“The Lord comes in glory with all the holy angels and with the saints, with all that is holy on earth and heaven. But where is She,” asks Sergius Bulgakov, “the Most Pure and Most Beloved One, raised into heaven in her Dormition and sitting ‘at the right hand of the Son’?” (The Bride of the Lamb, p. 409).

Where will be the Most Blessed Virgin Mary when her Son returns in glory? This is not a question a Protestant Christian would ever think to ask; but it is one that comes naturally to Orthodox and Roman Catholic Christians as they meditate on the Second Coming of Christ. Holy Scripture does not address the death and eternal destiny of the Blessed Virgin, yet both communions confess Mary as already enjoying a glorified existence. The mystery has been long kept in the inner heart of the Church. The Orthodox Church annually celebrates the Dormition of the Theotokos on August 15th:

Glorious are thy mysteries, O pure Lady. Thou wast made the Throne of the Most High, and today thou art translated from earth to heaven. Thy glory is full of majesty, shining with grace in divine brightness. O ye virgins, ascend on high with the Mother of the King. Hail, thou who art full of grace: the Lord is with thee, granting the world through thee great mercy. (Stichera)

I shall open my mouth and the Spirit will inspire it, and I shall utter the words of my song to the Queen and Mother: I shall be seen radiantly keeping feast and joyfully praising her Dormition. O ye young virgins, raise now with Miriam the Prophetess the song of departure. For the Virgin, the only Theotokos, is taken to her appointed dwelling-place in heaven. The heavenly mansions of God fittingly received thee, O most holy, who art a living Heaven. Joyously adorned as a Bride without spot, thou standest beside our King and God. (Canticle One)

Neither the tomb nor death had power over the Theotokos, who is ever watchful in her prayers and in whose intercession lies unfailing hope. For as the Mother of Life she has been transported into life by Him who dwelt within her ever-virgin womb. (Kontakion)

As the tomb of her Son is empty, so is the tomb of his Mother. Having endured the suffering and death that is the curse of fallen humanity, Mary is raised to incorruptible life by the Savior and exalted as Queen of Heaven, the first fruits of the New Creation inaugurated in the resurrection of Christ:

The Mother of God in her resurrected and glorified body is already the completed glory of the world and its resurrection. With the resurrection and ascension of the Mother of God the world is completed in its creation, the goal of the world is attained, “wisdom is justified in her children,” for the Mother of God is already that glorified world which is divinized and open for the reception of Divinity. Mary is the heart of the world and the spiritual focus of all humanity, of every creature. She is already the perfectly and absolutely divinized creature, the one who begets God, who bears God, and receives God. She, a human and a creature, sits in the heavens with her Son, who is seated at the right hand of the Father. She is the Queen of Heaven and Earth, or, more briefly, the Heavenly Queen. (Bulgakov, The Burning Bush, pp. 74-75)

In the Blessed Virgin Mary, raised to the right hand of her Son, deified creaturehood is perfectly achieved and manifested. And so the Orthodox Church acclaims her “more honorable than the Cherubim, and beyond compare more glorious than the Seraphim.”

Bulgakov fittingly describes the Theotokos as the image of the Holy Spirit. Unlike the eternal Son, the Holy Spirit does not have have his own hypostatic manifestation; he does not incarnate himself as a human being. He is revealed in his activities and gifts. Supremely he is revealed in the saints who have surrendered their lives to God and thus become transparent to divinity:

