“Does God Desire All Men to be Saved?” The title pretty much tells us what chapter three of Once Loved Always Loved is about and for whom it is written. Do you need a hint? Our author, Andrew Hronich, was once a committed five point Calvinist, confessing the five doctrinal affirmations formulated by the Synod of Dort in 1618-1619:

- Total depravity

- Unconditional election

- Limited atonement

- Irresistible grace

- Perseverance of the saints

These five points (TULIP) are often seen as the purest form of Calvinism, but as scholars have pointed out, many Calvinists have not affirmed limited atonement, advocating instead a position termed hypothetical universalism. Oliver Crisp offers a succinct description:

Christ offers himself for all humanity with respect to the sufficiency of his work but for the elect alone with regard to its efficacy, because he brought about salvation only for the predestined.1

Hence we may speak of five point Calvinism and four point Calvinism. Hronich focuses his critical attention on the former, and does not mention the latter. I wouldn’t think much if anything hangs on this, but I would have liked to have read his thoughts on hypothetical universalism.

The Dortian five points cannot be discussed without at least mentioning the views against which they were formulated to refute, summarized in the five articles of the 1610 Remonstrance:

- Conditional election

- Universal efficacy of Christ’s atonement

- Total depravity

- Resistibility of grace

- Conditional preservation of the saints

These five doctrinal affirmations characterize the tradition known as Arminianism.2 While the Calvinist–Arminian debate is not relevant to this book review, we may note that all universalists are “Arminian” on one decisive point: the universal efficacy of Christ’s atoning work—hence the significance of the title of this chapter.

When God calls a five point Calvinist into the greater hope, I suspect that the doctrine of limited atonement will almost always be the initial battle ground. Why? Because limited atonement is clearly the weakest plank in the Calvinist position, requiring gross misinterpretation of Scripture, rejection of the consensual view of the Church Fathers on the universal extent of the atonement, and suppression of conscience. Most importantly, it denies the catholic Christian vision of the Holy Trinity as absolute love.3

If I believe anything it is this: the absolute, infinite, and unconditional love of the Holy Trinity, revealed in the life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ, embraces all mankind, without exception. And because it is true and perfect love, it intends the salvation of every person. God wills our ultimate good; and that ultimate good is nothing less than eternal communion in the divine life of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Dortian claim, therefore, that Christ died only for the elect and not for the entirety of humanity can only be anathematized in the clearest and most direct terms. If true, there would be no gospel to proclaim.

Because of my dogmatic rejection of classical Calvinism, I was almost tempted to skip this chapter, assuming that it would be of little interest to me. And to a large extent that is true. But I decided to read on because I knew that it must be personally important to Hronich and was curious to discover which arguments he finds most cogent. It is no easy matter to reject a religious and theological confession to which one was once wholeheartedly committed; even harder is to abandon the community that lives, prays, and teaches that confession.

Does God desire all men to be saved? The Calvinist utters a decided no to the question. The no is mandated by unconditional election: the Father eternally and unconditionally elects those specific individuals whom he wills to save. If God desired the salvation of all, he would have willed the salvation of all; but he only wills the salvation of some. For this reason, the fathers of Dort reasoned that the atoning death of Christ is divinely intended only for the elect:

For this was the sovereign counsel, and most gracious will and purpose of God the Father, that the quickening and saving efficacy of the most precious death of His Son should extend to all the elect, for bestowing upon them alone the gift of justifying faith, thereby to bring them infallibly to salvation: that is, it was the will of God, that Christ by the blood of the cross, whereby He confirmed the new covenant, should effectually redeem out of every people, tribe, nation, and language, all those, and those only, who were from eternity chosen to salvation and given to Him by the Father.4

What, after all, would be the point in saying that Jesus died for all when he only wills the salvation of the elect? That seems confusing. Moreover, if Christ’s death on the cross is a sufficient sacrifice for the sins of all, then this would seem to logically imply that all will be saved, but all Calvinists would disagree with that conclusion. Needless to say, Reformed theologians have spent much ink reflecting on these matters.

A vitally important question immediately rises: If God’s salvific will is restricted to the elect, and if Christ’s work of atonement is efficacious only for them, is it meaningful to say that God loves everyone? The 17th century English Calvinist John Owen did not think so:

We deny that all mankind are the object of that love of God which moved him to send his Son to die; God having ‘made some for the day of evil’ (Prov. 16:4); ‘hated them before they were born‘ (Rom. 9:11, 13); ‘before of old ordained them to condemnation’ (Jude 4); being ‘fitted to destruction’ (Rom. 9:22); ‘made to be taken and destroyed’ (II Pet. 2:12); ‘appointed to wrath’ (I Thess. 5:9); to ‘go to their own place’ (Acts 1:25).5

Is love still love if it does not will the ultimate and final good of the beloved?

