Andrew Hronich believes that purgatorial universalism is the “most biblically sound and philosophically coherent” species of universalism.1 He also believes that it is properly identified as a subspecies of escapism, “a genus spawning universalist, traditionalist, and conditionalists variants.”2 Over the past two decades, Andrei A. Buckareff and Allen Plug [B&P] have been the most prominent exponents of escapism. Two claims characterize the model:

- Hell exists and might be populated for eternity.

- If there are any denizens of hell, then at any time they have the ability to accept God’s grace and leave hell and enter heaven.3

In their writings on this topic, B&P assume the issuant construal of damnation as articulated by Jonathan Kvanvig. “An adequate conception of hell must be an issuant conception of it,” explains Kvanvig, “one that portrays hell as flowing from the same divine character from which heaven flows. Any other view wreaks havoc on the integrity of God’s character.”4 God’s love is his principal motivational feature. He desires the salvation of all and offers forgiveness to all. The issuant conception therefore implies the rejection of retributive presentations of perdition as contrary to the defining attribute of the Creator. Interminable punishment cannot be reconciled with the divine love and mercy. The purpose of hell is not to punish its inhabitants but to accommodate their rejection of communion with the Creator. This estrangement may entail suffering but if so only of a privative nature. In freely choosing hell, the damned suffer the loss of the benefits and goods that heaven offers:

The fundamental good lacking in hell is the heavenly community, in which eternal bliss is found in union with God and with others freed from the imperfections of the human condition. This suggestion yields a privative picture of the pain of hell, for it accounts for the evil of hell in terms of what it lacks compared to heaven. In this view, those in hell are exiled from heaven 5

But whereas Kvanvig believes that hell is everlasting (short of metaphysical suicide), B&P contend that in his infinite love God grants the damned infinite opportunities to repent and enter into the bliss of heaven; at any point they may choose to accept God’s forgiveness and escape their infernal condition. A God of absolute love, they maintain, will not arbitrarily close-off the possibility of reconciliation with the rational creatures he has created. Hronich elaborates:

God’s desire for a restored union with His estranged children ought to be reflected in His policies enacted in the eschaton. If a closed-door policy is enforced in the eschaton, then God’s soteriological policies would be entirely disharmonious with His current policies on this side of the eschaton. For God’s policies to remain constant towards His creatures, He would, like the parent of an estranged child, ever seek the avenue by which to restore communion with His estranged children. The possibility of escape from hell must therefore always remain a live option for hell’s denizens. In other words, escapism must be true.6

B&P do not contend that all will be saved, nor do they exclude the possibility that all will choose everlasting perdition. They simply posit the following: in his abundant love and mercy, God will persistently and unrelentingly offer the gift of reconciliation to the damned. B&P’s position approximates the afterlife world imagined by C. S. Lewis in The Great Divorce. Readers will recall that in the story a bus line runs between heaven and the grey town. The inhabitants of the latter are always free to hop on the bus and go on holiday in heaven. When they arrive, they are met by friends and family who show them around and encourage them to remain and enjoy the happiness of Trinitarian communion. Even so, most choose to return to the dreariness of the grey town. Given human freedom, that is the best love can do—invite and beseech. The gates of hell may be locked from the inside, but God isn’t going to coerce anyone to turn the key and walk through them. If the wicked definitively choose to exclude themselves from the fellowship of divine charity, well, that’s their business. There’s nothing more to be done but wish them well:

If we accept that God’s being just and loving follows from His moral perfection, then we should expect that God would make provisions for people to convert in the eschaton. Moreover, the opportunities for people to convert should not be exhausted by one post-mortem opportunity. We will call this view of hell ‘escapism’. Escapism is compatible with the hope that the vast majority of, and perhaps all, created persons will finally be saved. On the other hand, escapism does not commit us to holding that anyone who does or will inhabit hell will ever be reconciled with God. So escapism is compatible with a species of hopeful or weak universalism, and it is compatible with the view that no one in hell will be saved.7

