by Roberto De La Noval

In the psalm traditionally ascribed to King David and set in the aftermath of his adultery with Bathsheba and the murder of Uriah, we hear David cry to God in confession: “Against you, you only, have I sinned and done what is evil in your sight” (Ps 51:4). We naturally ask how this confession makes sense—if David has slept with a man’s wife and then killed that man in order to cover it up, how can David have sinned only against God? Clearly he has sinned against, at least, two others, and that is not even counting the child who would die as the result of David and Bathsheba’s illicit union. Interpreters have answered this question variously, though perhaps the most popular reply is that all sin is directed towards God insofar as we dishonor God by disobeying His commandments or by hurting the creatures which belong to Him.

This response is no doubt accurate as far as it goes, but we would be remiss to leave the question at that. I mean that the psalm, if read in the context traditionally given to it in King David’s life, should worry us. Where is the justice for the good man dead, for the woman who was likely taken against her will and then left husbandless, for the child who suffered for David’s sins? And where is the repentance towards them? To move so quickly to the sin against God may seem premature, especially for those who know that God demands we be reconciled with our neighbor before we bring our gift to the altar.

But David’s cry can be read otherwise, and perhaps even in spite of his intentions. For there is a deep rumbling in his words, the beginnings of a tectonic shift in how we conceive of our relationship towards God and towards our neighbor. That earthquake is the same one that shook Jerusalem one good Friday when a mob and a corrupt imperial figurehead conspired to put an innocent man to death. Few were able to see the injustice of that event, though many saw its outward form and movement. But the good man who died that day pleaded on the behalf of his murderers at the moment of death, praying: “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

That man was, and is, the Son of God, the eternal Word of the Father who took flesh for us humans and for our salvation, Jesus Christ. He knew that the only confession possible for those who were putting him to death would have been David’s, “against You only have I sinned.” But they were ignorant, like David, like all of us. It is only in the bruised and bloodied face of Jesus that we discover the great secret of the psalm: to sin against our neighbor is, in the most real way, to sin against God.

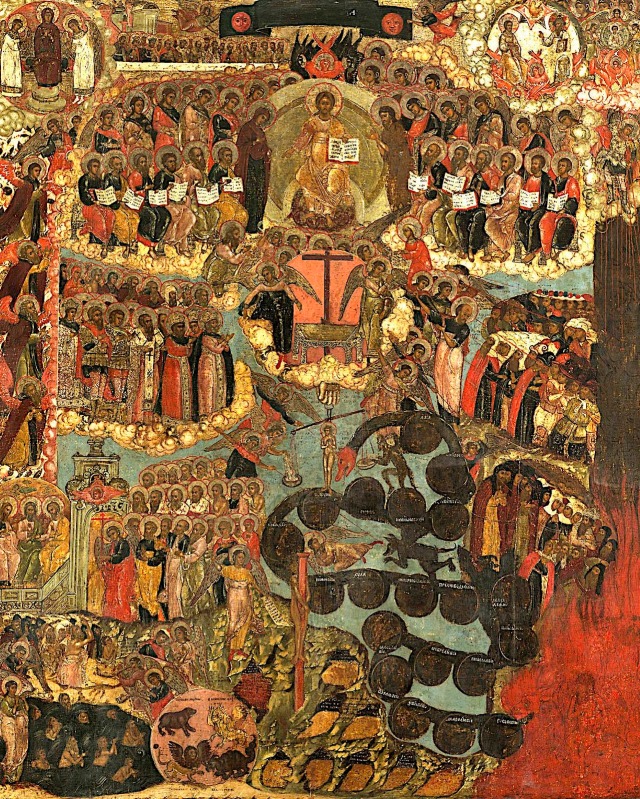

If this language seems too strong, recall Jesus’ eschatological discourse in Matthew 25. There Jesus teaches us how God will judge the world:

When the Son of Man comes in his glory, and all the angels with him, then he will sit on the throne of his glory. All the nations will be gathered before him, and he will separate people one from another as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats, and he will put the sheep at his right hand and the goats at the left. Then the king will say to those at his right hand, ‘Come, you that are blessed by my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world; for I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me something to drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me, I was naked and you gave me clothing, I was sick and you took care of me, I was in prison and you visited me.’ Then the righteous will answer him, ‘Lord, when was it that we saw you hungry and gave you food, or thirsty and gave you something to drink? And when was it that we saw you a stranger and welcomed you, or naked and gave you clothing? And when was it that we saw you sick or in prison and visited you?’ And the king will answer them, ‘Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these who are members of my family, you did it to me.'”

“You did it to me.” Jesus identifies himself then, now, and eschatologically with the broken of the world. In this lies the significance of the fact that it is the Son of Man who judges the world at the end of days, as Jesus tells us. The final judgment is God’s, but it is humanity’s judgment too, for God is none other than this man. Indeed, in the logic of our Christian faith, it is God’s judgment only because it is humanity’s judgment. This is the meaning of Jesus’ statement that the Father has given to the Son to judge because he is the son of man. This is the divine-human cryptogram of the incarnation.