Perhaps this sounds too abstract. Let’s make it practical. You are a 5 point Calvinist evangelist hoping to convert to Christ a group of unbaptized unbelievers. Would you be speaking truthfully if you were to say to them: “God loves you, each of you, all of you. He loves you so much he died on the cross for you!”? I think the answer is no. At best you are speaking equivocally. You know that you do not intend “love” to mean “God wills your ultimate good,” but your hearers don’t know that, so perhaps you are technically not guilty of false advertising. Even so, your statement is misleading. Quoting David L. Allen, Hronich utters his protest: “How can God be said to love someone in the gospel offer when he has not provided a means for their salvation via an atonement?”6

Hronich shares the following anecdote to illustrate the confusion and pastoral damage equivocity can cause:

Imagine you have a child whom you entrust to me at my camp, and at the camp, all the children come down with a fatal disease. Fortunately, I manage to obtain enough medical pills to restore all the children to full health. Yet, I only administer the pills to a small number of my campers, while withholding the additional pills from the rest of the campers. All the while, I sit at the bedsides of those campers from whom I have withheld the medicine that would have cured them and speak words of “kindness” and “encouragement” over them, telling them that I will remain at their side, and that I’m here for them! What would be your reaction if you discovered that I had given the pills to other children but not your own? What would you think of me? Would you care to listen to me babble on about how I really loved your son, how I stayed up long nights next to his bedside comforting him? Would you consider this love?7

Does anything change if the Calvinist is a hypothetical universalist who believes that on the cross Jesus offered a full, perfect, and sufficient sacrifice, oblation, and satisfaction for the sins of the world? Probably not. Yes, he is able to truthfully proclaim: “Jesus died for your sins. Believe on him and you will be saved.” But there is more to the story. If the Calvinist were to be completely honest, he would also have to confess to his auditors that that he does not know if any of them have been elected go glory, and if they haven’t, then God will not be providing them the grace to respond in faith to his offer of salvation. To put it in the simplest terms, the Calvinist should tell his audience that he does not know if God really and truly loves them. Perhaps he does, perhaps not. Jerry Walls and Joseph Dongell state the dilemma in which all Calvinists find themselves:

Consider the love of God displayed in offering the gospel to the non-elect—persons who God knows can’t will to accept the offer without the very electing love he has chosen to withhold from them. Apart from electing love, the offer of the gospel only serves as an occasion for condemnation, since sinners who aren’t elect will inevitably reject it and thereby add to their record of disobedience. All of this makes it painfully clear that the non-elect are not loved in the only way that can promote their ultimate well-being. God has not chosen to give them the only thing that can possibly provide true flourishing and fulfillment. . . .

In short, [the Calvinist] should frankly admit to the unconverted that he doesn’t know whether or not God loves them in the crucial sense that is absolutely necessary for them to experience eternal joy and flourishing. God may only love them in the sense that he provides them with earthly benefits and in the sense that he makes them an offer that in their fallen condition they can’t begin to appreciate. When God’s love to the world is reduced to this, it is difficult to see how it can be relished as the astounding good news Christians believe it is.8

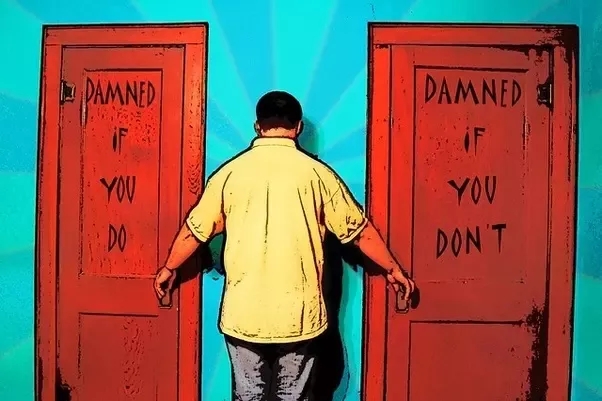

The problem lies with particular predestination. If God elects some but not all to salvation in his Kingdom, then a terrible doubt is introduced into the gospel itself. Neither preacher nor auditor can know whether the good news of Jesus Christ truly intends them. You’re damned if you do; damned if you don’t.

But what if Calvinists should become convinced of the universal intent of God’s love? If this should happen, they will find themselves trapped in the Calvinist Conundrum:

- God truly loves all persons.

- Truly to love someone is to desire their well-being and to promote their true flourishing as much as you properly can.

- The well-being and true flourishing of all persons is to be found in a right relationship with God, a saving relationship in which we love and obey him.