But what does it mean to say that one is able to leave hell? B&P are not just saying that it is logically possible for one of the lost to accept God’s grace and enter into communion with him; they are also claiming that it is psychologically possible for them to do so. This may seem like a distinction without a difference, but it is crucial to the escapist proposal. Recall that the purpose of the issuant model is to provide a justification for hell independent of retributive considerations. God has bestowed upon his rational creatures the freedom to choose an eternal existence with him or apart from him.8 In choosing the latter, the damned have freely accepted the privation of the goods of communion. They, and they alone, are responsible for their infernal condition; there is no one else to blame—so the argument goes. But B&P also claim that the lost souls possess the freedom to reconsider their decision and change their minds. Perhaps they overestimated the value of an independent existence. Perhaps they misjudged the existential consequences. Perhaps the accommodations aren’t up to their expectations. Hence the escape provision: “Here’s your ticket. Take the bus to heaven and stay there forever. We guarantee you won’t be disappointed. Not only is there no greater and more loving God, but there is no greater and more wonderful place than the heaven he has created for us. Everyone in heaven experiences boundless joy and inconceivable ecstasy. No one suffers from buyer’s remorse!”

The post-mortem offer of new life is predicated on the freedom to assent to the offer. But if one or more of the lost souls are so imprisoned within their sin and narcissism that they are psychologically incapable of availing themselves of it, then the offer is nothing more than a sham. Yes, it may be logically possible for them to accept grace and enter into joy—all they have to do is do it—but if they are so deeply addicted to their vices and disordered passions that they are constitutionally incapable of accepting the offer, then God’s promise of future happiness is bogus. It’s analogous to a predestinarian Calvinist telling his congregation, “Christ died for you. Believe on him and you will be saved,” all the while believing and knowing that the gospel is intended only for the elect: the reprobate will always be incapable of genuine faith and repentance. A sincere offer implies the freedom to accept the offer. That the damned possess the libertarian freedom to receive the grace of reconciliation, we might say, is an implied stipulation of the escapist proposal. Curiously, B&P equivocate on this stipulation (see below).

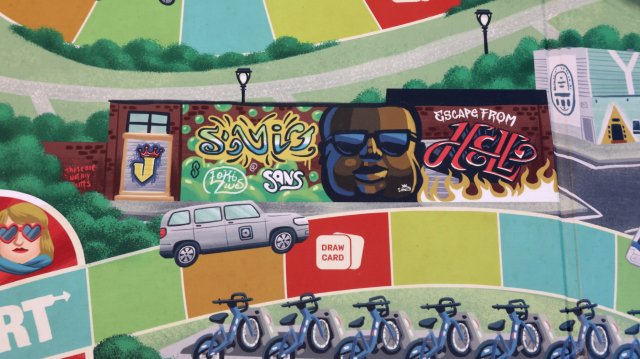

Once the possibility of escape from hell is introduced, we find ourselves with a naming problem. Are the damned in hell or in purgatory? What nouns should we use? In The Great Divorce, the narrator has a conversation with his guide precisely on this point:

“But I don’t understand. Is judgement not final? Is there really a way out of Hell into Heaven?”

“It depends on the way ye’re using the words. If they leave that grey town behind it will not have been Hell. To any that leaves it, it is Purgatory. And perhaps ye had better not call this country Heaven. Not Deep Heaven, ye understand.” (Here he smiled at me.) “Ye can call it the Valley of the Shadow of Life. And yet to those who stay here it will have been Heaven from the first. And ye can call those sad streets in the town yonder the Valley of the Shadow of Death: but to those who remain there they will have been Hell even from the beginning.”9

Where does heaven begin and hell end? I cannot refrain from citing the famous poem composed by Sir Percival Blakeney, Bt.10

Back to divine matters. Benjamin Matheson believes he has identified two flaws in the escapist proposal. First, if divine respect for human freedom mandates that God should maintain an open-door policy between heaven and hell, then the same logic would seem to require that the blessed should also have the opportunity to take the bus to Gehenna:

God is morally perfect, and so all-loving and just. As God is all-loving and just, he will always be open to persons accepting his gracious offer of life-everlasting in communion with him in Heaven. Hence, God will ensure that those in Hell are always free to leave. The analogous argument for escapism about Heaven is as follows: God is morally perfect, and so all-loving and just. As God is all-loving and just, he will always be open to persons rejecting his gracious offer of life-everlasting in communion with him in Heaven. Hence, God will ensure that those in Heaven are always free to leave. This argument can be further reinforced by appealing the parent analogy that Buckareff and Plug use to support their argument for escapism. They claim that God is like a loving parent who is always open to her children returning, even if they had a falling out. In the same way, a loving parent will not force her children to stay at home (if they are capable of looking after themselves, of course)—that it is to say, a loving parent will allow her children the freedom to leave home whenever they choose. Thus, God should also keep the doors of Heaven open.11

In other words, the blessed must have the same libertarian freedom as the damned. If the latter have the ability to choose otherwise, so must the former. Just so, God will graciously honor the choices of both the damned and the blessed. Lacking this symmetry, contends Matheson, B&P’s escapism falls into incoherence. Yet does it? Why is it contradictory to affirm both the escapability from hell and the nonescapability from heaven? Perhaps the two situations are disanalogous. Perhaps commitment to a lesser or apparent good (characteristic of the miserific vision) is not identical to embrace of the infinite Good (characteristic of the beatific vision). In any case, Matheson does not provide a compelling explanation for the necessary symmetry between the freedom of the damned and the freedom of the saints. I score ten points for team Escapism.

Matheson continues his disputation by pointing out that heavenly bliss rules out the possibility that any of the blessed would ever want to leave heaven. After all, being in heaven, a place than which none greater can be conceived, means being in communion with a being than which none greater can be conceived, and this communion entails enjoying happiness than which none greater can be conceived and experienced. “How could anyone ever imagine,” asks Matheson, “let alone consider, leaving such a place?”12 But if no one ever leaves heaven, if no one can leave heaven, then that would suggest that B&P are invoking two different notions of freedom. Matheson does not explicitly say this, but that is how I interpret his confusing concern about symmetry. Departure from hell entails libertarian freedom; departure from heaven, either source or compatibilist freedom. Escapism is therefore incoherent.

In their response to Matheson, B&P formulate his central argument as follows:

- If, according to escapism, there is no symmetry with respect to God’s policies towards those in both heaven and hell, then escapism is not an adequate response to the problem of hell.

- On escapism, there is no such symmetry.

- Therefore, escapism is not an adequate response to the problem of hell.13

B&P agree with premise #2 but reject #1. They begin by clarifying what it means for someone to choose heaven. It is not like choosing to go on holiday to Paris or the Italian Riviera. “The assumption in the Abrahamic religions,” they write, “is that one is intending to enter into deep communion with the divine. One must have the sort of character that allows one to identify such a state as heavenly.”14 Fellowship with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit requires one to become the kind of person for whom the communion of love is sheer heaven. “Nothing short of either an immediate and radical person-transforming change upon entering heaven or a fair amount of time in purgatory developing a taste for the divine project by completing the process of sanctification or theosis can bring about the change needed in an agent to be fit for heaven.”15

B&P, therefore, do not see a problem with the asymmetry between the damned and the blessed. The asymmetry is unavoidable given the radical differences between hell and heaven. Unlike the reprobate, the saints are eternally and inalterably established in their love and enjoyment of God—this is an inevitable and necessary consequence of seeing the divine essence. It’s not that God decides not to adopt an open road policy for the blessed. No such policy is necessary, given heavenly union with the transcendent Good. If the saints in heaven could, per impossible, turn away from God, that would simply indicate that they had not known him in the fullness of his glory.

Yet there remains Matheson’s second challenge: the problem of personal incorrigibility. According to defenders of the doctrine of eternal perdition, the reprobate are irredeemably settled in their rejection of communion with God; they are frozen in their ungodliness and therefore incapable of repentance. In Roman Catholic theology, this is the difference between the souls in hell and the souls in purgatory. The escapist proposal requires the elision of this difference. B&P acknowledge that their doctrine of hell muddies the waters. “It may be true,” they remark, “that the doctrine of hell being defended is purgatorial in a very loose sense,” . . . but it does not “fulfil the purposes that purgatory has traditionally been taken to serve.”16

