in the kingdom to come, in which we will see God as he is and in which God will be ‘all in all.’”[15] Honoring free will, he acknowledges that hell reigns for as long as even one of us respond, “No,” to God … but, the liturgy says, “Not forever.”

Yes, behind Metropolitan Hilarion’s catechism stands vision informed by the liturgy that permits me to hope.

Another catechism that permits hope is the original French version of The Living God. Prior to its translation into English, the French catechism included an article by Fr. Alexandre Turincev, originally written in the 1960’s. His hope is much more fervent than we’ve encountered heretofore. Reflecting on the Paschal homily,

… how must we consider these wildly categorical affirmations of St. John Chrysostom concerning the chaining, humiliation and death of hell – its annihilation? Let us state frankly – the idea of eternal hell and eternal suffering for some and eternal bliss (indifferent to suffering) for others, can no longer remain in the living and renewed Christian conscience as it was formerly presented in our catechisms and our official theology courses. This archaic conception which claims to be based on the Gospel texts, understands them in a literal, coarse and material sense, without penetrating the hidden spiritual meaning of the images and symbols. This conception is increasingly showing itself to be an intolerable violation of Christian conscience, thought and faith. We cannot accept that the sacrifice of Golgotha has revealed itself to be powerless to redeem the world and conquer hell. Otherwise we should say: creation is a failure, and Redemption is also a failure. It is high time for all Christians to witness in common and reveal their mystical experience – intimate in this area – as well as their spiritual expectations, and perhaps also their revolt and horror before materialistic, anthropomorphic representations of hell and the Last Judgment, and of the heavenly Jerusalem. It is high time to be done with all these monstrosities – doctrinal or not – often blasphemous, from ages past, which make of our God of Love that which He is not: an ‘external’ God, who is merely an “allegory of earthly kings and nothing else.” The pedagogy of intimidation and terror is no longer effective. On the contrary, it blocks entry into the Church to many who are seeking a God of Love “who loves mankind” (the “Philanthropos” of the Orthodox liturgy).[18]

Here, Turincev not only permits me to hope, but virtually demands it (and that, many decades ago) … in a published catechism (“doctrinal or not”), no less. Lest we rush ahead, I am inclined to follow a caution—nay, a stern warning—from St Silouan the Athonite that Fr. Turincev felt compelled to embed in his paper. Is there a possibility that some should find themselves “outside” at the last? A holy monk of Mount Athos[19], a staretz who was almost our contemporary, wrote the following, addressed to every Christian: “If the Lord saved you along with the entire multitude of your brethren, and one of the enemies of Christ and the Church remained in the outer darkness, would you not, along with all the others, set yourself to imploring the Lord to save this one unrepentant brother? If you would not beseech Him day and night, then your heart is of iron—but there is no need for iron in paradise.”[20]

Yes, perhaps there are those who should yet fear exclusion from paradise. Not the pagan, the murderer or adulterer, for we find their hearts softening to the woos of the Bridegroom. But the one who perchance ought to fear is that soul who knows they are ‘in’ and someone else is ‘out,’ and insists on dogmatizing their own privileged dualism.

Far better the humility of hope for all that imagines no one in hell but oneself, yet despairs not.

The Symbol of Faith Permits Me to Hope

Finally, a word about the Creed. Does the creed permit me to hope?

Our central dogma and theological lens is the final form of the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381. It boils down that eschatology which Orthodox Christians must confess and restricts the eschatology which may be imposed. In other words, rather than seeing the eschatology of the Creed as constrictive, we ought to regard it as an essential formulation minimizing dogmatism, preserving mystery and protecting freedom of belief.

The Creed limits what we can teach as eschatological dogma to four points:

-

-

- He shall come again in glory,

- To judge the living and the dead,

- We look forward to the resurrection,

- And the life of the age to come.

-

Does the Symbol of Faith permit me to hope?

Yes, in that the coming Judge is the Lord Jesus Christ, the merciful and man-befriending God who loves mankind.

Yes, in that we all face the one Judge, whose judgments are merciful, whose purpose is restoration and whose character is self-giving, radically forgiving love.

Yes, in that everyone shall be raised, every eye shall see him and every knee will bow and every tongue confess that Jesus Christ is Lord to the glory of God the Father.

And yes, in that we look forward to the life of the age to come.

The life of the age to come. There is no dogma about the death of the age to come, the hell of the age to come, or the unending torment of the age to come. Even if there is an eternal hell where the damned are condemned to burn forever and ever, its existence is not acknowledged by the Creed or the Council that composed it as dogma. I do not believe for a moment that this is an accidental omission or oversight for the purpose of brevity. No, this is the strategic hand of Gregory of Nyssa (and probably Gregory the Theologian), wisely protecting in perpetuity the theological freedom of those who would hope as they did.

Yes, the Creed permits me to hope. And to the degree that the Church remains Orthodox—honors the Scriptures, the Fathers, the liturgies and the catechisms—it will always at least permit me to hope as well.

Postscript:

And yet, Andrew Klager reminds me,

… this permission to hope doesn’t and shouldn’t come from other Orthodox Christians anyway; although these discussions and the fine distinctions, nuances, and subtleties in them are important—clumsily putting words to what’s ineffable (and in the future, i.e., that which hasn’t even happened yet)—the permission to hope ultimately comes from partaking of the same divinity that conquered death and emptied hell.

Indeed, from where does the hope itself come? Permission or not,

My hope is built on nothing less

than Jesus blood and righteousness;

I dare not trust the sweetest frame

but wholly lean on Jesus’ name.

On Christ the Solid Rock I’m found;

All other ground is sinking sand,

ALL other ground is sinking sand.