- God could determine all persons freely to accept a right relationship with himself and be saved.

- Therefore, all will be saved.

Hronich quotes the American Calvinist B. B. Warfield to similar effect. If only the Scriptures were not clear on eternal damnation, Calvinists could easily embrace the greater hope, all the while maintaining their fundamental convictions:

So far as the principles of sovereignty and particularism are concerned, there is no reason why a Calvinist might not be a universalist in the most express meaning of that term, holding that each and every human soul shall be saved; and in point of fact some Calvinists (forgetful of the Scripture here) have been universalists in this most express meaning of the term.9

“I thus beseech the better counsel of my Reformed brothers and sisters,” Hronich writes, “and hold out apokatastasis as the complement of Reformed doctrine, maintaining all the essential elements, whilst staying true to the gospel.”10

Footnotes

[1] Oliver Crisp, Deviant Calvinism (2014), 177.

[2] See Roger Olson, Arminian Theology (2006), 30-39.

[3] “If we are true to the New Testament we must assert that the Father loves all his creatures, Christ died for all, but none can come to the Father except the Spirit draw him. But to say it is a ‘mystery’ does not mean we abandon any attempt to probe this mystery, and see what light the Bible and the revelation of God in Jesus Christ throw on the mystery. Theology is faith seeking understanding. What kind of ‘logic’ controls any answers we seek to give? It is a mistake, I believe, to interpret the relation between the headship of Christ over all as Mediator, and the effectual calling of the Spirit in terms of an Aristotelian dichotomy between ‘actuality’ and ‘possibility’. . . It is precisely this kind of Aristotelian logic which led the later Calvinists like John Owen to formulate the doctrine of a ‘limited atonement’. The argument is that if Christ died for all men, and all are not saved, then Christ died in vain—and a priori, because God always infallibly achieves his purposes, this is unthinkable. Where does this same argument lead us when we apply it to the doctrine of God, as John Owen and Jonathan Edwards did? On these grounds they argued that justice is the essential attribute of God, but his love is arbitrary. In his classical defence of the doctrine of a limited atonement, The Death of Death in the Death of Christ, in Book IV John Owen examines the many texts in which the word ‘all’ appears, saying that Christ died ‘for all’, and argues that ‘all’ means ‘all the elect’. For example, when he turns to John 3:16, he says ‘By the “world”, we understand the elect of God only . . .’ What then about ‘God so loved . . .’? Owen argues that if God loves all, and all are not saved, then he loves them in vain. Therefore he does not love all! If he did, this would imply imperfection in God. ‘Nothing that includes any imperfection is to be assigned to Almighty God’. In terms of this ‘logic’ he argues love is not God’s nature. There is no ‘natural affection and propensity in God to the good of his creatures’. ‘By love is meant an act of his will (where we conceive his love to be seated . . . )’. God’s love is thus assigned to his will to save the elect only. It seems to me that this is a flagrant case where a kind of logic leads us to run in the face of the plain teaching of the Bible that God is Agape (pure love) in his innermost being, as Father, Son and Holy Spirit and what he is in his innermost being, he is in all his works and ways.” James B. Torrance, “The Incarnation and ‘Limited Atonement’,” The Evangelical Quarterly, 55 (1983): 84-85.

[4] Canons of Dort II.13.

[5] John Owen, The Death of Death in the Death of Christ, II.4.227.

[6] David L. Allen, The Extent of the Atonement (2016), 779; quoted by Andrew Hronich, Once Loved Always Loved (2023), 102. Yet as Allen describes at length, hypothetical universalists appeal to the universal efficacy of the cross as the ground for proclaiming the gospel to all sinners.

[7] Hronich, 98.

[8] Jerry L. Walls and Joseph R. Dongell, Why I Am Not a Calvinist (2004), 191.

[9] Quoted by Hronich, 323.

[10] Ibid, 129.

It seems to me that it would be a simple matter for a 5-point Calvinist to remain a 5-point Calvinist while embracing apokatastasis:

He would simply affirm that, in the pre-eternal counsels of God, He determined to save each individual person as an individual person. Voila.

This hypothetical Calvinist could explain that God does not save the great mass of mankind, in which each man is an anonymous unit. No. Instead, God saves and calls each man by name. He saves Robert, and Thomas, and William, and Susan, and Lynette, and so on. It is God’s good pleasure to elect each individual man whom He has created.

The doctrine of “limited atonement” in this construal would be a safeguard against thinking of the atonement as an action directed towards an impersonal, undifferentiated mass of anonymous entities.

(And the Calvinist, along with everyone else, need not pretend that the exegetical case for infernalism is stronger than that for universalism.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interestingly, I believe that’s the position that Jacques Ellul advocated.

LikeLike