Why should judgment belong to the Son because he is the son of man? Because Jesus, as John tells us, ‘knew what was in man.’ But he knew as well what it was to be man, and to be man is to exist under judgment. Or at least it is so for the weakest of this world, those who are rejected, despised, and ill-used, the ‘scum of the earth,’ as St. Paul puts it. These are the ones who languish in prison, who go hungry and naked, who wander from nation to nation looking for a home. Their life is one constant, unjust judgment. And so God chose not to judge the world from without; He elected instead to judge it from within. This is why He came, why He took flesh—to sit under the false judgment of the world and to be crushed beneath it. “By a perversion of justice he was taken away; who could imagine his future?”

Still, just as we asked why David should repent towards God and not towards his victims, we may ask anew why it is that this man can judge the world. Very well that he identifies with us, but why should our sorrows, the wrongs we have borne, become grist for his judgment? Here we arrive at the mystery of Jesus’ eschatological verdict, a revelation that is simultaneously the secret of David’s cry: “You have done it to me,” in Matthew 25 means nothing other than “Against You only have I sinned.” This God, this Man, is invested with the authority of final judgment because He is, in some way we know not how, us.

If Christ can be mystically present in his saints, then it is no difficulty to imagine that He is also mystically present in all of humanity, though this is a truth deeply obscured from us. It is the cause of the recurring motif of ignorance we find in the New Testament when it comes to judgment. Paul’s judgment, “If they had known, they would not have crucified the Lord of Glory,” is a particular instantiation of the broader truth that sinners “know not what they do.” To oppress God’s images is to oppress the God in whose image they are made, for He is not far from His people.

Let me not be misunderstood: there remains and will never be overcome the distinction between the hypostatic presence of the eternal Word as Jesus of Nazareth and the mystical presence of God in us all. But this distinction cannot create a chasm between us and our Creator, for in Him we live, and move, and have our being. Even more, it is not as if the enfleshment of Christ was an afterthought or a contingency plan in the life of the Trinity. The Lamb was slain before the foundation of the world, Scripture tells us, and while this cannot be read as an eternal positing of a fallen creation that would require God’s death (for in Him is no darkness at all), it nonetheless must be understood as an affirmation of the eternal humanity of God. Such is the teaching of Maximus Confessor, who saw in the diverse logoi of creation the one Logos. and so too Fr. Sergius Bulgakov taught in his doctrine of the correlation of created and Divine Sophia. While God is always God beyond us, He eternally wills to be God with us.

“Sacrifice and offerings you have not desired, but a body you prepared for me.” In the Trinitarian venture of creation, as Hans urs Von Balthasar describes it, the Father, Son, and Spirit bring forth creatures so as to make a gift of us to each other. And so this body for the Son began to be prepared from the very first day of Genesis. This means we can hear in those concluding words of the creation story, “And God saw that it was very good,” the same words Christ spoke over creation before He passed over from this world to God: “This is my body.” Fruit of the God’s earth and work of human hands, Christ holds the host in his hands as he holds the world in being. We are that body, prepared for generations until He took his abode in Mary Ever-Virgin and from her received his proper human flesh. If we do not worry of speaking of the Church as Christ’s body, neither should we balk at saying that all the broken flesh of the world is also His. For God did not make a new body for Christ in a moment of radical new creation—the veneration of the Mother of God and the Holy Ancestors of Christ precludes such a thought. Instead, the doctrine of the Virgin Birth secures Christ’s family relation to the entire human race: He has made of one blood all the nations of men for to dwell on the earth. Such is the mysticism of biblical genealogy.

All this to say that we fall far short of glimpsing the awesome scope of God’s love for us if we imagine that Christ only externally identifies with the downtrodden at the eschatological tribunal. Rather, Christ is the downtrodden at that tribunal, both in his proper flesh as Jesus of Nazareth to which he remains hypostatically united for the ages, and as his broader human body as well. “It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me.” This is a reality for those baptized who have received the gift of Pentecost, but it is latent in all made in the image of God’s image, the Son who is the same yesterday, today, and forever. And for those who cooperate with God in their journey of becoming Christ, not only in their poverty and powerlessness but also in their freedom and self-determination, the eschatological judgment of Christ will include them in their agency. We are told that we will judge even angels. When we do so, it will be as Christ only because we are in Christ. God will be all in all.