A personal incarnation, a hominization of the Third Hypostasis, does not exist. Still, if there is no personal incarnation of the Third Hypostasis, no hominization in the same sense in which the Son of God became human, there can all the same be such a human, creaturely hypostasis, such a being which is the vessel of the fulfilment of the Holy Spirit. It completely surrenders its human hypostatic life, makes it transparent for the Holy Spirit, by bearing witness about itself: behold the handmaid of the Lord. Such a being, the Most Holy Virgin, is not a personal incarnation of the Holy Spirit, but she becomes His personal, animate receptacle, an absolutely spirit-born creature, the Pneumatophoric Human. For, if there is no hypostatic spirit-incarnation, there can be a hypostatic pneumatophoricity, by which the creaturely hypostasis in its creatureliness completely surrenders itself and as it were dissolves in the Holy Spirit. In this complete penetration by Him it becomes a different nature for its own self, i.e., divinized, a creature thoroughly blessed by grace, a “quickened ark of God,” a living “consecrated temple.” Such a pneumatophoric person radically differs from the Godman, for it is a creature, but it differs just as much from a creature in its creatureliness, for it has been elevated and made a partaker of divine life. (pp. 81-82)

The Orthodox veneration of the Theotokos cannot be sufficiently explained by Mary’s physical birthing of Jesus nor even by her decisive fiat, “May it be done to me according to your word.” It can only be explained by the perfection of her humility and holiness and her supreme embodiment of theosis. I find it surprising, therefore, that Bulgakov’s presentation of the Theotokos should have attracted severe Orthodox critique. St John Maximovitch, for example, associates Bulgakov with the Mariological excesses of Roman Catholicism and accuses him of virtually incorporating Mary into the Godhead, of making her “an Intermediary between men and God, like Christ.” But Bulgakov clearly distinguishes the Theotokos from the Holy Trinity. She is not divine, except in the sense in which St Athanasius speaks of theosis: “God became Man so that man might become God.” This is a deification by grace, not by nature. Bulgakov explains the critical difference:

As a creature, she does not participate in the divine life of the Most Holy Trinity according to nature, as does her Son; she only partakes of it by the grace of divinization. But this grace is given to her already in a maximum and definitive degree, so that by its power she is the Heavenly Queen. (p. 76)

For the divine hypostasis of the Logos divine nature is His proper nature, and the human nature is appropriated and assumed by Him from Mary “for our sake and on account of our salvation”; for the human hypostasis of Mary her proper nature is human nature, and divine life is communicated to her by the grace of divinization, in keeping with the visitation of the Holy Spirit. Therefore in no manner can the Mother of God be venerated as the Godman. But her pneumatophoricity, which makes her an animate temple of God and the Mother of God, elevates her higher than human nature and higher even than any creaturely nature. Mary the pneumatophoric human is more exalted than any creature and thus “every creature, the angelic choir and the human race, rejoices” on account of the Graced One. (pp. 88-89)

What is this but theosis? St Gregory Palamas speaks of deification in Christ as becoming “uncreated by grace,” and in his Homily on the Dormition he declares: “She only is the frontier between created and uncreated nature, and there is no man that shall come to God except he be truly illumined through her, that Lamp truly radiant with divinity, even as the Prophet says, ‘God is in the midst of her, she shall not be shaken’ [Ps. 45:5].”

Of all the saints in heaven, the Mother of God alone enjoys the fullness of eschatological existence, for she alone has been bodily raised from the dead. All others, including St John the Baptist, await the reunion of body and soul in the general resurrection. The theological significance of Mary’s translation is evidenced in the way the Church invokes her intercession. “Between her and all the saints,” Bulgakov explains, “no matter how exalted, angels or men, there remains an impenetrable border, for to none of them does the Church cry out save us, but only pray to God for us. With respect to the whole human race she is already found on the other side of resurrection and last judgement; neither the one nor the other has any force for her. … She is the already glorified creation before its general resurrection and glorification; she is the already accomplished Kingdom of Glory, while the world still remains ‘in the kingdom of grace'” (pp. 76-77; also see Vladimir Lossky, “Panagia“).