Matheson criticizes Buckareff and Plug for not providing cogent reasons to justify their claim that the damned possess the freedom to escape hell if they so desire. The criticism is spot on. The escapist proposal fails if the damned do not possess genuine libertarian freedom. In their words: “If there are any denizens of hell, then at any time they have the ability to accept God’s grace and leave hell and enter heaven” (emphasis mine). Moreover, B&P undermine their case by conceding that some of the damned may have acquired a fixed character during their earthly lives, thus rendering them impervious to divine influence: “Admittedly, it is possible that an agent’s character may become settled after a while. If so, the agent may find it psychologically impossible properly to respond to God’s prevenient grace.”17 And in response to Matheson’s article, they expressly refuse to affirm his claim that the open door policy requires God to provide the damned with the ability to leave hell, presumably because they believe that a unilateral action of this kind would violate personal autonomy. In making this concession, B&P have effectively admitted that God has abandoned all the departed souls (if any) who have acquired a settled anti-God orientation, thus bringing the unconditionality of God’s love into question:

It only takes one person to never have the option to leave Hell to cast doubt on the claim that God is all-loving and just. After all, the escapist’s thesis is motivated by the claim that because of God’s loving nature he wants all persons to join him in Heaven. But if the open-door policy is restricted, then God would not be all-loving, as this would entail that he’s given up on certain persons. . . . However, if God has not provided each person in Hell with the freedom (or ability) to leave Hell whilst in Hell, then he has effectively given up on them. God might offer grace to such persons in Hell in the same way that someone endlessly offers Joe an iced tea. If the person knows that Joe hates iced tea and that he’ll never actually accept this ‘offer’, then this person isn’t really offering Joe an iced [tea]. I take it that a genuine offer is one that the recipient is actually able to accept. Since God is all-loving, the open-door policy cannot be restricted. This means that God should ensure everyone in Hell has the freedom or ability to leave.18

B&P’s response to Batheson on this question is disappointing. Briefly put: given the complexities of the human psyche, we cannot make firm judgments about the immutability of post-mortem character:

It strains credulity to confidently maintain that any human agent can develop the sort of settled character in the span of a normal human lifetime that would make her post-mortem state such that she is permanently psychologically incapable of responding to divine prevenient grace and the offer of reconciliation.19

But surely it depends on whose credulity is being strained! Psychologists tell us that psychopaths cannot be cured; they are fixed in their psychological state. Short of a divine miracle, why believe that a psychopath who hates God in this life will stop hating him in the next? Similarly, why believe that someone who has cultivated a malevolent spirit will eventually succumb to the post-mortem wiles of the God of love? How many SOBs who dramatically convert to Christ remain SOBs in the years and decades afterwards? Conversions are a dime a dozen, but genuine moral and spiritual transformations are rare. So what are the odds of God successfully converting Adolf Hitler, Josef Stalin, and Pol Pot (to name just three of the usual suspects)? A more robust understanding of divine grace is needed. Score 10 points for team Matheson.

Am I being unfair to Messrs Buckareff and Plug? If so, I ask their forgiveness. But despite their sympathy for the greater hope, they have adopted a vulnerable middle position: maybe all will be saved; maybe all will be damned—there’s no way for any of us to know. Yet still they opine that a proper understanding of divine love and justice requires an open door policy. If B&P had presented their escapism as a thought experiment, conceding upfront that they have no idea whether those in hell possess the libertarian freedom to repent, then I would have nothing to protest. Yet they chose instead to advance a puzzling, perhaps incoherent, middle of the road position that can neither be preached as gospel nor taught as a possible development of doctrine. I am reminded of Robert Frost’s words: “The middle of the road is where the white line is—and that’s the worst place to drive.”

Addendum

In my first article on Once Loved Always Loved, I noted that I was surprised by the number of typos and errata. I can now report that these kinds of errors run through the entire book. Here is an example of one of the most egregious—a six-step syllogism ostensibly proposed by Morgan Luck:

- God is the greatest conceivable being.

- If God is the greatest conceivable being and world A is better than world B, then God does not actualize world B.

- A world where 5 is true is better than a world where 10 is true.

- So, God does not actualize a world where 10 is true.

- If God does not actualize a world where 10 is true then 10 is false.

- So, 10 is false.20

When I read this, it didn’t make sense to me. To what do 5 and 10 refer? I had no idea. Perhaps, I thought, they refer to propositions previously stated. So I went back to the beginning of the section titled “Escapism” and reread (and reread) the pages preceding the above syllogism. I found a four-step syllogism attributed to Matheson:

- God is the greatest conceivable being.