Does all this speculative theology tell us anything about the content of that final judgment from Christ’s lips? In the discourse of Matthew 25 we hear that some will end up on Jesus’ right hand and others on his left, all depending on how they ministered to God in the flesh. One frightening—and consoling—realization follows from this. If Christ will judge us depending how we have cared for the weak among us, then we can only conclude that we are currently undergoing God’s eschatological judgment. This is the other half of the ‘realized eschatology’ that is so often invoked to explain the presence of God among us and the benefits we receive through Christ’s Spirit. But we should also attend to the darker realities of the eschatological life. St. Paul himself tells us that we are living in the era of the resurrection of the dead. Christ has been raised as the first fruits, and this means the eschaton has begun. “We are those upon whom the ends of the ages have come.” “The hour is coming, and now is, when the dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live.” St. John’s Gospel explains this dynamic even more explicitly: the Son of God came into the world not to judge it, but to save it. That said, his very presence is the judgment of the world, for those who love darkness hide from the light that enlightens every person—past, present, and future—who comes into the world. And that presence remains on earth, not only in his body in the Church, but also in every suffering and broken reflection of Christ suspended on the cross.

And so we meet our Judge in our day-to-day life. How often we fail Him—against Him only have I sinned! But we are also given grace to minister to Him, to thank Him for his humility in emptying Himself to dwell with us in the flesh, and to work out our salvation with the Spirit working within us, so that we may hear words of good cheer on the final day: “Well done, good and faithful servant.”

We are graced beyond measure to have had the veil lifted and to see the hidden causes of the eschaton before us. But what of those who do not know, those who operate in ignorance—what of their fate? Matthew 25 is rarely read with its plain meaning, for in that statement on the sheep and the goats Jesus explicitly says that those who end up on Jesus’ right hand are not aware that it is Jesus to whom they are ministering. The same goes for the goats on the left. It is Jesus Himself who tells us that many will enter the kingdom who do not know what it is they are doing other than the fact that they are doing good. They have loved justice and mercy, and so they have unwittingly walked humbly with their God.

Many, however, expect a full welcome on the last day and will be surprised to hear they are not invited. This time Jesus is the one who expresses ignorance: “I never knew you; depart from me.” Presumably they never knew Him either, though they thought they did. And then there are the rest, who are just as ignorant of the identity of the Christ they persecute when they oppress those with the name of Christ or when they leave a needy child without a cup of cold water. St. Paul was such a one, and he writes that though he was once “a blasphemer, and a persecutor, and a violent man, I was shown mercy because I acted in ignorance and unbelief.” In this, Paul’s confession of his past life, we catch the echo of Jesus’ own words in his final moments, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do,” and in hearing these words we find hope. Though it is not given to us to know the end from the beginning, we do know that Christ is both end and beginning, alpha and omega, and we know that if we have seen him we have seen the Father who has handed all judgment over to him.

Christ has spoken that the goats will go out to the fire prepared for the devil and his angels, and we know that is a sure word. Yet we also ask with Abraham, “Will not the judge of the earth do right,” the judge who was judged on the earth and who asked for forgiveness for his killers anyway? “In the crucified Christ we recognize,” as Jürgen Moltmann wrote, “the Judge of the final Judgment, who himself has become the one condemned, for the accused, in their stead and for their benefit. So at the Last Judgment we expect on the Judgment seat the One who was crucified for the reconciliation of the world, and no other judge”

And so we have great reason to hope that the content of the final judgment will be identical to that uttered on Good Friday: “Father, forgive them.” That forgiveness is not opposed to the banishment into darkness, for as George MacDonald preached, our God is a consuming fire, and the darkness of those eschatological flames must burn away our ignorance, rebellion, and self-will until the fire becomes recognizable to us as God. But we can say more. As theologian John Thiel illuminates in his book “Icons of Hope,” the forgiveness of sins and the life of the age to come are syntactically connected in the Creed, and this suggest a further thematic proximity between them. If we are mystically Christ, both potentially in our creation and pneumatically in our regeneration, then we must expect that the eschaton will be a time when we find Christ’s words of forgiveness on our lips as well. Only in this way can God justly judge the world, when He judges with us, and when we judge with His judgment—for we shall judge angels. We will forgive our debtors as we have had our debts forgiven by the incarnate Son of God. Those who have sinned against us and against God we will forgive, and we will all stand before Christ as Christ, members of His body, the totus Christus offered to the Father whose very name is mercy. We will say to Him as we say to each other, “Against you only have I sinned,” and He will forgive us, and we will weep with the tears that water the trees for the healing of the nations.

* * *

Rob De La Noval is a doctoral candidate in theology at the University of Notre Dame. His research focuses on Sergius Bulgakov and Russian Religious Thought. He has also translated multiple works by Bulgakov, with one forthcoming in the Journal of Orthodox Christian Studies and another (with co-translator Yury P. Avvakumov) in process with University of Notre Dame Press. He has published with Public Orthodoxy, America Magazine, and Church Life Journal, among others.

Thanks again, Rob, for sharing this thoughtful reflection with the readers of Eclectic Orthodoxy.

LikeLike

Bulgakov and Balthasar are reliable guides. This is an insightful reflection. I would add a further suggestion that the vocation of man is to speak for all of creation. The little ones and the neglected are inclusive of the beasts and the lillies of the field. When one focuses on the totus Christus consider that it is as head of creation that we bear all the theophoric names, whispering the eschatological secret of every sparrow with child-like wonder.

LikeLike