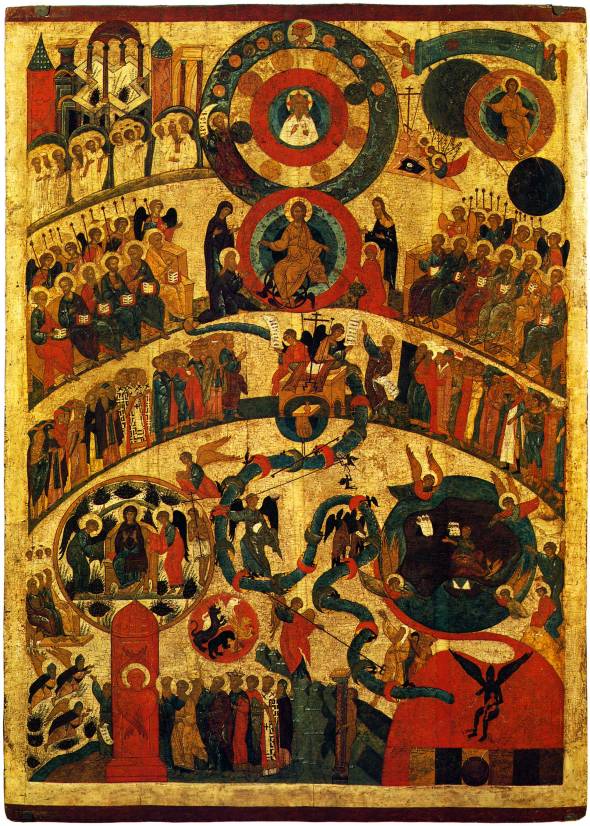

And so we come back to opening question: Where will the Theotokos be found at the parousia? The answer is given in the icons of the Last Judgment: she will be standing at the right hand of her Son, invoking the divine mercy upon sinful humanity. She herself will not be judged, for she already lives beyond judgment; nor will she judge, for that prerogative belongs to God alone. “She will come into the world; She will come into the world with Her Son in His glory, in the parousia. For the parousia of the Son is also necessarily the parousia of the Mother of God, for it is She, who is the creaturely glory of the world, the glory of Christ’s humanity. She is His hypostatic humanity. She is the Spirit-Bearer, the living gates for the parousia of the Holy Spirit, through which the Holy Spirit comes onto the world.” (Bride, pp. 409-410).

Where else would the Blessed Virgin be when Satan is cast out and the world is remade in a twinkling? And so Bulgakov boldly suggests that the final words of the New Testament speak also of her:

And let the Spirit and the Bride say, Come.

And let him that heareth say, Come!

Even so, come, Lord Jesus!

Most Holy Theotokos, save us!

[9 July 2014; mildly edited]

I love the cantor in the video you posted.

LikeLike

“This is not a question a Protestant Christian would ever think to ask” – I can’t remember ever seeing it so posed, but ‘never say never’: it is always interesting to (try to) find more about what various 16th-century Reformers (and their heirs down the centuries) thought about the Blessed Virgin Mary. A quick Wikipedia browse yields, from Bullinger’s De origine erroris libri duo (On the Origin of Error, Two Books) (1539), “Hac causa credimus ut Deiparae virginis Mariae purissimum thalamum et spiritus sancti templum, hoc est, sacrosanctum corpus ejus deportatum esse ab angelis in coelum” (‘For this reason, we believe that the Virgin Mary, Begetter of God, the most pure bed and temple of the Holy Spirit, that is, her most holy body, was carried to heaven by angels’) (“Assumption of Mary” article as of “20 July 2016, at 19:35”).

I like Bulgakov’s thought that “there can be a hypostatic pneumatophoricity,” but the expression “by which the creaturely hypostasis in its creatureliness […] as it were dissolves in the Holy Spirit” seems worse than unfortunate.

LikeLike

Bulgakov seems to have lots of expressions that are worse than unfortunate. 🙂

LikeLike

This sounds suspiciously like the Mother of God as Mediatrix of all Grace:

“What is this but theosis? St Gregory Palamas speaks of deification in Christ as becoming “uncreated by grace,” and in his Homily on the Dormition he declares: “She only is the frontier between created and uncreated nature, and there is no man that shall come to God except he be truly illumined through her, that Lamp truly radiant with divinity, even as the Prophet says, ‘God is in the midst of her, she shall not be shaken’ [Ps. 45:5].””

LikeLike