- If God is the great[est] conceivable being then God communes with people in the greatest conceivable place.

- God communes with people in heaven.

- Heaven is the greatest conceivable place.21

Hmm. No 5 or 10. Hronich immediately comments on Matheson’s argument:

The purpose of Matheson’s syllogism is to demonstrate the incompatibility of premise 4 and the proposition, “Everyone in hell can leave.” If it is psychologically impossible for people to leave heaven, then the same should be true of hell. “[I]f Heaven is the greatest conceivable place, then how can anyone leave it? It seems that if heaven is that great, then once a person has experienced it, she is not going to be able to want to leave.” Matheson’s argument is riddled with errors.22

This doesn’t look promising, but stay with me. One page later the author brings Luck into the discussion. Here’s the money passage:

Furthermore, premise 4 also seems false. Matheson’s central claim is that the propositions 5 (“Everyone in hell can leave”) and 10 (“Heaven is the great[est] conceivable place”) cannot both be true because if everyone in hell can leave, then everyone in heaven can also leave; in which case heaven is not the greatest conceivable place. Likewise, if heaven is the great[est] conceivable place, then no one in heaven can leave; in which case no one in hell can leave. Thus, for Matheson, there is no possible world in which propositions 5 and 10 are true.23

I confess that when I first read this passage, I did not notice the assignment of the numbers 5 and 10 to the two propositions. Clearly I wasn’t paying as close attention as I should have. Let’s plug in the propositions and see what we get:

- God is the greatest conceivable being.

- If God is the greatest conceivable being and world A is better than world B, then God does not actualize world B.

- A world where “Everyone in hell can leave” is true is better than a world where “Heaven is the greatest conceivable place” is true.

- So, God does not actualize a world where “Heaven is the greatest conceivable place” is true.

- If God does not actualize a world where “Heaven is the greatest conceivable place” is true then “Heaven is the great conceivable place” is false.

- So, “Heaven is the great conceivable place” is false.

To be honest, this syllogism now makes less sense to me than the original. That tells me that I’ve probably made a mistake. As my critical ego is always telling me, “You’re a fool, dolt, and nincompoop.” Perhaps there are possible worlds where Hronich’s six-step syllogism is comprehensible. In my real world, however, I can’t make heads or tails out of it. And if I can’t understand the syllogism, then that probably means that most ordinary readers won’t understand it either. If I am missing something obvious, please tell me.

Having come this far, there was only one thing left to do: figure out how 5 and 10 got attached to the specific propositions. So I then read Morgan Luck’s article “Escaping Heaven and Hell.” Bingo! Propositions 5 and 10 are identical to premises 5 and 10 in her 29-step syllogism (yes, 29 steps!). The exasperating puzzle of 5 and 10 has been solved! Needless to say, one shouldn’t have to hunt down Luck’s article through ILL in order to understand Hronich’s syllogism.

I do not know who is to blame. Author? editor? proof-reader? All I know is that somebody should have noticed the problem before the book went to press.

Footnotes

[1] Andrew Hronich, Once Loved Always Loved (2023), 273.

[2] Ibid. I am not yet convinced that the doctrine of universal salvation qualifies as a species of escapism, but I ain’t going to quibble.

[3] Ibid., 274.

[4] Jonathan Kvanvig, The Problem of Hell, 136. See “Hell: Prison or Nothingness?”

[5] Kvanvig., 137.

[6] Hronich, 274. “So if God longs for reunion with us this side of the eschaton, then it would be arbitrary and out of character for God to cut off any opportunity for reconciliation and forgiveness at the time of death. Moreover, if God’s policies remain constant towards us, and if we are the object of God’s parental love, then God must be like any other parent, who never ceases to desire to have her estranged child return, be forgiven, and enjoy the blessings of communion with the parent. This requires that the opportunities for receiving the gift of salvation must extend beyond a single post-mortem opportunity. Rather, the possibility of escape from hell must always be there for the residents of hell. So escapism must be true. And, if escapism is true, then God never gives up on the unsaved after death. The only thing that would block their access to communion with God would be their failure to make the right decision in response to the Holy Spirit’s prevenient grace. So we should not expect God to give up on the unsaved and block the door to reconciliation. . . . Leaving an opening for the recalcitrant to turn to and enjoy communion with God seems like a reasonable policy for a just and loving Creator and parent to adopt. So escapism should be the view of hell adopted by Christians.” Andrei A. Buckareff and Allen Plug, “Escaping Hell: Divine Motivation and the Problem of Hell,” Religious Studies 41 (2005): 44-45, 46.