If biblical hope, as one commenter claims, is ‘sure confidence,’ then that blessed Hope is not built from below on human foundations or institutions, not even Scripture or the Church, but was and is given by grace from above, through Love Incarnate, and by the transfiguration of those hearts that behold the Lord whose love is wider, deeper, higher than we could ever ask or imagine.

Glory to God, those who through the mercies of theosis have beheld that vision of Hope cannot un-behold it.

Notes

[1] David Bentley Hart, “Saint Origen,” First Things (Oct. 2015).

[2] For example, Ilaria Ramelli, The Christian Doctrine of Apokatastasis: A Critical Assessment from the New Testament to Eriugena (Brill, 2013); Thomas Allin, Christ Triumphant (Wipf & Stock, 2015); David Burnfield, Patristic Universalism (Universal-Publishers, 2013).

[3] Clement, Stromata, 6.6.46.

[4] Gregory of Nyssa, “When (the Father) Will Subject All Things to (the Son), Then (the Son) Himself Will Be Subjected to Him (the Father) Who Subjects All Things to Him (the Son).”

[5] Ware, “Dare We Hope,” 207. From Homily 27(28): tr. Wensinck, 136; tr. Miller, 141.

[6] Ware, “Dare We Hope,” in The Inner Kingdom, 207.

[7] Ware, “Dare We Hope,” 208. (Isaac, Homily 40.7, tr. Brock, 176).

[8] I am most convinced by Andreas Andreopoulos, “Eschatology in Maximus the Confessor,” The Oxford Handbook of Maximus the Confessor, ed. by Pauline Allen and Bronwen Neil (Oxford University Press, 2015), 322-40.

[9] Maximus the Confessor, Ambigua to Thomas 7,1092C. Cited in Ramelli, Apokatastasis, 739.

[10] Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2009), 11.

[12] St. John Chrysostom, “Paschal Homily.”

[13] An Online Orthodox Catechism: Adopted from Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, The Mystery of Faith.

[14] Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 192.

[15] Alfeyev, Christ the Conqueror of Hell, 193.

[16] Alexandre Turincev, “An Approach to Orthodox Eschatology,” trans. by Brad Jersak et al, The Canadian Journal of Orthodox Christianity 9.1 (Winter 2014): 1-19 and Greek Orthodox Theological Review 58.1-4 (Spring-Winter 2013): 57-77.

[17] Olivier Clément, Dieu est Vivant: catéchisme pour les familles par une équipe de Chrétiens Orthodoxes (Editions du Cerf, 1979), the original French edition of The Living God: A Catechism for the Christian Faith, 2 Vols. Trans. by Olga Dunlop (St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1988).

[18] Turincev, “An Approach to Orthodox Eschatology,” 17.

[19] St Silouan the Athonite (died 1938, canonized 1988).

[20] Turincev, “An Approach to Orthodox Eschatology,” 17.

(7 December 2015)

I was just chrismated into the Orthodox Church this past Sunday and like Dr. Jersak, one of the major reasons why I felt comfortable doing so was because I found within its walls a harbor of hope. I have a been a convinced universalist for at least a few years now and it was important for me to find a church that did not insist on damning most of the world in the name of the Gospel. It was quite a relief to find that not only was I able to find a church that allows for great hope, it turns out that none other than the historic church allows for such hope. Oddly enough though, it was my experience that while fewer people within the evangelical church seemed to allow for the possibility of universalism, it was actually much simpler to be a universalist because there was no authority outside of the bible and my own reasoning. There was no scarcity of people to tell me that I was woefully in error, but nobody dared to throw out the word heresy. I felt as though most theological positions were open to me somewhere under the protestant/evangelical umbrella. Within Orthodoxy, one must be a bit more careful. The language of hope seems proper to me.

LikeLiked by 4 people

congratulations Matthew!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Same here Matthew!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think that Orthodoxy will always be the bastion of the universal hope. But, even for those of us who toil in the Protestant hinterlands, such as this misfit Calvinist, I would only add that the universal hope is for the Church writ large, even if our traditions chafe against it. Part of my motivation for constant contact with the Orthodox community is because the clearest, most compelling voices for universalism are found there, and I hope that this witness will continue to grow beyond the Orthodox communion, and perhaps be a source for deeper unity within the church.

LikeLiked by 5 people

Yes, right. Universal hope is for the whole church because it is the Gospel. There’s no good news evangel without it; the Gospel without hope for all is then only for those who are strong enough to pull themselves up by the spiritual bootstraps.

LikeLiked by 7 people

Thank you Dr. Brad.

LikeLike

I have been a casual reader of this blog for quite some time now. While I am an amateur when it comes to my understanding, knowledge, and practice of theology, eschatology, philosophy, etc., nor am I an Orthodox Christian (I grew up in a Protestant church, in a largely Protestant area), I thoroughly enjoy reading this blog and posts of this nature. Being myself a “hopeful” Universalist in public (but a confessing Universalist in private…), this post truly resonated with me; so I wanted to express my thanks and enjoyment of reading it.

It’s tough being constantly exposed to and surrounded by Protestant Christians being a hopeful Universalist because it makes you feel alone and, rather frustratingly, feel like a heretic. But, know that reading this blog, and posts like this, has been one of the most encouraging things for me lately. So, know that this blog helps us non-Orthodox laypeople too.

Thank you and God bless,

LikeLiked by 5 people

I am too a hopeful Universalist, i think in a way i always have been. My father in law call me a heretic and thinks i have lost my way for believing that all will be eventually reconciled.

If i Calvanism is really true, that makes me suicidal to think of the horror of that.

I have read a few of Brad Jersak’s books, they are very encouraging and really well researched, he makes a strong case for being a hopeful Universalist.

You are in good company, i understand your frustration.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Reforming Hell.

LikeLike