[7] Buckareff and Plug, 41.

[8] B&P do not define freedom, but they appear to be committed to libertarian (the power to do otherwise) or source incompatibilism (actions originate in the agent). This will become important when we address the question of heavenly freedom.

[9] C. S. Lewis, The Great Divorce (1945), chap. 9.

[10] For the sake of posterity but apropos to nothing, I share this poem written by James Ray Cottrell for my ordination to the Diaconate in June 1980:

He seeks one here. He seeks one there.

He seeks a parish everywhere.

Is he from heaven? Is he from hell?

The sinecure-seeking the Reverend Kimel.

[11] Matheson, 200.

[12] Ibid., 201.

[13] Andrei A. Buckareff and Allen Plug, “Escaping Hell But Not Heaven,” International Journal for Philosophy of Religion, 77 (2015): 247-253. I only have access to the online version of the article, which lacks the pagination of the published version.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Buckareff & Plug, “Escaping Hell,” 49.

[17] Buckareff & Plug, “Escaping Hell,” 54 n. 21. The quote continues: “But even supposing someone’s character becomes settled, it does not follow that God ever gives up on her. We believe that the most consistent policy for God to maintain would be to continue to offer reconciliation to such a person. In such an instance, it at least remains metaphysically possible for such an agent to repent and leave Hell.” Quite honestly, I have no idea what B&P mean when they say that God never gives up on those who are psychologically incapable of responding to his grace in faith and repentance. They have given every indication that they are Arminian in their understanding of divine grace (viz., it’s resistible). If this is true, then God is incapable of unilaterally restoring to the damned the libertarian freedom they have lost—at least not without violating their personal autonomy. Are we to imagine the transcendent Creator as sitting in the stands rooting on the damned to do something he knows they cannot and will not do?

[18] Matheson, 205.

[19] Buckareff & Plug, “Not Heaven.”

[20] Hronich, 277.

[21] Ibid., 275.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Ibid., 276-277.

re “God has bestowed upon his rational creatures the freedom to choose an eternal existence with him or apart from him.”

That doesn’t sound perfectly rational.

All of these tortuous defenses of hell by Hronich, Kvanvig, Stump et stumble out of the logical starting gate with incoherent conceptions of what it means to be perfectly free & rational.

Also, I’m married to the idea of our being impeccable in purgatory.

LikeLiked by 2 people

yup, they are perfectly confused about the nature of freedom!

LikeLiked by 1 person

“psychopaths cannot be cured”

I’m sorry, but this line of thought completely rejects the sovereign power of God. Is anything impossible for God? Does God create things that are inherently broken and irredeemable from the very start? How could we say they even had the option to choose then? Such designates them as vessels of divine wrath just as surely as any Calvinist teaching.

They did not ask to be created. They did not ask to be placed into a gauntlet of pain, suffering, temptation, and lies, then told (possibly) that they must find the one true path or forever be damned. How is their creation then not just as much a violation of their free will as forcing them to accept God?

If there are any that cannot be saved, then God is a failure. If they were created inherently incapable, then God failed in their creation. If they became so at some point in their life, then God failed both by creating the cosmos that such a possibility could come about, as well as by “missing” them before they reached such a point. To think that he who created time would run out of it is absurd.

Such line of thinking removes God’s active will that seeks us even while we are his enemies, that seeks the lost sheep, that heals not because we asked for it, but because some friends lowered us through the roof. Look at the life of Hitler and you will see a broken man. Listen to the words of Martin Luther against the Jews and you will hear the hatefulness that was taught to Adolf.

If none else shall pray for his salvation then I will. For the first ten thousand years of eternity I will do nothing but pray for the very worst of humankind that no one else will. As vile as their crimes, they were not formed in a void, they were a symptom of a greater sickness—one that we are all responsible for.

God can save and God will save, because such is his will and nothing is impossible for El-Shaddai.

LikeLike

Shaun, you must be new to my blog; otherwise, you would know that I am a firm universalist and therefore believe that God can save anyone and will save everyone. Given that, go back and reread the offending sentences and figure out why I wrote what I wrote. 😀

LikeLiked by 1 person

I know well that you are and I understand that you were presenting the opposing argument, but I don’t see the point of offering it as having any merit at all when in truth it has none. It is just as twisted and contradictory to the character of God as all infernalist arguments.

LikeLike

notwithstanding the misunderstanding as noted by Fr. the middle paragraphs of your comment are a wonderful defense of the One who is. it was stirring to read in spite of the misunderstanding that birthed the comment. well done. peace.

LikeLike

Hello Robert. How do you understand the nature of freedom? For me, I think anyone with a perfectly holy and good will would never reject God´s love in Christ. The problem is, I don´t think anyone has such a will this side of eternity. That said, I think after death God continues working for the good of even those who rejected him in this earthly life … helping their wills to be conformed to God´s will.

LikeLike

Hi Matthew,

It can be summarized along these lines: to be perfectly free and rational is to desire the Good. To choose not the Good is to not have known it, and to not have known it is to be less than free. So when it is stated that, “God has bestowed upon his rational creatures the freedom to choose an eternal existence with him or apart from him” this is incoherent nonsense, for to choose an existence (eternal or otherwise) apart from God is neither rational nor free.

I hope that somewhat explains. There are several great posts here on the subject of freedom, see here for instance.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Robert. So would you say that God wills all people to be perfectly free and rational and that God won´t stop until all of creation desires the Good?

LikeLike

And if no one has such a will (holy and good that is), then it can only be by grace that any of us come to accept God´s love and forgiveness in Christ.

LikeLike

Yes for sure – and our very existence is by grace

Universalist really lean into the grace part of things – but on the other hand the notion of synergy is also very key, when we speak of freedom I cannot come up with another position that does true and full justice to creaturely freedom.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I don’t think you were unfair to B&P. Quite the opposite.

The two main claims that characterize ‘escapism’ (as you describe their view):

1. Hell exists and might be populated for eternity.

2. If there are any denizens of hell, then at any time they have the ability to accept God’s grace and leave hell and enter heaven.

I don’t see how both claims can be true. If the 2nd is true, then movement toward God as final end is always possible and this precludes the possibility that anyone will ever, per the 1st claim, succeed at having spent “eternity” in hell. However long one suffers hell, one never traverses the distance to achieve eternity. All it can mean is that one is always in a position to prolong one’s suffering. But if one is also in a position to turn to God, then the notion that hell “might be populated for eternity” is meaningless. I know some will want to fabricate an abstract possibility here and insist that we imagine something real when we imagine perpetually choosing to reject God ‘for all eternity’, but no real possibility is being imagined here (not for those who grant the 2nd claim above).

Good point about the asymmetry to. I agree the choice between God and hell (or self, or the world) cannot be symmetrical, for the simple reason that God has no proportional contradictory end. That’s not to say that in our penultimate state (gnomic choice, epistemic distance, etc) there isn’t a certain symmetry between choices contemplated – “God or ___” (fill in the blank). But that’s not to say what B&P are saying, which is the stronger claim that metaphysically speaking the alternatives of such a choice must present ‘proportional consequences’, i.e., must be proportional in the effects which each choice secures. But this is false. I’m a libertarian regarding choice, but even I realize this notion of proportionality is nonsense.

It’s about teleology, and only God can be creation’s final end. Choice is formation, habituation, solidification of nature and character. We all know this to be true. But even here the tendency to habituate has to be understood within the constraints of nature understood teleologically as given and sustained by God. One is always free to come to rest irrevocably in one’s ‘natural’ end (God). But it doesn’t follow from this that one must also be free to come to rest irrevocably in some false end, i.e., in misrelation to, or denial of, God as one’s final end. I think it is creation ex nihilo that establishes this asymmetry, teleologically speaking, and defines absolutely the scope of what is truly ‘possible’ for creatures.

LikeLiked by 1 person